Global Supply Chains, Economic Decoupling, and U.S.-China Relations, Part 2: The View from the People’s Republic of China

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 8

By:

Editor’s Note: Our April 1 issue contained the first part of this article series (Global Supply Chains, Economic Decoupling, and U.S.-China Relations, Part 1: The View from the United States), which focused on the issues and policy debates in America surrounding the prospects for U.S.-China economic “decoupling.” In this second part of a two-part series, analysts Ashley Feng and Sagatom Saha turn their attention to the complex policy issues surrounding economic decoupling from the Chinese perspective, and how this might affect the future course of U.S.-China relations.

Introduction: The World As Beijing Sees It

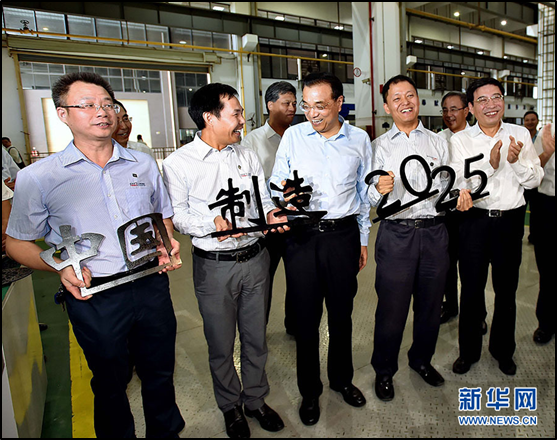

U.S. economic policy is not the only force at play threatening to disrupt the deep economic ties between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the United States (as discussed in part 1 of this article series). Chinese officials have also been driving a wedge. From the launch of the National and Medium- and Long-Term Program for Science and Technology Development (PRC State Council, 2005) to Made in China 2025 (PRC State Council, 2017), China has consistently pushed for self-sufficiency in specific sectors, limiting foreign exposure where possible . As the Trump Administration has adopted a more confrontational trade posture with China, introducing trade and investment restrictions, Beijing’s plans have only been accelerated.

However, the additional forces driving apart the world’s two largest economies are secular economic trends. The PRC faces a shrinking, shifting workforce that threatens to undercut its global manufacturing status, and a looming middle-income trap that encourages Beijing to compete with Washington in high-value-add sectors. Looking forward, the economic shock from the COVID-19 pandemic will likely make the United States and the PRC further averse to interdependence, if the pandemic has a lasting impact into the future.

Higher Wages, Fewer Workers

The Chinese workforce, increasingly smaller and skilled, is moving away from the attributes that cemented China’s central position as a low-cost critical link in many global manufacturing supply chains. First, China’s population pyramid is increasingly unbalanced. China’s population is forecasted to peak in 2029 at 1.4 billion people, and its dependency rate (the proportion of non-working people) has steadily grown since 2011 (Nikkei Asian Review, January 5, 2019). By 2050, China’s working-age population will have decreased by 200 million people (Social Sciences Academic Press, January 3, 2019). What’s more, the Chinese workforce has been steadily shrinking for roughly a decade, further driving up labor costs (Caixin, January 29, 2019). Chinese standards of living have also increased—due both to China’s economic growth and a higher-educated population—thereby pushing the labor force to further demand higher wages.

Second, Chinese wages are growing at pace with the Chinese economy. Even amidst the trade war, some Chinese provinces and municipalities continued to increase minimum wage standards in a bid to boost consumer spending amid slowing economic growth (SCMP, August 21, 2019). The push, along with the cancellation of tax preferences for foreign firms, has compelled foreign manufacturers to seek low-cost labor in Southeast Asian and elsewhere (WSJ February 9). Some international firms with global supply chains are already planning to leave: 40 percent of American firms surveyed by the American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) China and AmCham Shanghai said that they planned to shift at least part of their production out of China (AmCham Shanghai, May 22, 2019).

The future seems to hold more of the same as other developing countries enjoy relatively lower-cost labor, as well as improvements in the infrastructure and human capital needed for massive manufacturing hubs. The Chinese government, in pushing for wage growth over manufacturing output, recognizes that Chinese labor supply—increasingly educated and urban—will not be able to competitively fill low-value-add factories much longer.

Escaping the “Middle-Income Trap”

These trends in wage growth run contrary to the economic model that has powered Chinese growth since it entered the World Trade Organization in 2001. The PRC fueled annual gross domestic product (GDP) increases by adopting foreign technology, accumulating more factories, and exporting more goods to the rest of the world. However, that paradigm may not continue to work. Sub-Saharan African and Southeast Asian nations are developing their own competitive edge in manufacturing before China has sufficiently broken into the advanced sectors that drive growth in the United States alongside domestic consumption. In other words, China faces an impending middle-income trap, in which it would neither dominate manufactured-goods exports nor compete in services or technologically innovative industries. Chinese leaders have acknowledged that future economic growth is far from guaranteed (China Daily, October 5, 2017). In fact, China’s seemingly miraculous growth is actually quite precedented and slower on a per-capita basis than historical periods of rapid growth in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan (WSJ, July 17, 2019).

Acknowledging its economic dilemma, Beijing has been actively tipping the scales toward moving up the value chain. For example, the emerging Chinese workforce is much more suited toward the service sector, where the United States still maintains a trade surplus with the rest of the world. Since the mid-2000s, China has placed an increased emphasis on decoupling with a different name: indigenous innovation. Indigenous innovation, which was first mentioned in the National and Medium- and Long-Term Program for Science and Technology Development, is a bit of a misnomer—it doesn’t just mean investing and promoting innovation domestically, it also means to “localize production and intellectual property” (USCC, July 28, 2016).

This includes investing in strategic sectors abroad, bringing and relocating the personnel and technological know-how back to China. Since 1990, China has invested a total of $148.3 billion in the United States, peaking in 2016 with $46.5 billion (Rhodium Group, 2019). In Europe, China has invested $174.4 billion between 2000 and 2019 (Rhodium Group, April). Many of these investments are in sectors that China defines as strategic: such as information and communications technology (ICT), consumer products and services, energy, and the automotive industries.

Where China cannot get these products through legitimate means, such as through investments and acquisitions, it turns to illicit means (U.S. Trade Representative, March 22, 2018). As a senior German intelligence official once indicated, when China can attain high-tech companies through legal means, this corresponds with a drop in cyberespionage activities (SCMP, April 12, 2018). In the United States, intelligence officials noted that after the trade war began, Chinese levels of cyberespionage also picked up (NYT, November 29, 2018).

As the economic competition has picked up in both speed and intensity, so too have Chinese efforts to decouple from the United States. After the United States placed Huawei and its 68 subsidiaries on the Entity List, China’s efforts to decouple technologically from the United States only increased. The CCP ordered government offices to remove all foreign computer equipment and software mirroring Washington’s efforts to limit the use of Chinese technology. Chinese companies also began designing out American parts from their products, such as Huawei smartphones (WSJ, December 1, 2019).

China’s chances of maintaining comity in the international trading system seem slim if it successfully advances up the global value chain—especially in services, where the United States still maintains a trade surplus with the rest of the world. Such a move would put the PRC in even more direct, higher stakes economic competition with the United States and other advanced economies who possess a laundry list of economic grievances with Beijing. The PRC leadership nonetheless intends to move China up the supply chain anyway, in fear of getting stuck in the middle-income trap—in which emerging economies lose their competitive edge in manufactured-good exports without entering high-value-add segments of the global economy.

Contemplating the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

While Beijing has long prioritized achieving independence in critical technologies, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated concerns elsewhere—not only in the United States, but around the world—by demonstrating the disastrous consequences of global supply chains that lack domestic self-sufficiency. In March, the PRC, which dominates medical equipment markets, largely withheld respirator and surgical mask exports as it dealt with the coronavirus within its own borders. At least 80 other countries have officially limited or banned personal protective equipment exports with few notifying the World Trade Organization as required for members (WTO, April 24). The pandemic also punished those that relied on the PRC for coronavirus test kits, and multiple European countries have complained of receiving faulty testing kits, protective masks, and other critical medical supplies (Caixin Global, April 2). Many countries, from Australia to the United States, have called on domestic industry to fill the import gap.

Other countries fear that Chinese state-owned firms will opportunistically take over domestic companies with capital injected by Beijing. For example, India tightened its investment restrictions so that any foreign investor from a country that shares a land border must receive government approval (Economic Times (India), April 19). The rule, which already applied to Bangladesh and Pakistan, was aimed squarely at Beijing. Europe also appears vulnerable to bargain hunting with Chinese firms and funds eyeing acquisition targets on the continent. European countries, which have so far lagged behind the United States when it comes to screening foreign investments for national security concerns, have taken COVID-19’s threat to business seriously: France, Germany, and Italy have all announced measures that would strengthen protections against foreign takeovers (WSJ, April 20). Margrethe Vestager, the European competition commissioner, has gone as far as proposing that EU governments buy stakes in domestic firms to prevent Beijing from doing the same (Financial Times, April 12). Brussels has so far played a minimal role in national investment screenings, letting each country determine its own system—with some having none in place at all (China Brief, January 18, 2019).

The pandemic has revealed the glaring drawbacks in global “just-in-time” supply chains. For countries that rely on Chinese production, pandemic related disruptions (and the competitive free-for-all to purchase limited supplies) have highlighted the importance of domestic slack and redundancies. Insofar as foreign investment is a factor, governments have viewed it as a vulnerability to be patched rather than a remedy for unprecedented economic pain. It remains unclear what lasting effect the pandemic will have on the global economy, but it has thus far exposed faults and deepened the process of “decoupling.”

Conclusion: A Chronicle Of A Decoupling Foretold

If Beijing and Washington seek to decouple, global trends are cooperating. Chinese wages are increasing and Chinese workers are becoming fewer, making it difficult for Chinese factories to keep up the same level of production while keeping costs low. In light of these difficulties, Beijing is angling to move up the global value chain, which would place China in direct economic competition with the United States. If Beijing succeeds, China’s days as the world’s factory would be a relic of the past. Chinese firms would compete for market share in the same advanced manufacturing and service sectors as American firms, similar to the decimation of non-Chinese firms in the clean energy sector.

These underlying macroeconomic trends in China—rising wages, a shrinking and educated workforce, and the looming middle-income trap—have incentivized foreign companies to shift production elsewhere. The desire of PRC leaders and Chinese companies to shift to a higher-value economy frightens American businesses and the U.S. government, and U.S. policymakers have begun to take steps to mitigate potential harm and further losses to the U.S. economy. These actions by both parties, amidst the backdrop of growing economic competition and COVID-19, will only accelerate decoupling between the world’s two major economies.

Ashley Feng is a research associate in the energy, economics, and security program at the Center for a New American Security. She can be found on Twitter @afeng79.

Sagatom Saha is an independent energy policy analyst based in Washington, D.C. His writing has appeared in Foreign Affairs, Defense One, Fortune, Scientific American, and other publications. He is on Twitter @sagatomsaha.