Briefs

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 18 Issue: 21

By:

Islamic State Receives Loyalty Pledge from Myanmar’s Rohingya Militants

Jacob Zenn

Since 9/11, Islamic militants in virtually every country where they are waging an insurgency have allied or affiliated themselves with either al-Qaeda or Islamic State (IS). One of the rare exceptions, besides those fighting in southern Thailand, has been Rakhine State, Myanmar. Several hundred Rohingya Muslims from Rakhine have formed militant groups to combat increasing pressure from Myanmar’s military, which has pushed tens of thousands of Rohingyas out of the country and across the border into Bangladesh. Other Rohingyas have fled as far as Malaysia and Thailand by boat or, if they have the means and connections, to other countries in the Middle East, such as Saudi Arabia.

The Arakan [Rakhine] Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) formed in 2017 with the stated objective to enable humanitarian access into Rakhine and “fight for the liberation of persecuted Rohingya,” but it also explicitly asserted that it would not ally with al-Qaeda, IS, or Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba (Twitter/PichayadaCNA, September 14, 2017). Further, ARSA’s name lacked Islamic and certainly jihadist references, which suggested it had a somewhat secular orientation. Notwithstanding this, initial reports alleged that ARSA’s members received funding from the Rohingya diaspora in Saudi Arabia. The group’s leader, Ata Ullah, was raised in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and later preached at a mosque in Saudi Arabia, which implied some level of international links and, therefore, potential for Islamist influence (al-Jazeera, September 13, 2017). Ata Ullah had apparently returned to Rakhine secretly around 2016, helped launched ARSA’s first attack, and advocated that the group evolve from a humanitarian to a militant orientation, but still not necessarily a jihadist orientation (Dhaka Tribune, October 13, 2017).

Even if Ata Ullah did not desire for ARSA to become a jihadist group, India claimed al-Qaeda operatives of Bangladeshi descent with British citizenship were attempting to recruit Rohingyas to wage jihad against Myanmar and India (Times of India, September 19, 2017). Myanmar also sought to portray IS as attempting to infiltrate ARSA, while Indonesia and Malaysia lent support to Myanmar’s assertions about IS recruitment in Southeast Asia for the Rohingya cause (The Irriwaddy, April 29, 2019). Nonetheless, the remoteness of Rakhine and it bordering Myanmar and Bangladesh, with proximity to India—countries which are hostile to jihadists—would have made it difficult for IS to penetrate the province.

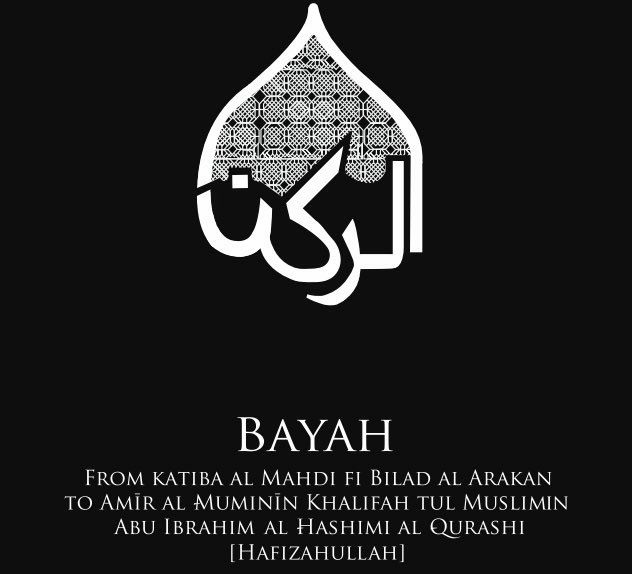

The lack of military success by ARSA and underlying Islamist currents among the group or other militant and humanitarian elements operating in or near Rakhine have led to the formation of a new jihadist group in Rakhine. This was evidenced by the November 5 pledge to IS “caliph,” Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Quraishi, by the new Katiba al-Mahdi Fi Bilad Arakan (Brigade of the Mahdi in the State of Arakan) that surfaced on jihadist social media platforms (Twitter/PatilSushmit, November 5). The pledge would seem unexpected—and perhaps even suspect—if not for IS spokesman Abu Hamza al-Quraishi’s October 18 audio (Terrorism Monitor, November 5). In addition to calling for jailbreaks and praising IS provinces, he also indicated that pledges had been made to and accepted by Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Quraishi, but he did not indicate from where the pledges came. It is certainly plausible, therefore, that one such pledge came from Rakhine.

The lack of major attacks by this new Rakhine jihadist group may result in delays from Islamic State in recognizing their pledge. Moreover, until further statements emerge from the Rohingya jihadists or IS, the pledge will not be confirmed. Nonetheless, this development suggests IS still desires to expand and the group may eventually claim attacks in Rakhine, just as it has done in neighboring Bangladesh (zeenewsindia.com, July 29).

***

Boko Haram Shekau Faction’s Signs of Life and Limitations in Nigeria

Jacob Zenn

On November 9, the Boko Haram faction led by Abubakar Shekau launched a daring raid in Gwoza, Borno State (Vanguard, November 6). The raid, involving four sport-utility vehicles with mounted weapons and a suicide bomber, was repelled by the Nigerian army, which also separately announced the arrest of a child soldier who was an “IED expert” (Facebook.com/DefenceInfoNG, November 15). If Boko Haram succeeded, it would have rekindled memories of 2014 in Nigeria, when Shekau made Gwoza the de facto capital of the “State of Islam” that he so declared from a mosque near the town (YouTube, August 25, 2014). Within one year, Shekau pledged loyalty to Islamic State, but he was dethroned from leadership of the new Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) in 2016. This led Shekau to revive Boko Haram, which had become inactive since 2015, as a separate group from ISWAP (Sahara Reporters, August 3, 2016).

Boko Haram’s operational tempo since 2016 has been significantly slower than that of ISWAP. The group’s largest attack since 2016 was also not carried out by fighters commanded by Shekau in Sambisa Forest, south of Gwoza, but by fighters under a Lake Chad-based commander, Bakura, whose branch affirmed its loyalty to Shekau—and not ISWAP—around September 2019 (Telegram, September 24, 2019). In March 2020, Bakura’s fighters carried out the attack on Chadian troops in Bohoma, Chad, which killed 92 Chadian soldiers and led to the short-lived Operation Bohoma Wrath overseen by Chadian President Idriss Déby (africaradio.com, April 10). Boko Haram activities have, since March, been reduced around Lake Chad. However, ISWAP, which was also targeted by Chad’s army during Operation Bohoma Wrath, still sporadically attacks Chadian soldiers. For instance, in October, ISWAP claimed its improved explosive device destroyed a Chadian vehicle and killed eight soldiers (africaradio.com, October 20).

Shekau’s most recent surprise attack in Gwoza could have been a boost for Boko Haram, but it wound up revealing his military limitations. He has nevertheless tried to compensate for his fighters’ weakened capabilities over the past year through periodic video releases. For example, after a French teacher was beheaded in France in October for showing Charlie Hebdo cartoons to his class, Shekau issued a video condemning French president Emmanuel Macron (Telegram, October 30). Shekau had also condemned France in a September video (Telegram, September 1). Given that Boko Haram distributes videos through its own social media channels, and not those operated by Islamic State or al-Qaeda, Shekau’s recent videos have barely resonated among jihadist audiences. Shekau’s outreach to jihadist recruits in Nigeria’s north-central Niger State and northwestern Zamfara State earlier this year—which involved the announcement of branches in both states in addition to preexisting branches in Lake Chad and Cameroon—is also yet to result in landmark operations in either of those two states (Telegram, July 7).

The presence of several hundred men praying in Boko Haram’s August video from Niger State nevertheless shows that Boko Haram maintains a following there (Telegram, August 5). Moreover, the continued presence of child soldiers in Boko Haram videos from Sambisa indicates that even if the group’s recruitment is not as effective as that of ISWAP, Shekau’s faction can sustain itself at least through raising children as jihadists (Telegram, November 2). ISWAP may be Nigeria’s paramount concern in Borno and the still active al-Qaeda-aligned Ansaru faction may be a greater threat than Boko Haram in northwestern Nigeria. Nevertheless, Shekau’s fighters remain a force to be reckoned with in Sambisa, Cameroon, and potentially again in Lake Chad and for the first time in Niger State and Zamfara. However, the group is now incapable of raiding military bases like it was during Shekau’s heyday in 2014. Reduced military effectiveness will still not deter Shekau from fighting until ‘martyrdom,’ as his latest November 17 video indicated (HumAngle, November 17).