Hungary Looks After Its Kin in Ukraine’s Carpathian Province

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 17 Issue: 79

By:

Ukraine’s Carpathian province (Zakarpattia Oblast) is comparable in certain key respects with Bessarabia in the Odesa province (see EDM, May 28). Zakarpattia is another outlying territory where Kyiv’s influence is weak, local power brokers well-entrenched, the infrastructure desolate, and ethnic minorities—in this case the local Hungarians—left largely to their own devices by an under-resourced central government (see below).

As a further similitude, Zakarpattia is also wedged narrowly between several countries; but its strategic location is even more interesting and more promising, surrounded as it is by four European Union member countries (Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania), with the potential to be turned into a Central European logistical hub on Ukrainian territory.

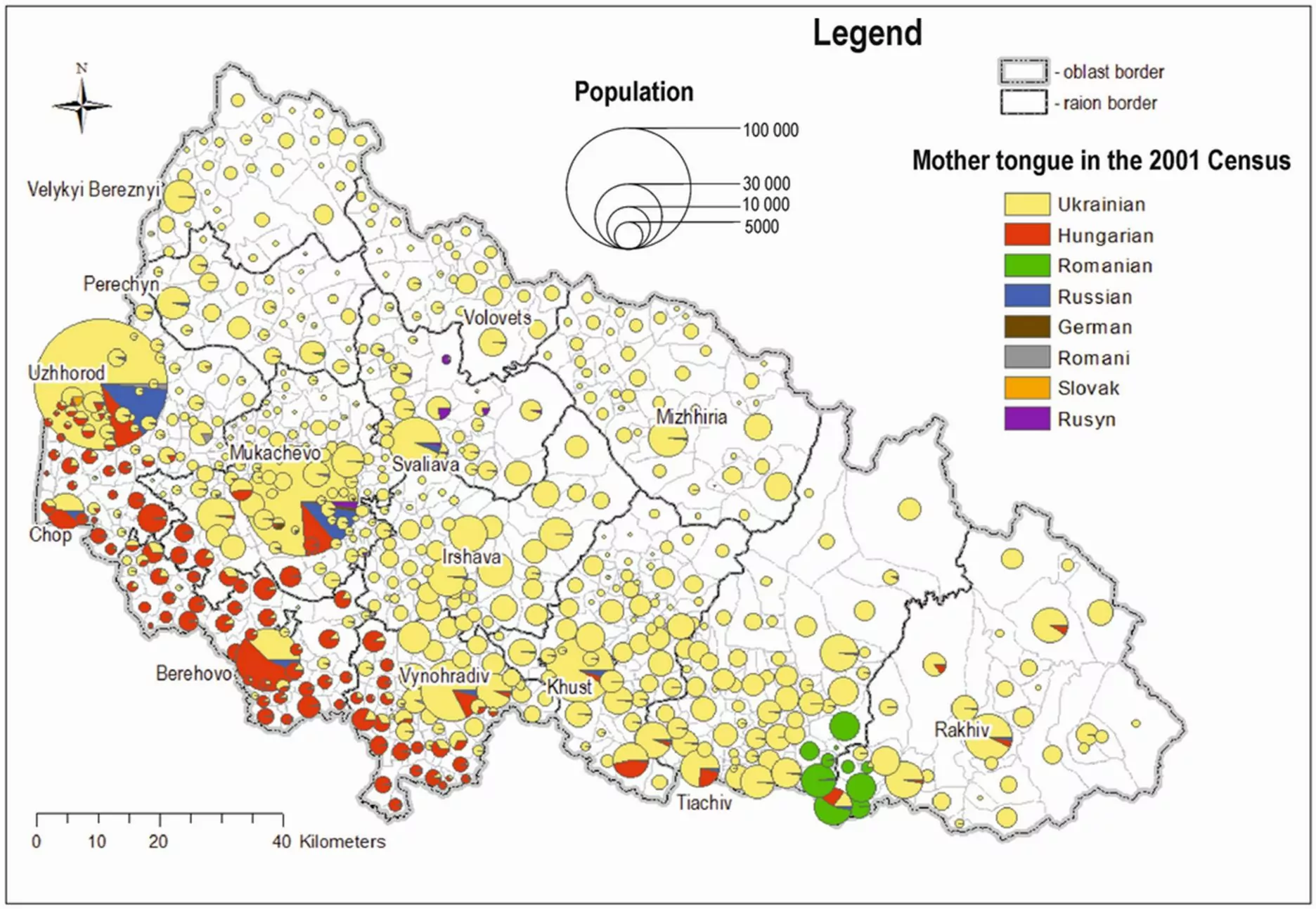

Ukraine’s natural gas transit system has its westbound outlet in the Carpathian province en route to the European Union. Pipelines with a combined capacity of 140 billion cubic meters per year (albeit at decreasing utilization rates) and three giant underground storage sites also in the Carpathian province comprise the largest concentration of flow capacities and storage capacities anywhere in Europe (Utg.ua, accessed June 1). These assets are mainly located in the Berehove, Uzhhorod, Vinohradiv, and Mukacheve districts (“raions”—see below).

This territory was Hungarian minority–ruled in one form or another during many centuries (this minority status is not new, but historically permanent). The present population numbers 1,260,000 for the entire Carpathian province, with 80.5 percent ethnic-Ukrainian and 12 percent ethnic-Hungarian residents. The share of Hungarian-speakers, slightly higher at 12.7 percent, indicates that Hungarians do not face Ukrainization pressures. The Hungarian minority of 152,000 is concentrated in the districts of Berehove (76 percent Hungarian local majority, 19 percent Ukrainian), Uzhhorod (58.5 percent Ukrainian, 33.5 Hungarian), Vinohradiv (71 percent Ukrainian, 31 percent Hungarian), and Mukacheve (84 percent Ukrainian, 13 percent Hungarian) (Ukrstat.gov.ua, accessed June 1).

Local Hungarians achieved substantial political representation in the 2015 elections to the provincial, district and town councils. The Carpathian Hungarian Cultural Association’s president, Laszlo Brenzovics, the foremost leader of this national community, was elected as a deputy to the Verkhovna Rada (national parliament) in Kyiv in 2014, on the electoral list of the Petro Poroshenko Bloc, based on a political agreement between them. In the 2019 parliamentary elections, however, the new President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s party, Servant of the People, won handily in Carpathian Ukraine, and no local Hungarian entered the Kyiv parliament. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban and other leading ruling Fidesz party officials campaigned aggressively for Brenzovics, to no avail. It is a fairly common practice for parliaments of European countries to allocate token seats ex-officio to representatives of small national minorities. The Ukrainian parliament has yet to introduce this practice.

Carpathian Hungarians, however, gained representation in the European Parliament via Hungary’s Fidesz party. Berehove resident Andrea Bocskor was elected in 2014 and re-elected in 2019, both times on the Fidesz list, in the European elections on Hungary’s territory. Bocskor has been particularly vocal on Hungarian and other national minority issues in European Parliament debates.

Hungary’s policy toward its kin in Ukraine is part and parcel of its systematic, occasionally intrusive, support to Hungarian minorities in all neighboring countries. A hallmark of Orban’s government, in power since 2010, this policy aims to preserve and strengthen the Hungarian minorities’ national identity as a core interest of the Hungarian state. As such, the support is well resourced and institutionalized through multi-year assistance programs on the ground. In Zakarpattia’s case, Hungary encounters a weaker presence of the Ukrainian state compared with that of Romania, Slovakia or Serbia in their respective Hungarian-minority areas.

The Ukrainian state, with its meager resources, does, nevertheless, support certain Hungarian cultural activities in the province: e.g., a drama theater and several pedagogical institutes that train teachers for Hungarian schools in the province.

Budapest, for its part, supports in Carpathian Ukraine a network of Hungarian-language libraries and cultural clubs, the Ferenc Rakoczy II Institute and College, activities of the Carpathian Hungarian Cultural Association and Carpathian Hungarian Teachers’ Society, local Hungarian-language TV broadcasting, and the Egan Ede business development fund (supporting thousands of local Hungarian-owned businesses), among other cultural and social programs. Senior Hungarian official Istvan Grezsa, reporting to Prime Minister Viktor Orban directly, coordinates since 2018 these programs on the ground. Separately from this, the grant of Hungarian citizenship (passportization) is highly attractive to Hungarian residents of Zakarpattia, one of Ukraine’s poorest regions. Those passportized hold de facto dual citizenship, which is illegal in Ukraine (Evropeiska Pravda, February 18, May 27).

Along with strengthening the minority’s national identity and cohesion, the Hungarian government views its kin in Carpathian Ukraine to some extent as a factor in Hungary’s economic and political life. With limited opportunities for local employment, many Hungarian-speaking residents of Carpathian Ukraine work in Hungary, helping to relieve the labor-force shortages there. Territorial proximity favors a circular labor migration that can contain long-distance, long-term migration of Carpathian Hungarians from their communities, helping to keep these together. Hungarian-passportized residents of Carpathian Ukraine tend to vote heavily for Orban’s Fidesz Party in Hungary’s elections (as do their kin from Hungarian minority communities in other neighboring countries).

Beyond the educational and social programs, Budapest is offering a €50 million ($56 million) credit line to the government in Kyiv for infrastructure development in Carpathian Ukraine. Possible projects include the construction of roads, modernization of the main Ukrainian-Hungarian border-crossing point (Zahony-Chop), the opening of additional crossing points, rehabilitation of the abandoned Mukacheve airport (to replace the existing Uzhhorod airport), and development aid targeted to Hungarian-inhabited districts. This credit line is a standing offer from Budapest since 2018. It is, however, implicitly linked to a mutually acceptable resolution of Hungarian minority grievances over language use and education in Ukraine’s Carpathian province.