‘Navruz Spirit’ Quietly Vanishes From Central Asian Leaders’ Agenda

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 16 Issue: 74

By:

The second Central Asian Leaders’ Consultative Working Meeting was supposed to take place this spring, in Tashkent. However, scheduling conflicts around the Navruz holiday (March 20, 2019) prevented the summit from convening. For a time, there were indications that the summit would simply be rescheduled for April 12 or some unspecified date later that month. But the leaders of the five participating Central Asian republics—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan—were ultimately never able to synchronize their schedules. For now, any information about when this summit will actually be held, if at all, remains elusive. The broad silence about why the quinquepartite presidential meeting has still not occurred this year indicates possible unexpected difficulties encountered by Uzbekistan’s government in hosting this regional summit (Kun.uz, April 10).

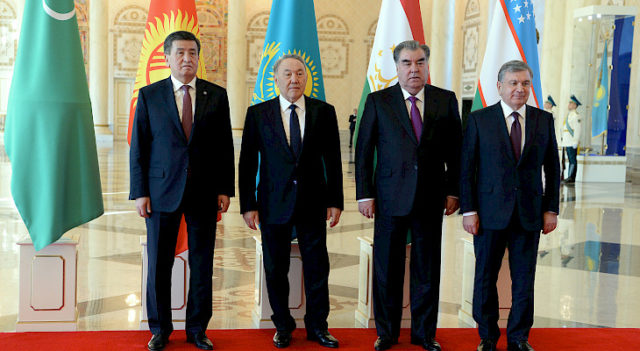

Last year, Kazakhstan’s then-president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, convened the first intra-regional Central Asian summit, after a ten-year pause. The spirit of the summiteers was upbeat, and the gathering resembled the long-awaited homecoming and reunion of brothers and close friends. Indeed, hugs, kisses and affectionate clasping of shoulders abounded (Akorda.kz, March 15, 2018).

The leaders explained at the time that the summit was taking place on the eve of the spring festival of Navruz, which symbolizes renewal of nature, spiritual purification and self-improvement of humanity. The first summit’s joint communique went on to say that “this blessed holiday epitomizes prosperity, unity, brotherhood and mutual support, [as well as] all those enduring cultural and historical values that unite Central Asian peoples” (Akorda.kz, March 15, 2018).

Overall, the March 2018 meeting imposed no obligations on anyone and created no unrealistic expectations, with the four participating presidents (President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow of Turkmenistan did not attend because of a previous commitment) only limiting themselves to general statements of intent. For example, the parties vaguely committed to achieving sustainable growth and the well-being of the peoples of Central Asia.

The summit also generated great interest in the international community. In fact, some Russian experts worried that the summit had been sponsored by the United States in an effort to limit the Kremlin’s influence and involvement in Central Asian affairs (Pravda.ru, March 15, 2018). One prominent Russian expert on Central Asian affairs, Arkady Dubnov, even expressed his belief that “holding this Central Asian summit, at a time when Russia’s relations with the West are deteriorating fast, indicates that Central Asian countries are trying to distance themselves from Russia” (CA-portal.ru, March 17, 2018). Yet, the reality, particularly one year later, looks significantly more restrained in terms of its short- to medium-term implications

The ongoing political transition in Kazakhstan will keep its leaders busy and preoccupied with domestic affairs, at least until the transition of power is complete following the presidential elections scheduled for June 9 (see EDM, March 27, May 16). In fact, the timing of Nazarbayev’s announcement, on March 19, that he was stepping down was perhaps was the main culprit for disrupting Tashkent’s plans to host the second Central Asian summit. After having been in power for almost 30 years, Nazarbayev curiously did not put off his resignation for another week or so.

Furthermore, March and April were quite busy months for the other Central Asian leaders. After hosting Russian President Vladimir Putin on March 28, Kyrgyzstani President Sooronbay Jeenbekov visited Germany from April 15 to 17 (Kabar.kg, March 29, April 16). Meanwhile, Tajikistan’s head of state, Emomali Rahmon, traveled to Moscow for a working visit on April 17 (News.tj, April 17). And South Korean President Moon Jae-in visited Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan on April 16–23 (Chosun.com, April 15). Finally, all Central Asian leaders except for Turkmenistan’s reclusive President Berdimuhamedow attended the One Belt One Road Forum in Beijing, on April 26 (The Diplomat, April 27).

These visits and international exchanges again demonstrated that Central Asian states’ relations with other non-regional players are apparently more important to their governments than relations with their closest neighbors. While meetings with Russian, Chinese and South Korean leaders have focused on investments, economic assistance and technology sharing, meetings among Central Asian countries have usually been stuck on difficult border and water-sharing disputes. Whereas, cross-border intra-regional trade still faces many hurdles and restrictions by Central Asia’s protectionist governments.

Failure to host the Central Asian summit constitutes a setback for Uzbekistani President Shavkat Mirziyoyev and his attempts to promote the “new spirit of goodwill, trust and willingness to solve common issues together with other regional countries.” Uzbekistani officials have attempted to take credit for the latest positive dynamics in relations among the Central Asian states. They describe these processes “as a completely new healthy climate, friendly atmosphere and favorable conditions for mutually beneficial cooperation not only between Uzbekistan and other respective Central Asian states but also among other Central Asian states themselves,” purportedly as the direct result of President Mirziyoyev’s outreach to neighboring countries (Financial Times, May 6).

However, these claims by Uzbekistani officials appear only partly true. Uzbekistan’s relations with all other Central Asian republics have, in fact, improved significantly in the last two years. But the same cannot be said unequivocally regarding relations between the other Central Asian countries. For instance, frequent border disputes between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan still have the potential for violence (Kaktus.media, March 13). Kazakhstan resorts to punishing Kyrgyzstan for the re-export of Chinese goods by occasionally shutting its borders to Kyrgyzstani trucks (Vb.kg, March 31). And Kazakhstani officials arrogantly remind Uzbekistan that its growing trade relations with Russia depend on the continuous goodwill of the Akorda (Kazakhstani presidential palace) (Ritmeurasia.org, February 19).

Even once trouble-free relations between Tajikistan and Turkmenistan soured late last year when Tajikistan-bound trucks and railway coaches coming from Iran were, for weeks, not allowed to cross Turkmenistani territory. This came after a senior Tajikistani railway official stated that the construction of the trans-Afghan railway line connecting Tajikistan with Turkmenistan and bypassing Uzbekistan was no longer needed after the improvement of Tajikistan’s relations with Uzbekistan (Rus.ozodi.org, Sep. 11, 2018; Catoday.org, February13, 2019).

When analyzing the disunity, disputes and divisions among the Central Asian states, some analysts tend to blame the meddling of certain outside powers. However, as the case of the abortive second Central Asian Leaders’ Consultative Working Meeting shows, such claims are perhaps exaggerated. The persistent troubles in relations among the Central Asian countries are largely of their own making and can be solved only through common efforts. But for that to happen, their strong-man leaders will presumably need to start meeting together in regional summits on a more regular basis.