UN Human Rights Clash Strains Credibility of Chinese Diplomacy

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 13

By:

On June 22, the Canadian Ambassador to the United Nations (UN) delivered a joint statement to the 47th session of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) on behalf of 44 countries expressing grave concern about the “repression of religious and ethnic minorities” by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). The statement urged “immediate, meaningful and unfettered access to Xinjiang for independent observers” and also noted continuing concern about the deterioration of freedoms in Hong Kong and Tibet (Government of Canada, June 22).[1]

A press release by Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian (赵立坚) noted that Belarus had delivered a joint statement on behalf of 65 countries that supported China and stressed “respect for the sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity of all countries” and “oppos[ed] interference in China’s internal affairs under the pretext of human rights” (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), June 22).

The exchange has brought China’s alleged human rights abuses into the spotlight again, as well as highlighting the hidden politicking behind such tiffs. Chinese diplomats reportedly pressured Ukraine into withdrawing its support after it became the 45th country to sign on to the Canada-led letter by threatening to withhold the delivery of Chinese-made COVID-19 vaccines, which one anonymous Western diplomat described as “bare-knuckles” diplomacy (AP, June 25). Other media reports said that Israel’s support for the Canada-led statement came after significant pressure from the U.S., marking a shift from Jerusalem’s previous unwillingness to criticize Beijing on human rights issues (Times of Israel, June 23).

Background

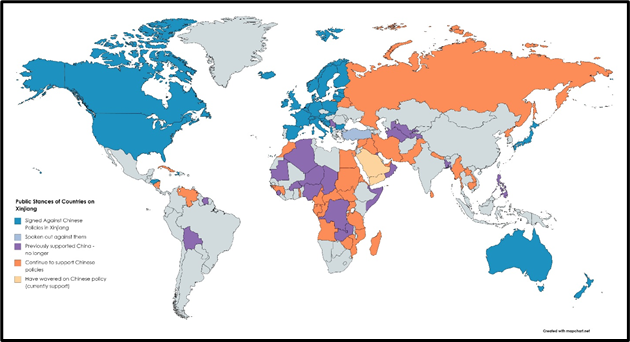

Such diplomatic fights over the Xinjiang issue have been perennial after the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) first received credible reports on the Chinese state’s systemic oppression, extralegal detention and mass surveillance of ethnic Uyghurs in Xinjiang in 2018 (CERD, September 19, 2018). China (through proxy countries such as Belarus and Cuba) and mostly western democratic countries have issued dueling statements at the 41st UNHRC session in July 2019, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) Third Committee in October 2019, the 44th UNHRC session in July 2020, and the October 2020 UNGA Third Committee (SupChina, October 7, 2020). They will likely repeat this at the 76th session of the UNGA Third Committee in October. Each time, both sides have been bolstered by growing numbers, although support has shifted slightly over time (see map below).

This March, a number of UN human rights experts raised “serious concerns” about the alleged detention and forced labor of Muslim Uyghurs and encouraged China to “respond positively” to several UN mandates’ long-standing requests to conduct official visits to China (OHCHR, March 29). In May, 152 countries took part in a virtual hearing that demanded China grant “immediate, meaningful and unfettered access” to Xinjiang. The UN special rapporteur on minority issues, Fernand de Varennes, notably said that the UN’s failure to more strongly criticize China in the past was “timid” (South China Morning Post, May 13, 2021).[3] A Chinese spokesperson hit back, calling the meeting “a political farce” and complaining that “while the U.S. and some other Western countries talk about ‘human rights in Xinjiang,’ they are actually thinking about using Xinjiang to contain China” (PRC Permanent Mission to the UN, May 12).

The UN High Commissioner on Human Rights Michelle Bachelet said on June 21 that she hoped to agree on terms for a visit to Xinjiang to investigate human rights abuses before the end of the year, laying out an explicit deadline for the first time since negotiations began in September 2018. A Chinese spokesperson warned that Bachelet should not make “erroneous remarks” about the alleged human rights abuses, which China has consistently denied (Reuters, June 21). At a foreign ministry press briefing, spokesperson Zhao Lijian said that China welcomes the High Commissioner for “a friendly visit with the purpose of promoting exchanges and cooperation, but not a “so-called ‘investigation’ with presumption of guilt,” and that it remains opposed to “anyone using this issue for political manipulation and to exert pressure on China” (PRC MFA, June 22).

Alongside the semi-annual escalating exchanges on human rights, Chinese diplomats have also increasingly engaged in blatant whataboutism to distract from criticisms, echoed by state media. In one example of the genre, a Global Times report complained that the UK, U.S. and Canada were a “cartel of killers” hypocritically whipping up global “hysteria” on Xinjiang despite having committed human rights violations themselves (Global Times, June 20).

How China Subverts Human Rights Norms at the United Nations

Since Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping took power in 2012, China has substantially increased its financial and peacekeeping contributions to the UN, although its overall contributions remain a distant second to the U.S. According to Jeffrey Feltman, a former UN under-secretary-general for political affairs, China has more recently increased the use of its UN Security Council veto power, “downplaying human rights norms, playing up sovereign rights, and vexing the United States”—often in tactical coordination with Russia (Brookings, September 14, 2020). China has generally worked to increase its influence on developing issues such as technology standards, climate change, healthcare and agriculture.[4] It has also sought to reform the standard concept of multilateralism to privilege states’ sovereign rights, promoting itself as a leader against “Western hegemony” for the developing world, and argued for a narrow definition of human rights that seeks to absolve states of the responsibility to protect citizens’ freedoms.

The watchdog group Human Rights Watch argues that since China first proposed a so-called “win-win” (合作共赢, hezuo gongying) resolution on human rights at the UNHRC in 2018 (PRC Permanent Mission to the UN, March 1, 2018), it has waged a steady campaign of “slowly undermining norms through established procedures and rhetoric, which have had significant consequences on accountability for human rights violations” (Human Rights Watch, September 14, 2020).

An updated resolution to promote “mutually beneficial cooperation” (互利合作, huli hezuo) in the field of human rights, which appeared to reframe the human rights conversation around dialogue and cooperation instead of accountability, was adopted by the UNHRC in June 2020 (Xinhua, June 23, 2020). Although such resolutions may seem abstract, once passed by the UN they lend critical legitimacy to Chinese leaders’ statements that the PRC has made “historic and pioneering contributions to the development of multilateralism theory” and offered uniquely Chinese solutions for the “building of a community with a shared future for mankind” that are “practicable for most developing countries” (People’s Daily, February 21; Global Times, June 24). This past March, China once again proposed a resolution on “mutually beneficial cooperation” at the UNHRC (Xinhua, March 24).

Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy in the New Era

Propaganda celebrating the PRC’s diplomacy “with Chinese characteristics” has been abundant in the lead up to the CCP’s centennial. In late June, the PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Central Propaganda Department jointly unveiled a new website dedicated to promoting “Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy and Chinese Diplomacy in the New Era” (习近平外交思想和新时代中国外交, Xi Jinping waijiao sixiang he xin shidai zhongguo waijiao). In addition to serving as a repository of diplomacy-related quotes and speeches from Xi, many articles archived on the site stress maintaining the CCP’s role as the core of China’s foreign relations work and promoting “major-power diplomacy” to realize the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” (chinadiplomacy.org.cn, accessed July 1). A press release summarized additional goals (more palatable to foreign audiences): “safeguard national sovereignty, security, and development interests, and build a network of partnerships around the world,” and use the BRI as a platform for the “reform and construction of the global governance system and the building of a community with a shared future for mankind” (Chinanews.com, June 30).

A recent speech by Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the Lanting Forum, titled “A New Journey Ahead After 50 Extraordinary Years,” marked highlights in China’s cooperation with the UN since the UNGA shifted its official recognition from Taiwan to China in October 1971. Wang focused on the positives, noting China’s commitment to “upholding the international system with the UN at its core” and stating that “China has shared its wisdom and solution [sic] for world peace and development at every historical moment” (PRC MFA, June 25). Xi Jinping’s July 1 remarks on the anniversary of the CCP centennial were a little harsher on the topic of foreign relations. During an hour-long speech that mostly celebrated the ruling CCP’s achievements, Xi also warned that “the Chinese people will never allow any foreign forces to bully, oppress, or enslave us. Whoever wants to do so will surely break their heads and bleed against the Great Wall of steel built from the blood and flesh of more than 1.4 billion Chinese people” (Xinhua, July 1).

Conclusion

The diplomatic war over China’s human rights policies at the UN demonstrates the growing strain between China’s efforts to present itself as a benign, positive partner for global development and an increasingly strident and nationalistic diplomacy that more closely aligns with Xi’s policy priorities to centralize power and promote China as a rising superpower (South China Morning Post, June 27).

Amid such “wolf warrior” diplomacy, China’s propaganda narratives of international cooperation remain ineffective abroad. A June 30 Pew Research Center poll found that large majorities across advanced economies believe that China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people (Pew Research Center, June 30). Observers might extrapolate that the PRC has similarly little respect for the universal freedoms enshrined in the UN Human Rights Charter. Instead, Chinese diplomats have proven adroit at undermining and reinterpreting long-standing norms on human rights and multilateralism. Under Xi, the PRC has grown bold in pursuing its security-focused developmental goals, with only the lightest veneer of presenting a more “loveable” image to the world (Xinhua, June 1; Nikkei Asia, June 10).

Elizabeth Chen is the editor of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, feel free to reach out to her at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] Countries can add their names to statements or resolutions up to two weeks after the end of a UNHRC session, with the current session scheduled to run until July 13. Although the author was unable to find a full list of the signatories to the Belarus statement, which has not been published as of the time of writing, they reportedly included Belarus, Iran, North Korea, Russia, Sri Lanka, Syria and Venezuela (Aljazeera, June 22).

[2] Note, for example, that Turkey, which is marked orange on the October 2020 map, has since come out with several official statements supporting a UN investigation in Xinjiang (Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, October 6, 2020). But it has also cracked down on Uyghur diaspora members that criticize China at home, and the government has not made a definitive statement condemning China’s detention of Muslim minorities in Xinjiang (Uyghur Human Rights Project, June 24), demonstrating the difficulty that developing nations face in taking a stance on the Xinjiang issue.

[3] Western media reported that Chinese diplomats had sent notes to many of the UN’s 193 member states in the lead up to the event, urging them not to participate in the “anti-China event” (AP, May 12).

[4] Specifically, Kristine Lee has described how China has leveraged UN initiatives such as the Sustainable Development Goals to promote its Belt and Road Initiative; institutionalize cyber-sovereignty norms that restrict the free flow of information; and used its leadership of specific agencies to ostracize Taiwan (USCC, June 24, 2020).