A New Chinese National Security Bureaucracy Emerges

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 23

By:

Introduction

An intriguing aspect of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s political consolidation was the establishment of a Central National Security Commission (CNSC; 中央国家安全委员会, Zhongyang guojia anquan weiyuanhui ) at the end of 2013. The CNSC seemingly empowered Xi, who was put in charge of the new body, and through a permanent staff structure, perhaps set the stage for more effective strategic planning and crisis response [1]. Over the last few years, subordinate National Security Commissions (NSCs) have been installed at all tiers of the party structure down to the county level. The CNSC thus sits atop a new organizational hierarchy that strengthens Xi’s ability to set the agenda and improves the party’s ability to coordinate national security affairs. While the system’s political utility for Xi is clear, its role in improving crisis response at the local level could be constrained by several factors.

Revisiting the CNSC

The CNSC fits into a larger construct known as the “national security system” (国家安全体系, Guojia anquan tixi) that has been developed during the Xi era to protect the party from domestic and foreign threats. The ideational core of the system is the “holistic national security concept” (总体国家安全观, zongti guojia anquan guan) that Xi outlined at the first CNSC meeting in April 2014 (Xinhua, 2014). The concept’s key characteristic is that the party cannot think of security in narrow, traditional terms (China Brief, 2015). Rather, the concept must be defined more broadly to encompass diverse areas such as cybersecurity, biosecurity, energy security, and counterterrorism, many of which involve interactions between domestic security and the outside world—Xi mentioned 11 areas in total. Other changes complemented the implementation of this emerging security system, including reforms to the People’s Armed Police (PAP), new laws on espionage, NGOs, and cybersecurity [2], and a formal “national security strategy” (国家安全战略, Guojia anquan zhanlüe). In November 2021, the Politburo deliberated the second such “strategy,” which will cover 2021-2015; an earlier document was approved in 2015 (Xinhua, 2021).

As the organizational face of the “national security system,” the CNSC was intended to improve high-level coordination of national security work. In the past, excessive bureaucratic stove-piping and limited information sharing constrained strategic planning and crisis response [3]. The CNSC would alleviate those problems by ensuring the involvement of Xi, who could presumably compel the bureaucracy to cooperate. This was accompanied by the establishment of a permanent CNSC staff in the Central Committee General Office, which is led by a top party official (previously Li Zhanshu and now Ding Xuexiang; the current deputy head has been reported as Minister of State Security Chen Wenqing) (The Paper, May 7). The staff also included representatives from civilian ministries and the military. The CNSC would thus be more cohesive than a previous ad-hoc National Security Leading Small Group set up in 2000 under Jiang Zemin [4].

The 19th Party Congress in October 2017 laid the basis for further developments by writing the “holistic national security concept” into the party’s platform and granting Xi another five-year term as party general-secretary (Xinhua, 2017). In April 2018, Xi once again addressed the CNSC, stating that the body had become the “main framework for the national security system” and a “coordination mechanism for national security work” under the party’s leadership (Xinhua, 2018). In a sign of impending changes, Xi also cited new regulations that “clarified the main responsibilities of party committees at all levels to strengthen supervision and inspection… to ensure that the central party’s decisions on national security work have been implemented” (Xinhua, 2018).

A Proliferation of NSCs

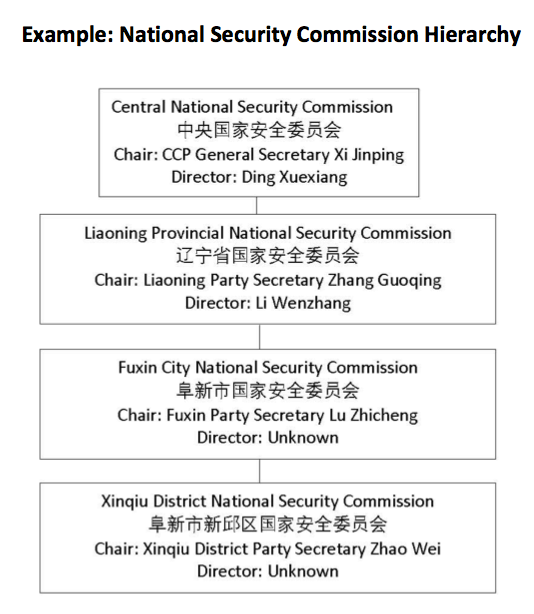

Xi’s invocation of “party committees at all levels” raised the question of how lower tiers of the party hierarchy would fit into the “national security system.” Answers came in early 2019 when subordinate NSCs began to appear throughout the party structure—provinces, prefectures, municipalities, city districts, and counties now all have NSCs within their party committees, forming a vertical system culminating in the CNSC (see example below).

Some details on the broader NSC system have come to light. Mirroring the CNSC, the lower level NSCs are chaired by the relevant party committee secretary, with deputy party secretaries (one of whom also serves as state administrative leader, such as governor or mayor) serving as NSC vice chairs. These officials sit on an NSC standing committee (常务委员会, Changwu weiyuanhui) while others are NSC “members” (委员, weiyuan). Like the CNSC, lower level NSCs are managed by “offices” (办公室, bangongshi) led by a director and deputy director. The NSC offices are one of several supporting the party committees, alongside foreign affairs, cyber security, military-civilian fusion, economic reform, and other offices, but NSC offices are unique in that they are located within the party committee general offices (办公厅, bangongting)[5]. This puts NSC offices at the center of the daily management of party affairs and underscoring the sensitivity of their duties [6].

Information from the provincial party committees suggests that the NSCs are meant to serve as “discussion and coordination organs” (议事协调结构, yishi jietao jiegou), replacing existing “national security leading small groups” (国家安全工作领导小组, guojia anquan gongzuo lingdao xiaozu) (information from the Shanxi provincial party committee is available at Shanxi Daily, October 29, 2018; information from the Anhui committee is at Discipline, Inspection and Supervision of Anhui). In order to facilitate discussion, the NSCs hold plenary meetings that are frequently publicized in local media. The first provincial plenaries were convened in March 2019, with city and county-level meetings held several months later. By February 2021, the Hunan provincial NSC had held its fourth plenum, indicating that these meetings occur about one or two times per year (Hunan Government, 2021). The timing indicates that CNSC plenaries take place first (with at least four having taken place since the 19th Party Congress, but only one that has been publicized), followed by provincial plenaries, and then lower-level meetings, each informing the agenda for the next session.

Political themes are a consistent feature of these plenums. Areas of focus include studying Xi’s speeches, such as his comments to recent Politburo study sessions focused on national security and his speeches to CNSC meetings; strengthening the “party’s centralized and unified leadership” over national security work (党对国家安全工作的集中统一领导, Dang dui guojia anquan gongzuo de jizhong tongyi lingdao); and, following the 19th Party Congress Work Report, emphasizing ideas such as the “holistic national security concept” and “political security” as a “fundamental task” for national security work at all levels (Xinhua, December 12, 2020; Jilin Ribao, April 24; Yunnan.cn, April 15). The NSCs thus reinforce Xi’s status at the apex of the system, guarantee that the central party’s priorities and views on the security environment are widely understood, and highlight the message that the party must ensure its own security, including through close supervision of security organs at all levels.

The plenums also allow leaders to discuss practical challenges. The span of issues covered in these meetings reflects the breadth of the “holistic national security concept,” including topics such as epidemic control, supply chain security, financial security (including government debt), industrial safety, network security, energy security, and preparations for major events, such as the Spring Festival or the party centennial. As noted in a Wenzhou City NSC meeting, the intent is to manage challenges so that “small things do not get out of the villages and big things do not get out of the townships” (小事不出村、大事不出镇, xiaoshi bu chu cun, dashi bu chu zhen) (Wenzhou Government, 2021). In some cases, the agenda also reflects local priorities, as with the Yunnan NSC’s discussions of cross-border criminal activity (Yunnan.cn, 2020).

How the lower-tier NSCs enhance coordination is less certain. At a minimum, the plenums provide opportunities for party leaders to listen to reports from national security-related party and state departments (though participant lists are typically not publicized) [7]. In April 2021, municipal NSC offices were also identified as working with other bureaucracies to implement National Security Education Days (国家安全教育日, guojia anquan jiaoyu ri), in one case involving education for party cadres and mass propaganda directed at the public (Government of Jincheng City, Shanxi, 2021). The NSC offices also likely schedule ad-hoc meetings for party leaders on national security issues and manage the flow of information to party leaders and to higher and lower level NSCs.

Complications

Installing new NSCs throughout the party structure helps strengthen central supervision, but does not grant local party officials more power or flexibility to respond to crises. Party committees do not supervise military and paramilitary forces, which often play a critical role in domestic emergency response. Moreover, large-scale crises are sometimes handled at the national level. For instance, the military took the lead in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake and the July 2021 Zhengzhou flooding. Indeed, in December 2017, the party rescinded the ability of local officials to mobilize PAP units without securing permission from central authorities (Sina, 2017). Nevertheless, NSCs could still make a modest contribution to more effective crisis management by facilitating discussions between the party, military, and state departments. For instance, in July 2021, the Tibetan Military District commander participated in a Tibetan Autonomous Region NSC meeting which, among other things, touched on border security and social stability (Coqen County Government, 2021).

Crisis response remains primarily a function of the state, not the party or the NSC system. A 2018 State Council reform established a new Ministry of Emergency Management to consolidate various emergency response forces (Xinhua, 2018). China’s emergency response plans (应急预算, Yingji yusuan), many of which were updated in 2020 and 2021, suggest that local emergency management departments play a key role in handling different contingencies, such as fires, earthquakes, industrial accidents, and internal unrest [8]. For instance, Jiangxi province’s 2020 emergency plan for sudden geological disasters references an emergency command organ facilitated by the provincial emergency management office (江西应急厅, Jiangxi yingji ting) but says nothing of the provincial NSC (Jiangxi Government, 2020). Hence, the party may have strengthened its oversight, but the state continues to plan and execute national security work.

Finally, deference to the center could inhibit local initiative. The content of provincial and lower NSC plenaries suggests that party leaders look to Xi and the central party through the CNSC for guidance on what they should be doing and thinking. This engenders familiarity with national priorities throughout the party structure, but is less likely to lead to local officials using the NSCs to develop innovative solutions to vexing problems. It is possible that the NSCs could devolve into another forum focused on demonstrating fealty to Xi with little of practical value accomplished.

Conclusion

China’s CNSC is not a standalone body like the U.S. National Security Council, but rather the highest echelon in a nationwide system that includes subordinate NSCs down to the county level. This supports an interpretation of the CNSC as an inward-looking body primarily focused on supervising management of domestic security [9]. The creation of an NSC system within the party’s organizational structure reinforces Xi’s dominance of the national security architecture and creates new mechanisms for information sharing and coordination within the party. Yet it is unclear that the NSCs will promote more effective crisis response by local party committees. This is because local leaders lack control of key assets, emergency planning is handled by the state, and incentives for local initiative appear low. For now, the “national security system” is a fruitful avenue for further research and deserves to be more fully analyzed as China’s leaders prepare for next year’s 20th Party Congress.

Dr. Joel Wuthnow is a senior research fellow in the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs at the U.S. National Defense University. This piece reflects only the author’s views and not those of the National Defense University, Department of Defense, or U.S. government.

Notes

[1] See Joel Wuthnow, “China’s New ‘Black Box’: Prospects for the Central National Security Commission,” China Quarterly 232 (2017), 886-903; David M. Lampton, “Xi Jinping and the National Security Commission: Policy Coordination and Political Power,” Journal of Contemporary China 24:95 (2015), 759-777; and You Ji, “China’s National Security Commission: Theory, Evolution, and Operations,” Journal of Contemporary China 25:98 (2016), 178-196.

[2] For recent analysis of the “national security system,” see Tai Ming Cheung, “The Chinese National Security State Emerges from the Shadows to Center Stage,” China Leadership Monitor, September 1, 2020, https://www.prcleader.org/cheung; and Sheena Chestnut Greitens, “Domestic Security in China under Xi Jinping,” China Leadership Monitor, March 1, 2019, https://www.prcleader.org/greitens.

[3] Wuthnow, “China’s New ‘Black Box’”; and Andrew S. Erickson and Adam P. Liff, “Installing a Safety on the ‘Loaded Gun’? China’s Institutional Reforms, National Security Commission, and Sino-Japanese Crisis (In)Stability,” Journal of Contemporary China 25:98 (2016), 197-215.

[4] The National Security Leading Small Group had the same membership as an older Foreign Affairs Leading Small Group. This latter group continued to exist following the creation of the CNSC until it was replaced by a Central Foreign Affairs Work Commission in 2018.

[5] See, for example, the list of Party organs in the Henan provincial party committee structure: https://www.hasbb.gov.cn/sitesources/hnsbb/page_pc/sdgd/hnswbmjg/list1.html . Most references to the provincial national security LSGs dates from 2017-2018, though there are sporadic references back to 2006.

[6] It appears that the General Office directors serve concurrently as NSC office director. Ding Xuexing plays this role at the CNSC level.

[7] For instance, the Wenzhou City NSC’s June 2021 plenary featured reports from the municipal political and legal affairs commission, network information office, and municipal health commission. https://www.wenzhou.gov.cn/art/2021/6/17/art_1217828_59052738.html.

[8] For background on these plans, see Catherine Welch, “Civilian Authorities and Contingency Planning in China,” in Andrew Scobell et al., eds., The People’s Liberation Army and Contingency Planning in China (Washington, DC: NDU Press, 2015), 85-106.

[9] For an excellent analysis, Sheena Chestnut Greitens, “Prepared Testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee,” June 8, 2021, 1-4.