Hong Kong Cracks Down on National Security Imperatives Amid Electoral Reforms

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 8

By:

On April 15, Hong Kong celebrated National Security Education Day (NSE Day) for the first time in the special administrative region (HKSAR)’s history. The mainland has held a National Security Education Day on April 15 each year since the holiday was designated in a July 2015 National Security Law of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In Hong Kong, NSE Day was marked by a symposium of events held by the Committee for Safeguarding National Security, a body established by a new national security law implemented last June and led by the city’s chief executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor (China Daily, April 13). The theme of the day was to “Uphold National Security, Safeguard Our Home—Improve Electoral System, Ensure Patriots Administering Hong Kong.”

NSE Day was heralded by a concerted propaganda effort, as pro-Beijing forces appeared to signal their victory over the opposition. Upon reviewing the day’s events, foreign analysts could not help but question “what, exactly, is being celebrated on National Security Education Day, if not the police force and its use of force tactics (China Digital Times, April 15).[1] More than anything, it signaled the success of Beijing’s effective crackdown on the autonomy and independence of the HKSAR.

National Security Education Day 2021

The day was marked by speeches from Carrie Lam and Director of the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the HKSAR Luo Huining (骆惠宁); police force and correctional service open days; school activities throughout the city organized by the Education Bureau; and a “National Security Exhibition,” among other events (Info.gov.hk, April 13; nsed.gov.hk, accessed April 22). In her opening speech, Carrie Lam said that national security was inseparable from regime security, and that “to genuinely secure national security, the right to rule must be tightly gripped in the hands of patriots” (HKFP, April 15). This echoed PRC leader Xi Jinping’s words in response to a work report that Lam delivered in January that Hong Kong’s stability and security can only be ensured through “patriots governing Hong Kong” (爱国者治港, aiguozhe zhi gang) (Xinhua, January 27).[2]

At the police academy, officers staged “Chinese military-style drills and ‘goose-stepping,’” while prison officers showed off their capabilities to put down a mock riot by fending off “inmates” wielding canes and slippers (HKFP, April 15, April 15). For onlookers, these bore eerie callbacks to police brutality during the 2019 Hong Kong protests (see [1], China Digital Times, April 15). Schools organized national security-themed activities such as knowledge quizzes, poster design and slogan creation competitions under the direction of the Education Bureau (Info.gov.hk, April 15), which has played a major role in the dissemination of an all-encompassing concept of national security that covers sixteen priority areas, including “political security, homeland security, economic security, ecological security, cyber security, and cultural security…” (Nsed.gov.hk, accessed April 20; ST Daily, April 14).

Beijing’s top official in the HKSAR Luo Huining gave a speech calling the day’s events “a significant effort made by the SAR to fulfill its constitutional obligation of safeguarding national security” and noted that “security is the foremost prerequisite for development.” “Now that we have a law, a mechanism, and a team the implementation is ever more important,” Luo said, adding “For all who endanger national security, hard resistance should be stricken down by law, [while] soft resistance should be regulated by law” (Central People’s Government Liaison Office in the HKSAR, April 15).

Electoral Reforms

The Improving the Electoral System (Consolidated Amendments) Bill 2021 was introduced to the Legislative Council (LegCo) for the first and second readings a day earlier, after the basic reform outlines were first signaled at the PRC’s “Two Sessions” annual legislative meetings in early March (China Brief, March 15). City administrators and official news sources have all signaled that the electoral reforms are an integral part of ensuring the “political” element of national security in the HKSAR. Amendments to Annex I and Annex II of the Hong Kong Basic Law preparing the way for the reforms, also referred to as the “patriots governing Hong Kong” resolution, were approved by the NPC and passed into law on March 31 (Global Times, April 14). It is expected that the electoral reform bill will pass after its third reading in May, establishing new election regulations ahead of the upcoming Election Committee contest on September 19, LegCo polls (delayed last year ostensibly due to the coronavirus pandemic) on December 19, and the Chief Executive election to be held on March 27, 2022.

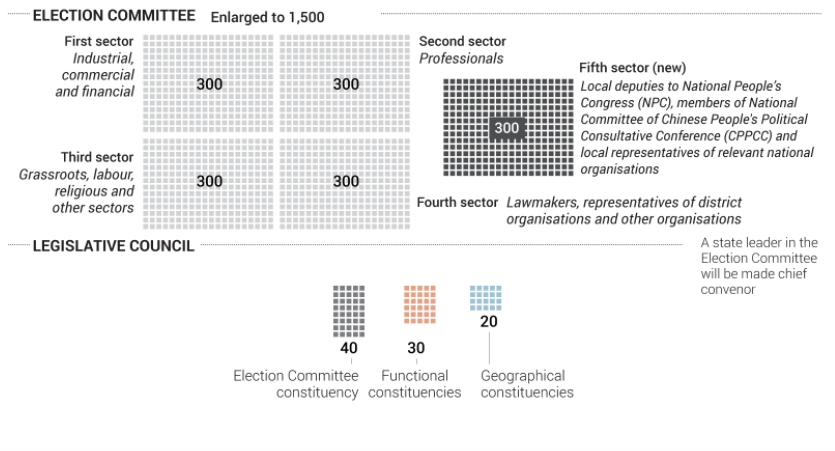

Overall, the changes are designed to undercut the ability of the popular opposition—already effectively stifled after pan-democratic lawmakers resigned in protest last November—to participate in government. They include cutting the number of directly elected seats from 35 to 20 in LegCo, which has also been restructured and expanded from 70 to 90 seats. The reforms will also set up a new vetting committee for aspiring political candidates, which is not subject to judicial review and will be overseen by the Hong Kong police national security unit and the Committee for Safeguarding National Security. The biggest change, however, revolves around empowering and expanding the Election Committee—originally tasked with picking the Chief Executive, it will now select 40 members of LegCo and effectively control all elections in the city. The remaining 30 LegCo seats will go to trade-based functional constituencies, long seen as being loyal to Beijing. The Election Committee itself will be expanded from 1,200 to 1,500 members, with the 300 new representatives coming from so-called “ultra-loyalist” groups that have strong ties to mainland organizations or government bodies (SCMP, April 14).

Lawmakers preempted an expected public outcry by planning to criminalizing acts of “openly inciting” people to cast a blank vote or spoil their ballot (Nikkei Asia, April 13), although legal experts warned that such legislation could have “real constitutional problems” and raise legitimacy problems for Hong Kong’s future elections (SCMP, April 15).

Crackdown on Education, Arts, Media

According to one mainland expert, the combination of last year’s national security law and this year’s electoral reforms have effectively controlled “secessionist voices” in the political area, but other aspects of Hong Kong’s economy and culture are infiltrated by subversive anti-China elements and still need to be dealt with (Global Times, April 14). To this end, the Education Bureau issued sweeping guidelines to improve national security education back in February, with new regulations covering everything from school management to new curricula and guiding student behavior off campus (SCMP, February 4, China Digital Times, February 4). A campaign to reform so-called “liberal studies”—designed to enhance students’ understanding of “national security, lawfulness and patriotism”—was rolled out in early April (Global Times, April 14).

The arts and media have also been targeted. After pro-Beijing politicians and media attacked the West Kowloon Cultural District’s M+ Museum’s plans to exhibit a work by the Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei, the cultural district authority chairman promised that M+ would not be “run like a grocery store” and that there would be no room for “vulgar” exhibits that violated the national security law (The Standard, March 30). Chinese regulators’ calls for the technology company Alibaba to divest its media assets, including the South China Morning Post, sparked concerns in March that a Chinese state-owned enterprise could soon acquire the 117 year-old paper and end long-running internal debates about its editorial independence (Quartz, March 19). Most recently, the pro-Beijing paper Ta Kung Pao issued a call to shut down the pro-democracy tabloid Apple Daily in order to “plug loopholes in national security,” just as the paper’s notorious founder Jimmy Lai Chi-ying was sentenced to fourteen months in prison for his participation in the 2019 protests (Ta Kung Pao, April 16; CCTV News, April 16).

Conclusion

As China has continued its crackdown on freedom of expression and political activities in Hong Kong, foreign criticism and sanctions have done little to blunt the central government’s determination to control the HKSAR at all costs. By applying a wide-ranging holistic definition of national security, the PRC under Xi Jinping’s leadership has moved rapidly to crack down on political debate, artistic expression, and educational and media freedoms in the HKSAR, while retroactively reframing its definition of “one country, two systems” to justify increasing control. There are also signs that the PRC will move to impose its censorship regime on the Internet in Hong Kong, which was previously exempted from mainland restrictions. Amid these rapid changes, the future of the island’s long-standing liberal autonomy looks grim.

Elizabeth Chen is the editor of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, feel free to reach out to her at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] Although there have been no official investigations into the numerous accounts of police brutality during the 2019 Hong Kong protests, multiple independent investigations as well as international human rights groups have found evidence of police misconduct and abuse (hkpfreport.org, accessed April 20; tl.hkrev.info, accessed April 20; HRW, November 19, 2020). As a result, the Hong Kong Police Force (HKPF), although technically a nonpartisan entity, has long been seen as a key Beijing ally and has consistently ranked low in public opinion polling (HKFP, May 20, 2020).

[2] Since Xi’s statement in January, central government propaganda organs have worked to establish the historical context of “patriots governing Hong Kong,” arguing that it is merely a reformulation of Deng Xiaoping’s declaration that “the people of Hong Kong [should] govern Hong Kong” (港人治港, gangren zhigang) (CGTN, March 4). A recent article in the Chinese Communist Party theoretical journal Qiushi lays this logic out clearly, while also arguing that the notion of “patriots ruling Hong Kong,” not autonomous and independent governance, is the core principle of the “one country two systems” framework governing mainland-Hong Kong relations (Qiushi, April 16).