Is China Changing the Game in Trans-Polar Shipping?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 18 Issue: 7

By:

For more than a decade, Russian policymakers have fruitlessly tried to turn the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which connects Asia and Europe along Russia’s northern coastline, into a viable commercial shipping route (Jamestown Eurasian Daily Monitor, April 29, 2016). PRC financial muscle might finally be able to make their long-sought dream a reality. The idea has appeal for Chinese shipping companies, since it would cut between 1,370 and 4,600 kilometers off the trip between ports in China and Western Europe (CASS, February 28), theoretically saving both time and money by bypassing the Suez Canal. It also has appeal for Chinese policymakers; opening the NSR could secure access to natural resources and ease China’s “Malacca dilemma” (China Brief, April 12, 2006).

Treacherous Sailing

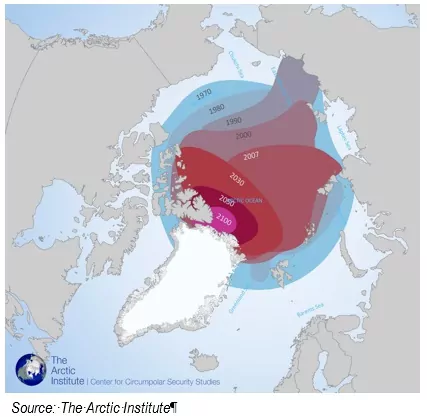

At the moment the NSR is passable by normal cargo ships for only a few weeks each year, and transit speeds are lower than the Suez route because of ice in the water (Finnish Transport Agency, March 9). If global CO2 emissions continue to rise at current rates, however, the “majority of the Arctic Ocean is expected to be open water for half the year” by the end of this century, according to a 2017 report by the UK Government Office for Science. A decrease in the extent of sea ice would vastly increase the usefulness of the NSR (see figure 1).

But the simple presence of open water does not a shipping route make, especially in the treacherous Arctic Ocean. Writing in Jamestown’s Eurasia Daily Monitor in 2016, Dr. Vladislav Inozemtsev was scathing about the route’s present economic viability:

There are no repair or fueling facilities suitable for modern ocean vessels anywhere along the entire route. Moreover, the icebreakers now in use are able to produce a 25-meter-wide ice-free passage, which means the NSR cannot be used by either Suezmax or Panamax container ships [which are nearly 50 meters wide] … To make it appealing to the world’s largest shipping companies, the Russian leadership will need to invest tens of billions of dollars in [a new generation of icebreakers] and local infrastructure upgrades. But to do this, transit tariffs will have to skyrocket, thus leaving the southern route [through the Suez Canal] as the best possible option for shippers. The NSR can function as an economical transit route only if foreign shippers are subsidized by the Russian government, which cannot be the case.

To all this must be added the fact that insurance rates are much higher for vessels operating in polar waters, and specially trained crews are needed to cope with the extreme conditions (UK Office for Science, July 2017). Shallow seabed at key points along the Russian coast also limits the size of ships that can pass (The Arctic Institute, November 2013).

China’s entry onto the scene could be a game-changer. Where Russia lacks the political will and financial muscle to make the scheme commercially viable, the PRC may have the deep pockets, and the economic and strategic rationales needed to see things through to completion.

A “Polar Silk Road”

In a July 2017 meeting with Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping declared Russia and China should “develop their cooperation on arctic shipping routes, jointly building a ‘silk road on ice’” (People’s Daily, January 28). The PRC’s policymaking apparatus has responded to this signal from its top leader: China’s State Council issued the country’s first “Arctic White Paper” in January; PRC media coverage of the ice silk road has been positive and extensive; ministerial working groups from both countries are negotiating the outlines of potential cooperation; and PRC think tanks have been set to work expounding upon the potential benefits of the project.

The PRC analyses produced so far tend to frame new shipping routes as the most important outcome of Sino-Russian polar cooperation, followed closely by the potential for new natural resource extraction (CASS, February 28). They also mention the possibility that NSR shipping could help revitalize China’s economically moribund northeast provinces. Geographically these provinces are much better positioned to take advantage of the shorter routes to Europe the NSR could provide, since the time difference between the NSR and the Suez for goods shipped from southern ports like Shenzhen and Hong Kong is negligible.

Outside observers should take these initiatives seriously. The CCP clearly believes in the long-term gains that can be reaped from financing polar infrastructure projects that are otherwise economically unviable, particularly when strategic justifications exist, such as securing access to natural resources, or cargo routes that ease the Malacca dilemma. PRC financial institutions provided $12 billion of the $27 billion necessary to bring Russia’s massive new Yamal LNG project online. Prior to the PRC’s involvement, the project was floundering (Eurasia Daily Monitor, September 28, 2009). Likewise, in Alaska, Chinese financing rescued a 1,300 kilometer LNG pipeline connecting the North Bank with the Pacific. Western oil majors pulled out of the project because the gas would have been too expensive to extract at prevailing market rates, even though it was one of Alaska Governor Bill Walker’s signature initiatives (E&E News, April 17).

What to Watch For

Among the things to follow closely, observers wanting to gauge the progress of the Sino-Russian joint effort should keep an eye on three indicators:

- PRC investment in shipping infrastructure on Russia’s northern coast;

- PRC investment in Northern European transport infrastructure;

- Sino-Russian joint development of extra-wide next-generation icebreakers.

PRC media reports indicate that the first two are in the exploratory phase [1]. The last is speculative, but not entirely implausible. Much like the rest of its Arctic agenda, it is unclear whether Russia can afford the $2 billion-per ship price tag of its recently announced Lider-Class icebreakers—which could open paths wide enough for Panamax cargo ships—without PRC financial assistance (Maritime Executive, January 3).

Matt Schrader is the editor of China Brief. Follow him on Twitter @tombschrader. The author would like to thank Jamestown Foundation research intern Danny Anderson for his assistance in the preparation of this article.

Notes

[1] A prominent PRC think tank recently published a report outlining the need to build a “chain” of support and safety stations along the Russian coast to ensure the success of the Polar Silk Road (Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, April 18). Likewise, PRC media reports indicate PRC companies have held discussions with port and infrastructure authorities in Norway and Finland about infrastructure cooperation (International Financial News, October 10, 2017)