Domestic Criticism May Signal Shrunken Belt and Road Ambitions

Publication: China Brief Volume: 18 Issue: 14

By:

In the past two weeks, obvious signs of discontent with CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping’s ambitious policy agenda have emerged into public view. (Willy Lam explores these signs and their policy implications in “Xi’s Grip on Authority Loosens Amid Trade War Policy Paralysis”, also in this issue.) Intellectuals have launched brave attacks on Xi on a number of fronts, from his unprecedented assault on intellectual freedom, to his decision to name himself president for life by amending the PRC constitution to remove presidential term limits (China Brief, March 5).

One of these criticisms is Xi’s excessive ‘foreign aid’ to countries in Africa and elsewhere. This is an obvious reference to Xi Jinping’s ambitious, globe-spanning Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI is the hallmark of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy—indeed, as the scope of the BRI has expanded, the two have become increasingly difficult to distinguish.

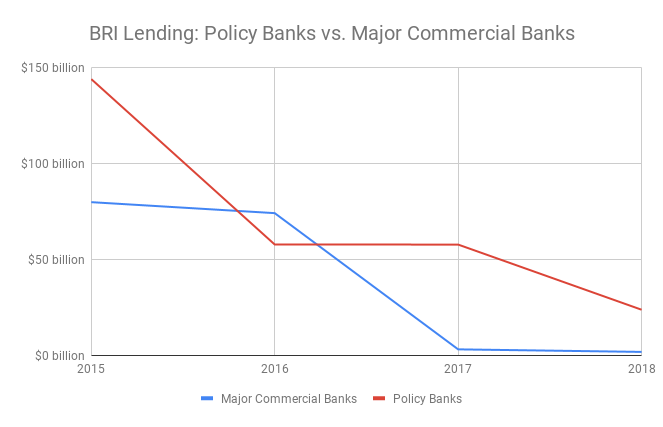

Although a Western observer might dismiss a few professors’ unhappiness with the BRI as ivory tower grumbling, PRC academic critiques are worth noting, since outspoken academics are often the channel through which other PRC societal elites communicate their dissatisfaction with the CCP. In the past, these channels have also served to telegraph important shifts in CCP policy. The public airing of such criticisms could indicate the existence of a emerging consensus that Beijing should scale back its BRI ambitions. And in fact, BRI lending has already begun to shrink, decreasingly dramatically since 2015. Were it to decrease further, it would have important strategic repercussions throughout the Eurasian landmass and Africa.

“Flashy” Spending Abroad

On July 20, Sun Wenguang, a retired professor of physics at Shandong University, penned an open letter criticizing China for “offering almost CNY 400 billion in aid to 166 countries, and sending 600,000 aid workers” (Canyuwang, July 20). On August 1, as he expanded on his concerns in an interview with the US-based Voice of America, police forced their way into Sun’s apartment. As he was taken away, Sun could be heard saying, “Listen to what I say, is it wrong? Regular people are poor, let’s not throw our money away in Africa … throwing money around like this doesn’t do any good for our country or our society.” (VOA Youtube, August 2)

Although Sun has long been a government gadfly, he is also long retired, and resides far from the center of power in Beijing. But similar criticisms have found voice much closer to the corridors of power. On July 24, Xu Zhangrun (许章润), a professor at Beijing’s elite Tsinghua University, published an extraordinary essay entitled “Imminent Fears, Imminent Hopes” (我们当下的恐惧与期待). Among many other criticisms, Xu excoriates Xi’s government for its profligacy abroad, saying:

At the recent China-Arab States Cooperation Forum [on 10 July 2018], [Xi Jinping] announced that twenty billion US dollars would be made available for ‘Dedicated Reconstruction Projects’ in the Arab world, adding that [China] will investigate offering a further one billion yuan to support social stability efforts in the [Persian Gulf]. Everyone knows full well that the Gulf States are literally oozing with wealth. Why is China, a country with over one hundred million people who are still living below the poverty line, playing at being the flashy big-spender? (China Heritage, August 1)

Observers steeped in Western coverage of Belt and Road might find these criticisms surprising. Western press outlets have tended to cover the BRI as a triumphant PRC bid to remake global trade in its image. Only very recently has Western coverage turned skeptical. But the political sensitivity of the BRI means that information related to it is tightly controlled inside China; as a result, Western analysis of BRI is largely irrelevant to the debate inside China. Domestic criticism of Belt and Road is drawn from a very different, distinctly Chinese context.

In the BRI, domestic critics see an extension of the CCP’s predilection for grand spending that disproportionately benefits connected insiders. As they see it, these loss-making “face projects” (面子工程) are conducted with limited transparency and oversight, and are primarily meant to reflect glory upon one’s superiors (and help underlings curry favor). The braver of Xi’s critics have thus taken to describing his foreign policy as dasabi (大撒币), or “throwing money around” (China Digital Times). The phrase, which censors have largely erased from China’s internet, is also a homonym for an extremely vulgar term used to insult someone’s intelligence.

Criticism vs. Reality

This jaundiced view of official spending may be why domestic critics of BRI sometimes categorize BRI investment—which is supposed to be primarily of a commercial nature—as “foreign aid” (对外援助). In reality, the “dedicated reconstruction projects” Xu Zhangrun referenced in his diatribe are not aid; they will be probably be financed by concessional loans meant to “drive economies by reviving industry” (以产业振兴带动经济; FinanceWorld, July 11). BRI loans are intended to be paid back, and despite numerous articles in Western publications about BRI-induced ‘debt traps’, analysts who track the initiative’s progress have found that only about 14% of BRI projects to date have run into problems (RWR Advisory, July 9).

This is not a point that domestic critics of BRI typically cite. Censorship may again be the culprit. Although an 86% success rate for BRI projects is certainly better than some Western observers might guess, the PRC government may not eager for it to be widely known at home that China’s banks have tens of billions of dollars tied up in problematic projects abroad. Indeed, the PRC’s policymaking apparatus appears to have already responded to concerns of BRI overreach by adjusting the scale of lending to limit possible financial risk. BRI lending by major PRC banks has dropped by 89% since 2015, and lending by commercial banks—who are dealing with their own financial issues domestically—has ceased almost entirely. Policy banks have also scaled back, despite their status as arms of PRC government policy.

Source: RWR Consulting [1]

Criticism has still emerged despite the government’s attempts to scale back risk. In this sense, the PRC government appears to be fighting the information and trust deficits engendered by its own censorship apparatus among intellectuals and other critics. Fed a steady diet of information trumpeting BRI moving from triumph to triumph, leery intellectuals remain skeptical.

A Less Ambitious BRI?

A sustained downturn in BRI lending at the same time that domestic criticism of the initiative emerges into China’s tightly controlled public discourse may indicate the existence of a emerging—and potentially enduring—consensus that Beijing should keep its overseas lending ambitions modest. In Beijing’s chilly intellectual climate, an academic brave enough to plainly state their criticisms typically speaks for many others. In pondering the future of the BRI, it might be instructive to recall a 2012 essay by Deng Yuwen (邓聿文), a commentary writer and deputy editor of the Central Party School’s journal, enumerating the ten biggest problems of the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao administration [2].

Although Deng was fired, many of his criticisms—including a lack of vision in PRC diplomacy, and the government’s failure to build an effective and convincing system of shared values—read like direct inspirations for Xi-era policymaking initiatives. Xu Zhangrun no doubt hopes his essay can serve as a similar catalyst, regardless of whatever fate may befall him individually.

Matt Schrader is the editor of the Jamestown China Brief. Feedback on this and other China Brief articles is welcome on Twitter at @tombschrader, or via email at cbeditor@jamestown.org.

[1] The author would like to thank RWR Consulting for use of their proprietary database of Belt and Road Initiative projects. 2018 figures are projected.

[2] The author is indebted to Jeremy Goldkorn, editor of the SupChina.com newsletter, for pointing out the congruencies between Deng’s and Xu’s essays.