Risky Business: A Case Study of PRC Investment in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan

Publication: China Brief Volume: 18 Issue: 14

By:

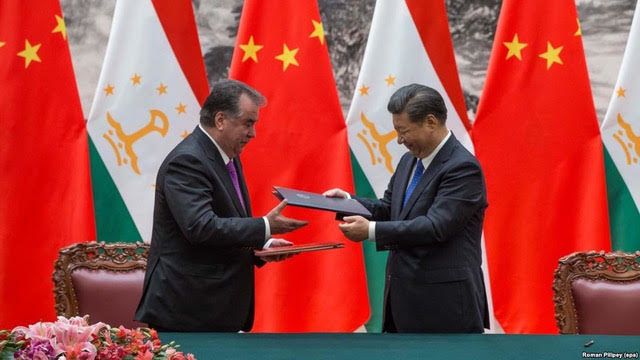

China’s “New Silk Road” or “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) has reached Central Asia in resounding fashion. As a result, the republics of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have seen large increases in Chinese presence and investment. Although both countries have overlapping needs, the degree and character of PRC involvement in each has differed. PRC investment in Tajikistan is characterized by expensive loans on infrastructure investment and energy projects that the country may be unable to repay (Avesta.tj, December 25, 2017). Kyrgyzstan, while having hosted similar projects, is also attempting to move the country into the twenty-first century by improving its transportation and digital infrastructure (Tazakoom.kg). Development experts classify both countries as “high-risk” for debt distress given public debt projections (Cgdev.org). However, despite the risk of such an outcome, both countries appear inclined to welcome PRC investment with open arms, as a way of funding needed investment like power generation and logistical links with the outside world.

Tajikistan

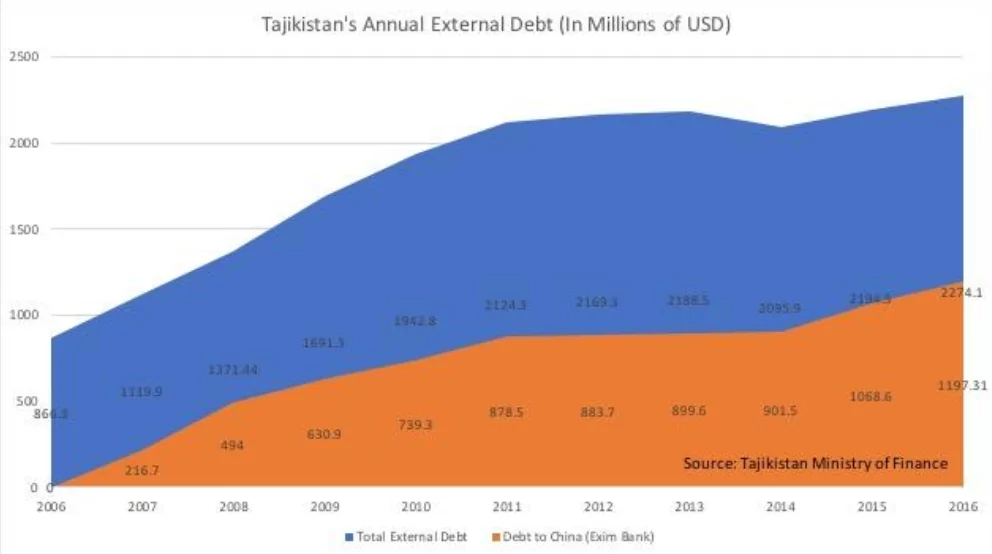

Tajikistan is one of the poorest countries in Asia, with an annual GDP per capita of $848, in a region where the current average is $6,200 (IMF). The country’s heavy borrowing reflects its diminished economic status. China is currently the country’s largest external creditor, with over $1 billion owed to China’s Export-Import Bank as of 2016 (Minfin.tj). According to the country’s Finance Minister, that amount increased slightly during 2016. The World Bank and the Asian Development Bank are Tajikistan’s two largest creditors behind China, with $318 million and $217 million in debt ownership, respectively, with the (most recent assessment) total external debt coming in at $2.9bn (Eurasia Daily, February 16).

While a large share of the approximately $1 billion in loans from China Export-Import bank to Tajikistan has gone to road projects, including a major highway between the two countries, most funding has gone to tackling Tajikistan’s energy crisis (The Diplomat, November 23, 2016). As recently as 2013, 70% of Tajiks experience extended power outages in the winter because of the country’s dependence on hydropower, the yields from which drop precipitously during the winter (World Bank, 2013).

Today the situation is not as dire; heavy PRC investment into the energy sector—primarily coal power plants—significantly improved Tajikistan’s power production picture. The 400 megawatt (MW) Dushanbe–2 plant, which was opened in 2012 and reached full generation capacity in 2016, helps keep the lights on in the capital. The plant’s construction was funded through $331 million in Chinese loans, paired with $17 million in funding from Tajikistan (bankwatch.org). TBEA, the Chinese company that built the plant, received the rights to and profits from multiple gold mines in the north of the country to offset the cost of Dushanbe–2 (News.tj, May 1).

Proposed and/or completed power projects discussed between the Tajik and Chinese governments (including Dushanbe–2) total 1,300 MW of potential power, from Dushanbe to the isolated Isfara District in the north (Avesta.tj, December 25, 2017). 1,300 MW can power approximately 850,000 to 1,000,000 homes, making China’s footprint in Tajikistan’s power sector impossible to ignore in a nation whose total population is 8.7 million. While the exact amount of PRC investment is not currently known, each of the new power plants will likely cost approximately $400 million (Avesta.tj, December 25, 2017).

Another noteworthy aspect of China’s likely future involvement in Tajikistan’s power sector: supplying coal. Right now Tajikistan imports its coal from other Central Asian countries, like neighboring Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. In 2016 alone Tajikistan imported 1.6 million tons of coal from those two countries, but their new projects will require around 500 million tons of coal (News.tj, February 20, 2017; Avesta.tj, December 25, 2017). While the country has three coal mines that can help pitch in, Tajikistan will likely have to purchase Chinese coal meet the new demand.

There are also geopolitical considerations to China’s investments. PRC investment is pushing into Russia’s near abroad, offsetting some of the financial load Russia used to shoulder. Russia’s financial role in Tajikistan has shrunk while its political involvement has grown. As recently as 2004, Russia wrote off $300 million in loans to Tajikistan for a military base south of Dushanbe (that has since been extended until the year 2042) and for a space surveillance complex (WPS.ru, October 22, 2004; TV Zvezda, April 26). According to the Russian Embassy in Tajikistan, the space surveillance system Okno (Window) is designed to be a part of an international framework to monitor the ecology of space and space junk, specifically (Dushanbe.mid.ru). However, in recent years the Russian-influenced Eurasian Stabilization fund, which is part of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), has provided only $161.4 million to Tajikistan, mostly for social and political reforms (eabr.org).

Kyrgyzstan

Tajikistan is not the only Central Asian country where China is leaving its mark; the PRC has also invested significant capital in BRI projects in neighboring Kyrgyzstan. BRI investment in Kyrgyzstan resembles that of Tajikistan in important ways. Lending from China has climbed sharply, to the point where $1.7 billion of Kyrgyzstan’s $3.8 billion in external debt is owed to China (24.kg, April 10). Like Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan’s debt to China is substantial; unlike Tajikistan, it is seeking to use PRC lending to invest in technological and transportation infrastructure.

Kyrgyzstan’s “Taza Koom” or “Smart Nation” program seeks to launch the Kyrgyz Republic into twenty-first century relevance with modern technological infrastructure, from faster internet connections to increased surveillance and security systems (Tazakoom.kg). As part of Kyrgyzstan’s ambitions to become a “digital hub” for China’s New Silk Road, PRC firms such as Huawei and China Telecom have partnered with the Taza Koom project (Kabar.kg, December 12, 2017). Huawei has stated its intention to help convert two of Kyrgyzstan’s largest cities into so-called “smart cities”: the capital of Bishkek and Osh to the south (Azernews, January 12). Smart cities allow municipal authorities to better monitor and manage their cities’ resources, and may improve traffic flow and emergency response times, among other benefits. However, they also bring with them the potential to enable more effective state surveillance, and to provide PRC intelligence services with electronic backdoors into target countries’ systems (China Brief, June 19). This may be, in part, an intended outcome; Kyrgyzstan and China have agreed to share intelligence and cooperate on security issues in some areas, including along Kyrgyzstan’s border with China’s restless Xinjiang region.

Where energy projects seemed to take precedence in Tajikistan, transportation projects have taken precedence in Kyrgyzstan, with a large sum of that going to the proposed railroad via Bishkek to Samarkand, Uzbekistan and beyond (Sputnik, March 20), as part of China’s planned New Silk Road rail corridor. Kyrgyzstan will likely cede access to some of its natural resources to China to offset some of the railway’s proposed $2 billion construction costs (Radio Azattyk, December 29, 2017).

Like in Tajikistan, geopolitics play a role in PRC investment in Kyrgyzstan, extending beyond infrastructure to integrated technical structures and intelligence sharing. During a state visit to China ahead of the SCO Summit in June, Kyrgyz President Sooronbay Jeenbekov and Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed to establish a comprehensive partnership that would promote further cooperation in trade and economic issues, and contained a pledge not to join any organizations to undermine the other (Xinhua, June 7). As part of the agreement, Kyrgyzstan also reaffirmed its acceptance of the PRC’s One-China policy.

As in Tajikistan, Russia’s involvement looks increasingly narrow when compared with that of the PRC. In Kyrgyzstan, it is largely focused on countering other regional powers. Kyrgyzstan only owes Russia $240 million, a payment plan for which was ratified in the Russian parliament earlier this year (TASS, February 1). The Russian military has a base in the country, and is exploring the possibility of to add another (See EDM, May 24). This is largely seen as a way to counter Chinese influence and have a more prime position to respond to and monitor threats coming from Afghanistan.

Weighted Down or Ready for Takeoff?

Even though Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are heavily in debt to China and will remain so for many years, both seem inclined to welcome the Belt and Road Initiative as a way to bolster their regional standing and fund needed infrastructure investment in a number of sectors. Many Tajiks will no longer have to deal with winters without power and heat, while Kyrgyz citizens will be more technologically integrated and have a stronger transit connection to the outside world via a new transcontinental railroad. With Russia constrained in its ability to match the PRC’s financial firepower, the close attention paid both these republics by China’s signature foreign policy initiative may help cement PRC influence in this corner of Eurasia for years to come.

Danny Anderson recently completed an internship at the Jamestown Foundation. He studied at American University’s School of International Service in Washington, DC.