Belarus as a Pivot of Poland’s Grand Strategy

By:

Executive Summary

For 500 years, Poland’s grand strategy successfully rested on building various points of leverage with the leaderships and societies in the East—in the so-called Intermarium, between the Baltic and Black seas—in order to prevent these areas from falling under Russian imperial domination and, thus, keep Russia out of Europe’s balance of power system. But this approach was interrupted by 45 years of “Atrophy” as a Communist puppet state of the Soviet Union and 30 years of post–Cold War “Geopolitical Pause” that was characterized by Poland’s “Strategic Restraint” in its foreign policy toward the East, including importantly toward Belarus. The geopolitical “sunny weather” is now over, however. And Poland is compelled to resurrect its older strategy toward Russia and Europe’s East. This situation also calls for critical adjustments (e.g., in military planning and force posture, active defense, stretching the enemy posture, adopting a proactive stance, more strategic signaling) in order to counter Russian New Generation Warfare toolbox with its versatile instruments of coercion in Russia’s western limitrophes.

Belarus is literally a pivot of the entire European Intermarium region because of the country’s geographic position astride the main east-west invasion corridors between Warsaw and Moscow. As such, Belarus’s status—either fully under Russian control or able to prevent the local stationing of Russian forces—has an outsized effect on the security of all nations and powers in the region. A change in Belarus’s status to an outpost for the Russian Armed Forces would trigger a cascading security dilemma for Poland and the entire Intermarium. This realization is already pushing Warsaw to abandon its heretofore Strategic Restraint in favor of a regional approach more aligned with Poland’s grand strategy of the last 500 years: an active policy posture toward Belarus coupled with militarily active forward defense capabilities.

Introduction

During the summer and autumn of 2020, Polish media was awash in reports coming out of neighboring Belarus, where not only is the fate of that country currently being decided but also the fate of the security status of the entire Intermarium region, including Poland. Amidst the turmoil that has engulfed Belarus for weeks since its falsified presidential elections, Russian activities in and long-term goals for that country may have serious implications for a territory of immediate security concern for Poland—the lands between Brest and the Smolensk Gate.

In September 2020, I took a car trip (as a passenger) from the Belarusian border on the Bug River to Warsaw. The journey lasted only the time it took me to complete two phone calls, browse Facebook, make one post on Twitter, and hold an hour-long discussion with subscribers to Strategy and Future on our Facebook group. And to my surprise, I was already on the bridge over the Vistula River in Warsaw even though my colleague and driver had not been speeding particularly fast. The 200-kilometer east–west voyage across flat and rather well-connected terrain felt shockingly quick compared to traveling by car from the Polish capital to Wrocław, Kraków, Gdańsk or the Mazurian lakes.

To put it bluntly: if Russian combat units, including in particular the 1st Guards Tank Army, were to be stationed in Belarus with all the necessary heavy logistics, this would drastically upend Poland’s current security status quo. Belarus transforms into a deadly threat to Poland if it comes under Russian military control and becomes a base of power projection for Moscow. Such a transformation would compel Poland to change its own force posture and contingency plans, while at the same time forcing the government to heavily recalibrate its military modernization plans.

This, for now, hypothetical scenario is somewhat reminiscent of the case of the partition of Czechoslovakia just before World War II. In the interwar period, until the fall of Czechoslovakia, the Germans could seriously attack Poland solely from West Pomerania. Only this area offered strategic depth and a sufficient operational basis that could support large German units and logistics lines to launch an invasion. East Prussia lacked all such necessary attributes, allowing for only an auxiliary strike. German Silesia, on the other hand, was flanked by Greater Poland (Wielkopolska region) and, above all, by Czechoslovakia, allied with France at the time. Thus, Germany could not plan to launch a strike on Poland from there, fearing a Czechoslovak intervention or the preventive action of the Polish Army on its rear or wing that could cut off its forces from the German core.

The collapse of Czechoslovakia dramatically changed this state of affairs, suddenly permitting the Germans to launch the main attack from Western Pomerania and Silesia simultaneously. And they did it, invading from Silesia to engage Poland’s Łódź Army and then the Modlin Reserve Army, which opened the way to Warsaw. In addition, the German military launched an auxiliary strike from East Prussia (from where it was the closest to Warsaw), crossing Polish defense lines near Mława.

Thanks to the partition of Poland’s southern neighbor, Germany also carried out an auxiliary but fateful strike from Slovakia, outflanking the pivotal Kraków Army, which was exceptionally crucial to the Polish war plan. Already on the second day of the war, the Kraków Army was in retreat, resulting in a cascading effect that broke the Polish armies’ ability to protect each other’s flanks and triggered defeats along the entire long front, thus compelling the commander-in-chief to order a pullback of all the Polish army formations behind the Vistula and San rivers.

Until the summer of 2020, Russia was not able to launch an attack on Poland from Kaliningrad Oblast without a prior long-term build-up of forces and logistics in Belarus. True, it could attack the Baltic States from the vicinity of Pskov and St. Petersburg, but not Poland. It could also have threatened to cut Polish communication lines to the Baltic States if Poland decided to help the Balts, but not mount a full and serious attack against Polish territory—unless, of course, Warsaw had sent most of its forces north across the Nemunas and Daugava rivers. The Kaliningrad exclave today is even less convenient as an operational base than East Prussia was for Germany; and at the same time, the Russians are quite concerned that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and Poland could seek to occupy the oblast itself. Hence, and contrary to popular belief, Russia does not actually base any important forces in Kaliningrad, which it considers “besieged.”

On the other hand, the presence of a full army-level Russian force in Belarus would mean that, similarly to Nazi Germany’s use of Silesia in 1939, the Russians could, from this convenient operational position, launch a major attack on Warsaw. This strike out of Belarus could come from at least two directions. The first might emerge via Grodno and Wołkowysk, north of the Narew River and in between the Narew and Bug river systems. And the second could originate from Brest and Damachava/Sławatycze, following several possible roads westward through Biała Podlaska, Radzyń, Siedlce, Międzyrzec, Mińsk Mazowiecki and then toward the Warsaw suburbs on the Praga (eastern) side of the Vistula River.

In addition, such forward-positioned Russian forces would be able to (as they have already done several times in history) move between Włodawa and Chełm in the direction of Lublin to Dęblin, toward the crossings on the Vistula River between Radomka and Pilica. This would allow Russia to circumvent Warsaw from the south, as the Red Army accomplished in 1944 and 1945. On top of that, if it were to launch an attack from Belarus via Ukraine—violating the latter’s sovereignty—Russia could create another operational line through Chełm, Lublin and Puławy, dispersing Polish defense efforts of Warsaw.

An auxiliary Russian strike could then emerge from Kaliningrad Oblast and proceed along the Vistula valley, further dispersing Poland’s defensive operations in the vast eastern part of the country, which is cut by the Vistula, Bug and Narew rivers. Such a successful maneuver by Russia would additionally eliminate any possibility of the North Atlantic Alliance to help the Baltics or Poland east of the Vistula. That would mean an end to NATO’s credibility and the United States’ security guarantees.

Belarus in Russian hands obviously eliminates the possibility of helping the Baltic States via the Suwałki Corridor in the event of a war with Russia, directly making the security status of these countries dependent on Moscow’s will. NATO planning will be affected heavily, while Alliance cohesion may be critically eroded given the increased risk of confrontation with Russia on unfavorable terms. The situation would be equally dangerous for Ukraine, for which the threat will appear from the northern border, close to Kyiv and within striking distance of the country’s main roads to the west, threatening communication with Poland and the West. Poland’s defense plans will have to be revisited. It is too early to say whether a real line of defense could be based only on the Vistula and the suburbs of Warsaw, but historical evidence would suggest that it might be possible. Regardless, the modernization of the Polish Armed Forces and war plans would all need to change. And in any case, the security of eastern Poland would come under doubt.

Moreover, the evident lack of capability of Western European states to project power in this part of the world, in particular in the event of the United States pivoting to the Pacific or retreating behind the Atlantic, could lead to a much sharper security dichotomy on the continent were Belarus to be absorbed by Russia. In that event, the security status of European countries within the Russian power projection umbrella would be dramatically different from that of the western continental powers of France, Germany or Spain. At the end of the day, everything boils down to the balance of power as well as each side’s willingness to use that power to enforce its political will and impose decisions that favor its own interests.

Background

The Baltic Sea “turns” near the mouths of the Vistula and the Nemunas rivers to the north, a spot that forms the northern edge of the isthmus that pinches the European landmass between the Baltic and Black seas—the so-called Baltic–Black Sea Bridge (a.k.a. the European Intermarium).[1] Considered by strategists of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as the most important of the geopolitical zones in Europe when it comes to shaping the balance of power, the Intermarium resembles a wide “transition strip” between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, connecting the continental masses of Eurasia with the western Europeean peninsula, which is open to the World Ocean and has for centuries been under the influence of the sea. Thanks to this great maritime connectivity highway, Western Europe hugely benefited from the Great Oceanic Revolution starting at the turn of the 16th century, with the geopolitical consequences resonant to this day.[2]

In contrast, the portion of Europe located closer toward Asia, starting from the eastern part of the Baltic–Black Sea Intermarium region, has a distinctly more continental character. The vast continental spaces have determined the directions of political and economic development of the region and, to a large extent, its status and political anchoring. The Black Sea divides this huge block of land hanging from the east, effectively separating it into two segments. And through there, relentless and incessant invasions from inner Eurasia repeatedly swept into Europe. The region’s dual nature—continental yet still “between the seas”—creates a peculiar spatial bloc, with three frontiers opening to Asia, though some require crossing the marginal seas around Europe.[3]

The transitional location of this place, between Europe proper and the vast stretches of Eurasia, has meant that both Western European political forces expanding east, as well as the political forces of imperial Russia spreading west have, unfalteringly, for several centuries, sought to subordinate or destroy all political organisms that sprang up in the Intermarium. Above all, they tried to prevent the creation of a unified political-state entity covering the region’s geographical whole. The Intermarium is a vast area, covering some one million square kilometers, and sovereignty over the entire territory would mean control over key strategic flows in Europe (that is, the movement of goods, people, troops, technology, capital, knowledge and data) across the main east-west axis of communication of the Northern European Plain and north-south between the two maritime zones of the Northern Atlantic and Black Sea, the latter of which naturally connects with the Greater Middle East, Eastern Mediterranean and the Caucasus. Every single modern-era war for domination over the European continent included a struggle for control of the Intermarium.[4]

Poland’s grand strategy for centuries viewed Russia as a landlocked continental power, whose core area was surrounded by five external powers: Sweden, Poland, Turkey, Persia and China—all located in the intermediate zone between the Eurasian Heartland and the Rimland.[5] Russia proper was separated from them by a buffer zone—the so-called “borderlands.” In Polish history these eastern approaches came to be known as the “Eastern Frontier.”[6] From this perspective, Russian history becomes a battle against these regional competitors for control over the borderlands. Occasionally, Russia (or the Soviet Union) became powerful enough to dominate the European continent. But when it sought to counter the consolidation of continental dominance by France or Germany, it repeatedly ended up allying itself in large-scale European or world wars with the world’s leading naval power at the time—the United Kingdom and/or the United States.

In that vein, the ultimate goal of Poland’s grand strategy has therefore always been (and is almost certain to remain) to keep Russia out of the European system of balance of power. And for the better part of the last 500 years, it largely succeeded, however that sounds to Westerners accustomed to inviting Russia to help balance the system for their own interests: be it to balance against Adolf Hitler, Kaiser Wilhelm or Napoleon or, currently, the French using Russia to balance against Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Today, Russia’s value to other powers pursuing balancing behavior (such as Germany, France or Turkey) is largely limited to its energy resources and military power projection capabilities. As such, neutralizing Moscow’s New Generation Warfare strategy, which involves combining military and non-military methods (including using energy domination as a political weapon), will nullify Russian ambitions to act as a balancer in the new game between Europe and China.

Even when Russia managed to achieve a forward position on the Central European Plain at various points in the past, this did not translate into a sense of security for the Russian government. East of the Elbląg–Kraków line, the physical space of the region forms a triangle, the base of which expands as one moves deeper into the Russian empire, thus inevitably forcing the Russian forces in this area to form thinner defensive lines. This allows a potential opponent of Russia the opportunity to choose the direction of a strike and to take advantage of its chosen directions. Polish forces have historically used this opportunity many times, and Russian strategic culture remains fueled by this fear.[7]

This great space from the Elbląg-Kraków line, before it reaches the current borders of Russia, is already thousands of kilometers wide, the terrain flat as a table; and once behind the so-called Smolensk Gate (a physical, 80-km-wide gap between the Daugava and upper Dnieper rivers, near the city of Smolensk, in present-day Russia), the layout of the area practically “invites” a further march eastward to seize Moscow. At the same time, however, for the offensive from the west, there is the issue of ever-longer communication lines throughout the entire area, from the Vistula valley to the foreground of Smolensk and beyond, to Moscow. The armies of Napoleon and Hitler collapsed in this area. The Poles assaulted Moscow along that route in 1605 and 1610, the Swedes after 1708. The French invaded this way in 1812. The Germans pushed into this area in 1914–1917, the Poles in 1919–1920 and Germans again in 1941–1942.[8]

Since the beginning of the Romanov dynasty in the 17th century, the Russians have repeatedly fought on the Northern European Plain and crossed the Smolensk Gate every 33 years, on average. Russian strategists and military planners presumably have a well-mastered sense of the military geography and patterns of movement and maneuver in this war theatre. In contrast, the United States has never operated east of the Oder River; nor has it ever been engaged in Europe in non-linear, limited warfare (often under the threshold of kinetic war) against a major power that thrives off this type of conflict.

In the Northern European Plain, Russia has three options. The first is to use strategic depth, resulting from space and climate, to pull enemy forces in and, by exploiting the vastness of the western buffer zone of the Russian empire, destroy the fatigued and overstretched foe (Napoleon, Hitler and the Swedes all suffered such a defeat). But this strategy runs the risk that once on Russian soil, the enemy might still be able to defeat Russian forces. And a further downside is the expected total destruction of the western provinces of the empire in war—as most recently occurred during World War II (with evidence of that conflict still visible to this day).

The second option for Russia is to face the enemy with large forces on the border and carry on a war of attrition. Tsarist Russia famously attempted this approach in 1914–1917, and it seemed like a sound strategy at the time given its more favorable demographics compared to Germany and Austria-Hungary. But it ultimately turned out to be a trap due primarily to the shaky social conditions within the Russian empire, where the weakening of the apparatus of coercion and control allowed the regime to fatally collapse in 1917.

The third option is to push Russian borders as far west as possible, thus creating more buffer areas—as Moscow did during the Cold War. This strategy seemed attractive to the Soviets for a long time because of the great strategic depth it provided along with the opportunity to increase the economic resources of the empire by exploiting the conquered buffer areas. But at the same time, it scattered imperial resources over the entire Baltic–Black Sea Intermarium and further up to the Elbe and the Danube, increasing the cost of military presence far from the core area of the center. This ultimately broke the Soviet Union and ended in the agreement in Belovezha (Białowieża) Forest, in western Belarus, decreeing the collapse of the empire in 1991.

Following Russia’s brief period of utter decline after 1991, the tumultuous Boris Yeltsin era gave way to the Vladimir Putin regime, which has sought, over the last two decades, to regain the country’s imperial posture and imperial footprint. Putin’s Russia embarked on New Generation Warfare to seize control of key locations in the western buffer zone that Russians call the limitrophes. Moscow employed the full toolbox of limited and non-linear warfare tactics so well known in Europe since the Middle Ages, effectively capturing (in one form or another) Crimea, Donbas, Belarus, the Caucasus and Transnistria.[9] Belarus is a key pivot in this game.[10]

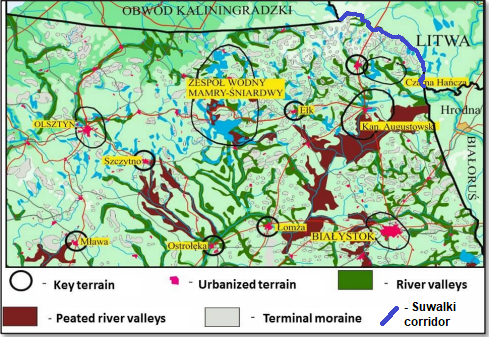

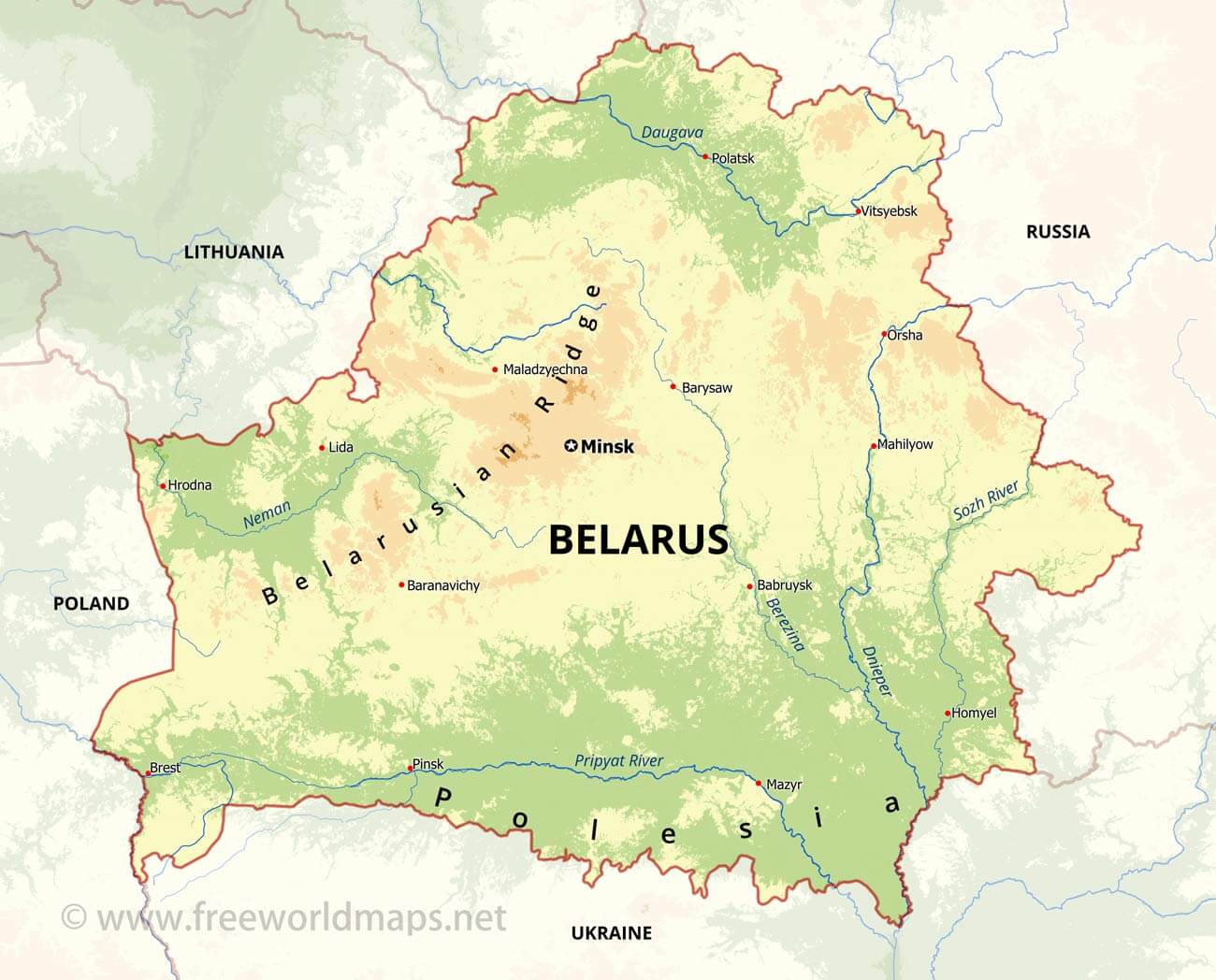

From Poland’s perspective, Belarus is potentially the most dangerous piece of real estate in its immediate neighborhood. Belarusian lands accommodate the northern direction of a Russian advance against Poland, stretching from Polesie[11] to the Daugava River, and bounded by the Nemunas in the west. It is an open, gently rolling terrain that provides relatively good observation conditions for military operations and is a perfect setting for tank warfare. Apart from the upper Nemunas and Szczara as well as the swampy valleys of these rivers, this region does not contain any major terrain obstacles. Herein lies the shortest and most convenient route for a Russian invasion of Poland, originating in Smolensk, Orsha and Vitebsk. An incursion by Russian forces in this area, following the relatively numerous and good-quality roads in the region, would separate Poland from the Baltic States and their seaports as well as restore Russia’s land connection with Kaliningrad, facilitating the supply of the Russian military in the westernmost oblast.

By projecting power across the Belarusian front from the Smolensk Gate, Russia can force the entire Polish front into retreat and shift the war—as has happened many times in history—to the central Vistula valley, and therefore to the heart of the Poland, thus paralyzing the main organs of its political will and compromising Poland’s defensive posture.

The corridor from the Polish core area toward the Smolensk Gate weaves through a tight arrangement of lakes, rivers, forests and lowland areas in northeastern Poland. Throughout its military history, Polish forces moving eastward would enter the Belarusian theatre of war via lands between Białystok and Wołkowysk (today, Vawkavysk in Belarus) and then proceed toward the Smolensk Gate. The old Polish warfare trail would cross the Nemunas River, in the narrowest passage between the riparian wetlands of the Biebrza and the Narew and the Białowieża (Belovezha) Forest. The trail then continues from Baranowicze (Baranavichy) to Minsk (with the northern passage from Lida) through Wilejka (Vileyka) to Połock (Polotsk); or it can cut straight from Vilnius to Polotsk, along the upper hinge of the Smolensk Gate.[12]

The gap between the upper Dnieper and the Daugava, which form the Smolensk Gate, is about 80 km wide and is predominantly a lowland plain covered with only scarce forests and cut through by two minor rivers. One third of its width is partitioned by mudflats (known in Polish as the Błota Weretejskie), 25 km long and 15 km wide.

The military significance of this corridor leading to Moscow is magnified by the fact that three major cities lie along the route: Minsk, Vitebsk and Smolensk. Additionally, Gomel lies slightly off this route. The Smolensk Gate traditionally shielded the heartland of Russia from the western powers and protected the capital of the tsars, Moscow, which lies only 480 km away.

One can compare the significance of the Smolensk Gate for Poland and Russia to the importance of the Golan Heights for Israel and Syria. The Golan is characteristically raised above the neighboring areas of Israel—Lake Galilee, Tiberias, the Jordan Valley and even the Valley of Gilboa—which make up the core of the country’s Galilee region. Israeli control of the Golan Heights, therefore, ensures that those low-lying areas remain relatively safe from threats emanating from Syria. At the same time, with the Golan Heights in the hands of the Israeli Armed Forces, the Syrian capital of Damascus (located less than 50 km from the eastern edge of these highlands) falls within reach of Israeli military units operating from high ground. The Golan forms a convenient operational base from which Israeli forces could potentially launch a rapid land offensive against Damascus, via the Quneitra Governorate—a strategic nightmare for Syria.

In turn, Syria’s possession of the Golan Heights—as was the case prior to the 1967 Six-Day War—prevented the Israeli core areas from being able to develop properly. Until Israel seized the Golan, settlements and kibbutzim in adjacent Galilee were continually disturbed by Syrian military activities. Moreover, in the event of a war and land invasion, the immediate danger of seizure threatened the entire Israeli area from the border with Lebanon, through Galilee, to the border with Jordan and the Gilboa valley, from where it is not so far to Tel Aviv or the Mediterranean coast.[13] This, in fact, occurred temporarily in the opening of the 1973 Yom Kippur War (which the Arabs call the Ramadan War), when superior numbers of Syrian armored forces flowed through southern Golan, threatening the brisk seizure of the Degania and Tiberias areas, on the shores of Lake Galilee.

When it comes to the Smolensk Gate, the areas proximate to the Daugava and Dnieper rivers are convenient for large force maneuvering. Of the small rivers and streams crossing the Gate, the only significant ones (each of them is about 20 meters wide) are the Luchosa and the Kaspla. The western end of the Smolensk Gate, extending out around 90–120 km, is covered by a group of Lepiel Lakes, channeling traffic toward the Berezyna River, near Borisov. The muddy Berezyna valley in wet seasons “closes” access to the Gate. The area around Lepiel is an important crossroads from which two natural routes lead to Moscow: one south, passing the Dnieper on the right, to Vyazma, through the Smolensk Gate; and the other north, through Vitebsk and along the banks of the Daugava to Rzhev.

From the Belarusian city of Orsha, the Dnieper River flows through a wide valley that features abundant spring floods and numerous lakes and oxbow lakes; the roads through this area traditionally encouraged the building of dikes. In contrast to the Vistula, which is not always suitable for fording, it was possible to ford the Dnieper across the dry run up to the mouth of Berezyna. The Berezyna, all the way to the mouth of Hayna River, flows within muddy banks overgrown with bushes, making it difficult to cross; only a small number of places permit forces to descend and ford. One convenient crossing point is located near the city of Borisov—known thanks to the legendary retreat of Napoleon’s Grand Armée in the autumn and winter of 1812. Forests stretching along the river, becoming wider to the south, add to the difficulty of passage across the Berezina, thus increasing its importance as a natural defensive line. The Lower Pripyat, meanwhile, has no useful areas for fording at all. By contrast, the Daugava River has quite a lot.

In his memoirs of the 1920 Polish-Soviet War, General Władysław Sikorski interestingly recounts that, as a result of the success in the war of 1919–1921, some Poles “dreamed” of reconstituting Poland’s eastern borders from before the Andruszów Truce of the 17th century. This would have extended interwar Poland’s eastern territory beyond the strategic defensive line of the Daugava and Dnieper rivers, reaching as far as Velikiye Luki, Vyazma, Bryansk or Poltava (all inside modern-day Russia). Such a deep extension into Russia proper would have geo-strategically consolidated Poland’s forward defensive areas, while additionally screening the great rivers’ line that had historically served as a traditional boundary between the Polish and Russian worlds and former empires. For other strategists at that time, however, the minimum plan should be to secure the old borders of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from before the First Partition,[14] to be more or less based on the strategic line of the Dnieper and Daguvas rivers. In the end, however, less was achieved in the Riga Peace Treaty. The Polish military won the war that decided the fate of all Intermarium nations; but Poland failed to secure a lasting peace anchored on effective defensive lines. It took only 20 years for regional great powers to unwind Poland’s precarious security architecture and, ultimately, to destroy its independence in September 1939.

Even a century later, the above discussions are not trivial descriptions of some irrelevant geographic outcomes of past wars. Indeed, current developments roiling Belarus are pushing Poland to think hard about its active defense measures and to consider how to deal with novel concepts related to the ongoing Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA)—i.e., long-range fires, fire maneuver, or force multipliers rooted in long-range and advanced sensor technology. All these issues force a rethink of the competition for advantage in situational awareness that characterizes modern warfare. And if such a modern war involve Russia, it would primarily be waged throughout the Intermarium, across a key axis of advance from the Smolensk Gate, toward Poland.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the strategic goal of post-Communist Poland became to support the emergence of independent countries between itself and the Russian Federation as well as to cultivate positive neighborly relations to prevent these newly sovereign states from falling back into Moscow’s orbit. At the same time, after 1991, the western portion of the Intermarium undertook ever-tighter geopolitical integration with the Atlantic, characterized by deepening cooperation with Western European countries and joining the two key Euro-Atlantic structures, NATO and the EU. In recent years, this trend has been conspicuously represented by the United States’ growing forward military presence in Central and Eastern Europe.

Juliusz Mieroszewski and Jerzy Giedroyć, reputed Polish émigrés who lived in exile in the West following the end of the Second World War, formulated a geopolitical doctrine for Poland that contained a simple maxim: “There can be no free Poland without a free Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine.”[15] According to the two émigré activists, the very fact of the existence of these independent eastern neighbors would remove the danger of another Polish clash with imperial Russia because the two countries would be physically divided by a belt of independent countries formed from former Soviet republics. Indeed, Poland’s grand strategy in the East pursued by the governments in Warsaw after 1989 followed this “Mieroszewski-Giedroyc doctrine” fairly closely—underpinned as it was by the understanding that the eastern buffer areas determine the history of Poland, condemning it either to the position of a satellite or to independence. As Mieroszewski pointedly wrote in the political-cultural monthly Kultura, in 1974,

A precondition for Poland’s satellite status is the incorporation of the ULB [Ukraine, Lithuania and Belarus] to Russia. It would be crazy to regard the problems of Ukraine, Lithuania and Belarus as an internal Russian matter, in order for Poland to ameliorate its relations with Russia. Competition in these areas between Poland and Russia has always been aimed at establishing an advantage, not at good neighborly relations. For Russia, the incorporation of the ULB countries is a necessary precondition to reduce Poland to satellite status. From Moscow’s perspective, Poland must be a satellite in one form or another. History teaches the Russians that an independent Poland has always […] tried to establish its advantage in the ULB area. This equates to the liquidation of imperialist Russia’s position in Europe. This equates to the fact that Poland cannot be independent if Russia is to maintain its imperial status in Europe. From Warsaw’s perspective it is the same—only the other way around. We were looking for an advantage in ULB, whether military or federal, because history teaches that Russia in these areas is an insurmountable opponent. And you can only expect captivity. Even without World War II, Poland’s independence would be threatened because we won in 1920 near Warsaw, not Kyiv. Even without [Joseph] Stalin, there would be an arms race and the reduction of Poland to the role of a protectorate by Russia alone or together with Germany.[16]

It is worth coming back to the 1990s for a moment. At the peak of the possibility of fulfilling Poland’s aspirations to join the West along with the rest of the Baltic–Black Sea Intermarium countries—i.e., just 25 years ago, at the moment of Russia’s deepest collapse and amidst the most profound sense of Smuta (depression) under the rule of Boris Yeltsin—the population of this part of Europe was, in fact, greater than the population of the Russian Federation. Moreover, the combined GDP of the Intermarium countries was 16.5 percent higher than Russia’s GDP when the latter hit rock bottom, right before the bounce back that began under Putin’s rule.

Later on, once Poland became anchored inside NATO and the EU, Polish foreign policy came to embody what could be termed “strategic restraint”—a deviation from the previous 500 years of Polish grand strategy. Specifically, the overarching goal of joining the world of free strategic flows, which would underpin economic growth and democratization, encouraged Poland to adopt Western solutions wholesale; but this began to restrain the country’s attained leverage in the East for the sake of cohesion within the collective West. In seeking to square this circle, Warsaw attempted to “use” the material and institutional power of the West to promote the expansion of Western influence in countries east of Poland. Unlike in the previous 500 years, the Third Polish Republic did not rely on its own strength to build up “assets” and sources of “leverage” east of the Bug river; rather it sought to harness the strength of Western organizations and institutions. This strategy had mixed and sometimes disappointing results: Poland and the Baltic States joined NATO and the EU on the one hand, but Georgia, Ukraine and Belarus achieved limited to no European integration on the other hand.

This belief in the unshakeable preponderance of the West in the international system after 1991, combined with the dedication to preserve the cohesion of the collective West, ultimately somewhat undermined Warsaw’s historical efforts to establish Belarus as a buffer crucial to the existence and proper functioning of an independent Poland. And current developments in Belarus acutely illustrate that the last 30 years of sunny weather are over and the principles of realpolitik in international relations have returned to the fore. Unless the small (or middle) powers in the region react collectively, the balance of power will change, too. Yet while the countries of the Baltic–Black Sea Intermarium have reacted differently than France and Germany to the crisis in Belarus, they do not wield sufficient leverage to enforce their own policies. The only leverage is the impulse of the rebellious Belarusian society, which is not enough since street demonstrations, even if they were overtly pro-Western, cannot single-handedly change Belarus’s orientation vis-à-vis Russia. By failing to build interdependence with Belarus over the last 30 years, Poland today lacks any meaningful points of leverage that might helping both the Belarusian regime and society develop more practical, economic and pecuniary bonds with it and the wider West.

In such matters, the balance of power is decisive and would have to change for the status of Belarus to change. For Russia, the status of Belarus is critical. In the West, it is believed that Moscow is ready to engage in open war to maintain Belarus’s status as a Russian ally, while the West itself is by and large not; moreover, Europe lacks the capabilities for such an operation. Finally, Western Europeans generally consider the countries in Poland’s region too weak to constitute the object of international politics as they are not net exporters of security and thus cannot influence the status of Belarus—particularly, if that change in status contradicts the national interests of a great power ready to go to war over this issue.

These observations presumably should affect Polish thinking about:

- Poland’s security in Europe, including within the context of the consolidation of the European project;

- Poland’s policy toward the East; and

- Poland’s position and perceptions of Poland elsewhere (including Western Europe) as well as the strength and status of the entire region.

Over the last 30 years, the region has suffered from a progressing breakdown of the post–Cold War consensus as Germany and France have sought to revert to “concert of powers”–style relations with Russia vis-à-vis affairs in the Baltic–Black Sea Intermarium. Those arrangements have routinely undermined intraregional aspirations toward greater unity as well as a consolidation of the Intermarium and its separation from Russian domination. Those policies threaten to split Europe—an issue of vital concern for Poland.

And Belarus is not the only casualty of such policies by the main Western European powers. Indeed, Poland’s own relative security is perceived rather differently from Warsaw compared to from Paris. France, largely toothless as it is in the Intermarium, wants to avoid any confrontation over Belarus with Russia, military or otherwise. This raises serious doubts as to Western Europe’s security guarantees to the Intermarium region as well as its dedication to consolidating the European project if the US were to eventually withdraw from the Old Continent.

And that perceived reality serves as a serious wake-up call for Warsaw, encouraging it to learn to rely primarily on its own Armed Forces. All these reservations and doubts notwithstanding, from a hard security standpoint, the alliance with the United States is more meaningful for Poland than its military links with Western Europe. The US Armed Forces are significantly larger and generally much more capable, despite the fact that they are mostly based far from Poland and do not have their center of gravity in the region. Crucially, so long as the US commitment to its Intermarium allies remains steadfast and tangible, the Russian side cannot be confident of its ability to control the escalation ladder in the event of a crisis—a stark contrast to Moscow’s more dismissive views of the militaries of continental Europe.

In this situation, and to rationally hedge against a hypothetical future refocus of US priorities away from the region, Poland has no choice but to try to find other ways it can shake Russian certainty as to the latter’s control of the escalation ladder in the Intermarium. After Poland regained its independence following the end of World War I, the country’s leader, Marshall Józef Piłsudski, argued that there is room for maneuver for Polish politics in the East, for example in the implementation of the Międzymorze (Intermarium) concept,[17] and in other activities aimed at building instruments of regional pressure and political influence. Indeed, the instruments of Western policy do not reach the eastern buffer zone or are ineffective there; therefore, Western powers must take Poland into account when it comes to the balance of power in this region. When it came to Polish policy toward the West, Piłsudski assessed that without its own agenda, Poland would have to be obedient in all directions and secondary to the will of the then–Western powers. Deprived of agency in this way, Poland would be forced to accept the will of powers from outside the region, thus limiting Polish maneuvering in the fields of security as well as development, business and capital penetration.[18] Piłsudski’s recommendations, in short: in the west of the continent, Poland was nothing, while in the east, Poland was a key player, and this role should be protected and cared for.

In that vein, French President Emanuele Macron’s efforts to discuss the region with Russia, without France having any significant instruments of leverage there, were met with deep skepticism in Warsaw. Paris (as other Western European capitals) has become accustomed to Poland adhering to its “strategic restraint” posture of the last 30 years. But that era is coming to an end. The result of this “strategic restraint” was a Polish reluctance to take any actions in the East that could have developed historically familiar instruments of political leverage over the elites of the new (former Soviet) buffer states.

In absence of credible assurances that the regional balance of power will inevitably remain in the West’s favor, the political-security situation in Central and Eastern Europe grows more complex—as illustrated by the following example:

The Belarusian city of Grodno, located just on the other side of the Polish border, is a major transportation hub on the Neman (Nemunas in Lithuania) River. This is the place where Lukashenka deployed paratroopers following the disputed August 9, 2020, elections in order to signal that he is still in control. And it is where he invited Russian troops to exercise that September, amid tensions on the Belarusian streets following the rigged vote. If Poland and NATO were needed to help consolidate Baltic defenses, Grodno would hang over the Polish right flank’s movement to Vilnius and Kaunas: along Road No. 16 as well as along highway S8, between Suwałki and Marijampolė (Lithuania). It is “felt” all the way from Białystok to Augustów and in Augustów itself and its bypass. Due to the convenient area for attack through Sokółka and Kuźnica, which would be open to Russian forces coming out of Grodno, Białystok could be cut off from both the south and the east, blocking Polish movements from the right flank and threatening them non-stop. Moreover, the right flank of Polish movement cannot be leaned against the Neman, which should be a natural decision given the terrain and the logic of the battlefield. The area itself, along with the need to perform the task of coming to the aid of the Balts through the Suwałki Corridor, effectively “invites” a preemptive neutralization of Grodno by Western forces capturing the bridges on the Neman in order to eliminate the Grodno communication junction, which threatens the Polish projection of force to Vilnius and Kaunas. This operation, of course, would entail a political and military escalation with Belarus and Russia, which stands behind Minsk. It is not coincidental that Grodno used to lie along the Warsaw–Vilnius communication line and, to this day, forms a key node of a critical Intermarium transportation corridor.

That said, taking Grodno will require reaching further inside Belarus to seize the junction in Volkovysk and in the town of Mosty, on the Neman. Such an operation would, in turn, create the temptation to secure the entire line of the Neman River, cutting Belarus in half in order to lean on this river and the bridges on it. This, of course, would surely draw Belarus fully into the war with all escalatory consequences including Russia.

Therefore, it is worth closely studying the 1920 Battle of the Neman River, which followed the Battle of Warsaw and sealed Poland’s military victory in the Polish-Soviet war of 1919–1921. The main targets of the Polish operation at that time were Grodno, then Lida, in a deep left flanking movement, and finally the entire line of the Neman River, utilizing an encircling movement through Druskininkai, north of Grodno.[19] One can assess the key ways in which this area does not align with the political boundaries left by Stalin and the collapse of the Soviet Union. This reality of difficult-to-defend present-day political boundaries translates into a substantially more difficult task for Polish armed forces on NATO’s eastern flank. And this becomes a strategic challenge for Poland should Alliance security guarantees prove shaky or if a power vacuum develops and creates a lethal security dilemma in the region.

Even without land incursions of western Belarus, Grodno would have to be reconnoitred by drones, special forces and surveillance monitoring (the Polish situational awareness system); and Polish forces would have to ensure airspace dominance (including regarding enemy helicopters) as well as the ability to react to the enemy’s fire maneuvers. Nevertheless, Grodno would ideally have to be eliminated as a threat to ensure proper Allied movement through the Suwałki Corridor and deep into Lithuania. This in itself would engage considerable Polish forces. Before any forces could depend on the Suwałki Corridor, much work would need to be expended to secure these maneuvers, including ensuring a firing advantage (under the effective situational awareness system) on at least the flanks to protect against flanking or breaking the flank in conditions of low military saturation and war maneuvering.

In modern conditions, combat on the battlefield is dominated by the maneuverable, mobile actions of troops in an extended field of interaction with poorly shielded areas or completely uncovered flanks. Flank control is achieved through situational awareness control, maneuver flexibility and fire maneuver. This is the situation to expect for Polish and allied NATO forces’ movement around the Suwałki Corridor facing Grodno. And the exact same issue would affect units facing Russian forces moving against Poland through Belarus. The main methods for defeating Russian troops would involve preemptive fire and situational awareness control during the various phases of a pre-kinetic and kinetic confrontation as well as in a reconnaissance battle for situational awareness superiority. All this makes the case for active defense that reaches far into Belarus, toward the Smolensk Gate.

On the opponent’s side, one has to reckon with deep forays behind Poland’s front lines, bypassing Polish/Allied force groups, cutting Poland’s and NATO’s stretched communication lines, causing logistical chaos, as well as creating an active combat front in the Polish rear with subsequent coordinated strikes from all directions. Increasingly, the center of gravity of war is shifting away from the mass of the enemy and its combat systems and toward command and communications. Deprived of communications and command, for example deep inside Belarus, Russian troops would have no real combat value in a scattered battlefield. In fact, such “blind and deaf” units could now be effectively “encircled,” depriving them of combat strength with a fire maneuver and disabling their situational awareness system. Such an approach represents a whole new way of fighting, in which technology and multipliers replace mass and numbers. Poland does not face a giant anymore, and understanding this must help guide a restoration of its historical grand strategy.

Conclusions

After 45 years of existing as a Communist puppet state, followed by 30 years of geopolitically sunny weather, Poland is now waking up to the need to devise a new grand strategy rooted in 500 years of history of combating Russia. This redevised grand strategy is built on an understanding of the continuing importance of the strategic borders of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, stemming from the ruthless logic of the Smolensk Gate. Undeniably, a rapid incursion of enemy forces via the Smolensk Gate toward the Vistula valley would threaten Poland’s very existence, while undermining NATO cohesion and setting off a cascade of effects that test the Alliance unlike any event in its history.

Poland must additionally bolster its toolkit to counter Russia’s New Generation Warfare instruments. Deprived of them, Russia will no longer be in a position to so strongly or destructively influence events in Europe. In contrast, efforts by some Western European capitals, notably Paris, to invite Moscow into various balance-of-power schemes at the expense of the Intermarium region will stress Polish relations with those European powers. France’s attempts to bring Russia to its side in the Eastern Mediterranean is already a harbinger of such dangerous realignments.

Meanwhile, the collapse of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty will itself affect Polish military planning, particularly when it comes to active defense concepts such as developing long-range fire and missiles. Acquiring long-range strike capabilities creates considerable opportunities to influence the opponent in the entire rear area and throughout the operational theater, including the combat impact on second and third echelon units, logistics bases, airports, equipment warehouses, electronic warfare systems, installations supporting operational activities, river crossings, logistics centers and the supply system, etc. Belarus is the place from which Russians would threaten Poland. Therefore, this makes Belarus a pivot of Poland’s grand strategy.

With an adequate saturation of firepower and the efficient and uninterrupted operation of tracking and guidance systems, it is possible to extend the battlefield deep into the enemy’s territory and, thus, significantly complicate the rival’s planning and combat operations as well as potentially deprive the opponent of the operational initiative in aviation—assuming the enemy’s air bases are within range. The acquisition of such capabilities as part of Poland’s own active anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) defense would need to plug into a modern and (this is worth emphasizing) proprietary situational awareness system in the Belarusian operational direction, as far as the Dnieper and Daugava lines encompassing the Smolensk Gate. That, combined with the impact on all communication nodes, bridges, bases and enemy concentrations, will be the foundation of a novel active defense concept for Poland.

Obtaining such abilities would significantly improve Poland’s chances of preventing a Russian strike by hitting the depths of the theater of operations, where a quick maneuver by enemy forces would threaten the capital city of Warsaw itself. This would also complicate the Russians’ planning of quick deployment and marching operations through Belarus. In cooperation with Ukraine, it is possible for Poland, through active defense in the foreground, to strengthen the chance of success in a war with Russia in the event of a blockade of bypass crossings through the Pripyat, which would change the geometry of the front. While this would require a firmer Polish-Ukrainian alliance, the benefit of making it happen could change the Russian strategic situation: Russia would now find itself flanked from broad southern and southeastern directions. If the security architecture in Europe crumbles, such a Polish-Ukrainian alliance might be the only other viable option for Warsaw.

Demonstrated measures of active defense will need to be robust and credible enough to create a security umbrella in the Intermarium capable of protecting at least against Russia’s low-intensity coercion methods. In that case, Russia may find itself also unable to start major offensive land operations without first having to neutralize the North Atlantic Alliance’s regional surface-to-surface strike systems and observation systems that deliver force multipliers. This would undermine the Russian dominance of the escalation ladder and could give Poland time for additional preparation, allied assistance and diplomatic maneuver in the event of a brewing conflict. Moreover, other domains of New Generation Warfare designed to give the Russian military the upper hand in a conflict may themselves be at risk: energy blackmail, market access, strategic flows control, disinformation, propaganda, cyber operations, sanctions, etc.

Accordingly, Poland and its regional allies’ resilience against Russian New Generation Warfare will grow if augmented by the hard-power measures of a credible active defense. The Intermarium can be protected, at least by denial, through indigenous deterrence by punishment; but this also requires thinking about how to address the entirely different challenge posed by Russia’s nuclear capabilities. Protection by denial should suffice because the Russian civilizational project is not attractive to its western neighbors. It is enough for Poland and its Allies to demonstrate their ability to eliminate Russia’s perceived military advantage in the Intermarium for the whole edifice of Russian regional dominance to collapse.

Notes

[1] Eugeniusz Romer, Polska. Ziemia i Państwo [Poland: Land and the State], Kraków 1917.

[2] Ryszard Wraga., Geopolityka, strategia i granice [Geopolitics, Strategy and Borders], Rome 1945.

[3] Andrzej Piskozub, Dziedzictwo polskiej przestrzeni [The Inheritance of the Polish Space], Ossolineum 1987; Ryszard Wraga, Sowiety grożą Europie [The Soviets Threaten Europe], Warsaw, 1935.

[4] Jacek Bartosiak, Rzeczpospolita między Lądem a Morzem. O wojnie i pokoju, Warszawa 2018; Feliks Koneczny, Dzieje Rosji, Warszawa 1921.

[5] The concepts of the Heartland and Rimland were, generally speaking, proposed by Halford Mackinder and Nickolas Spykman, who divided Eurasia into the landlocked Heartland and a coastal Rimland. The Heartland did not profit from ocean-faring, trade and connectivity and, as a result, was not prone to control by sea powers. While weaker economically, it nonetheless mastered great armies capable of controlling and operating in the vast continental steppes. In turn, the Rimland was the vast and rich coastal area of the Eurasia, affluent and vibrant and interconnected via sea but prone to domination by sea powers. The Rimland is where, since 1945, the United States has established a network of offshore military bases and system of alliances—arguably conforming in practice the above theory. Russia and China, meanwhile, have no doubt they accurately embody the Heartland.

[6] Jacek Bartosiak, Rzeczpospolita między Lądem i Morze. O wojnie i pokoju [The Republic Between Land and Sea: On War and Peace], Warsaw, 2018.

[7] Władysław Sikorski, Nad Wisłą i Wkrą, Studium z wojny polsko-rosyjskiej 1920 roku [On the Vistula and Wkra: Studies of the 1920 Polish-Russian War], Warsaw, 2015.

[8] Józef Piłsudski, Rok 1920 [Year 1920], Warsaw, 2014; Józef Piłsudski, Pisma zbiorowe [Collective Written Works], Warsaw, 1937.

[9] Vadim Cymbursky, Ostrov Rossiya [Island Russia], Polis, issue 5, 1993.

[10] Marek Budzisz, The Unknown Father of Russian Contemporary Grand Strategy, Strategy&Future, Warsaw, 2020 https://strategyandfuture.org/en/the-unknown-father-of-russian-contemporary-grand-strategy-part-1/ ; https://strategyandfuture.org/en/the-unknown-father-of-russian-contemporary-grand-strategy-part-2/.

[11] A forested area that sits astride the Belarusian-Ukrainian border.

[12] Roman Umiastowski, Geografia wojenna Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej i ziem ościennych [War-Time Geography of the Republic of Poland and Neighboring Territories], Warsaw, 1924.

[13] Jacek Bartosiak, Smoleńsk Gate and the Golan Heights, Strategy&Future, Warszawa 2019; https://strategyandfuture.org/en/smolensk-gate-and-the-golan-heights/.

[14] Sikorski, Nad Wisłą i Wkrą, 2015.

[15] Juliusz Mieroszewski, “Rosyjski kompleks Polski i obszar ULB” [“Poland’s Russia Complex and the Area of the ULB], Kultura, 1974, no. 9 (324).

[16] Mieroszewski, “Rosyjski kompleks,” 1974.

[17] Międzymorze (Intermarium) was an idea in the early 20th century to create a federation of the nations in Central and Eastern Europe that could jointly counter Russian (and German) imperial designs on the region. By its design, Poland would serve as an anchor of this project. Poland under Józef Piłsudski went to war in the spring of 1920 and seized Kyiv in order to consolidate a Ukrainian state that would form a key element of the Intermarium federal concept.

[18] Bogdan Urbankowski, Józef Piłsudski do Polaków. Myśli, mowy i rozkazy [Józef Piłsudski to Poles: Thoughts, Speeches and Orders], Warsaw 2017.

[19] Tadeusz Kutrzeba, Bitwa nad Niemnem, wrzesień–październik 1920 [Battle of the Neman River: September–October 1920], Warsaw 1926.