Briefs

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 7

By:

Is Myanmar’s Military Junta Quashing the Insurgency Through Domestic Crackdowns and Regional Outreach?

Jacob Zenn

Since Myanmar’s February 2021 military coup to overturn the democratically elected victory of Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the junta has experienced widespread resistance from multiple regions of the country (mmtimes.com, February 4, 2021). However, the military appears to be succeeding on the regional front in avoiding sanctions and receiving legitimacy. For example, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) current chair, Cambodia, hosted Myanmar’s military generals for discussions with ASEAN intelligence officers about the establishment of an ASEAN Military Intelligence Community (irrawaddy.com, March 18).This occurred at the 19th ASEAN Military Intelligence Meeting (AMIM-19) held on March 17 and indicated Myanmar was not an “outcast” in ASEAN, despite its military crackdown on protesters and regional and ethnic militias that oppose military rule.

This meeting in Cambodia marked a change in ASEAN’s position towards Myanmar’s military rulers. The junta leader Min Aung Hlaing was banned from the annual summit of ASEAN leaders in October 2021 and all Myanmar military junta representatives were banned from attending the summit of ASEAN foreign ministers held as recently as in February 2022 (mizzima.com, March 17). It is probable that at least military and intelligence officials in ASEAN are more open to working with the junta than other diplomats in the region.

Another key regional backer of the military junta is China. Beijing appears to welcome Myanmar’s declining international status because it forces Myanmar to become closer to China (irrawaddy.com, March 16). In contrast, during Myanmar’s democratic opening its diplomatic relations with the West were steadily improving, especially when then secretary of state Hillary R. Clinton visited the country (amnesty.org, November 29, 2011). Despite growing closer, since taking power, the military junta has sought to limit its reliance on China by buying Russian arms for their counter-insurgency operations. As Russia continues its war in Ukraine, however, this is set to change and may force Myanmar into a closer military relationship with China (asia.nikkei.com, February 9, 2021). Beijing may also benefit from Myanmar’s walk-back on democratization because it means China itself is less likely to become an isolated non-democracy in an otherwise democratizing Southeast and East Asian region.

On the domestic front, Myanmar is not only suppressing the militias’ insurgency through force of arms, but is also taking over the judicial system. Instead of trying opponents of the junta who have gone on strike in the regular courts, for example, the junta has set up military tribunals in prisons. This assures such protesters will be prosecuted and convicted in prison and be unable to continue their resistance to the junta. Lawyers, moreover, have not been allowed access to the prisoners to defend them (frontiermyanmar.net, March 17).

Lastly, the junta is taking the unusual step of soliciting support from nationalist Buddhist monks and also training these monks in how to use firearms. These “military-backed monks,” however, are not necessarily local to the villages where they are placed, but brought to different areas of the country by the military (rfa.org, March 14). Even though these monks may not, therefore, receive local support, the military’s exploitation of monks as well as of the judicial system reflects how the junta is broadening its counter-insurgency beyond the military focus. After more than one year of conflict, there appears to be no end in sight to the fighting, but the junta, to the chagrin of much of the international community and numerous citizens in Myanmar, appears to be shoring up its hold on the country, politically and militarily.

*****

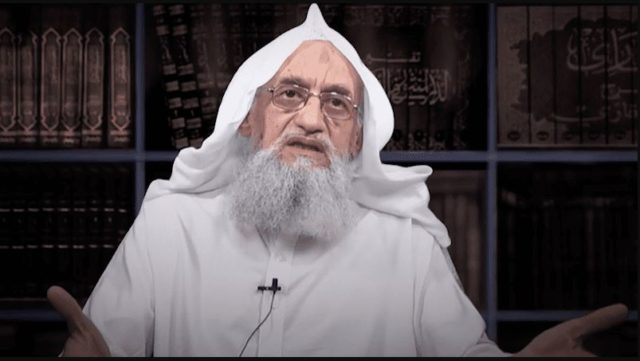

Aymen Al-Zawahiri Speech Fails to Counter Islamic State’s New Caliph Announcement

Jacob Zenn

Less than two weeks after Islamic State’s (IS) March 10 announcement of its new caliph, Abu Hassan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi, al-Qaeda’s leader, Aymen al-Zawahiri, released a new audio speech (alarabiya.net, March 10). Unlike the significant attention given to IS’s caliph announcement in both mainstream media and IS propaganda outlets, al-Zawahiri’s speech went under the radar, with little mainstream or jihadist attention to it. This contrast demonstrates that while al-Zawahiri is alive and remains al-Qaeda’s leader, he lacks the charisma to galvanize jihadists’ attention towards al-Qaeda even while IS’s own leadership has been in turmoil and transition.

Al-Zawahiri’s speech appears to lack any mention of current events, so it was unclear whether the video was current or recorded several months earlier. The purpose of the video was dawa (proselytization) and he discussed the history of Islam, challenged the theories of atheism, communism and capitalism, promoted the righteousness of Islam, and mentioned thinkers ranging from Malcolm X to Egyptian academic, Abdel Wahab El-Messiri, who were notably not jihadists (Twitter/@minaallami, March 21). His avoidance of an explicitly jihadist tone comes at the same time the most successful al-Qaeda-allied group, the Taliban, is distancing itself from overt jihadism. This suggests that al-Qaeda and its allies’ future success may depend on minimizing the violent rhetoric of al-Qaeda’s past and focusing more on diplomacy and intellectualism.

Such an approach has already been employed by the formerly al-Qaeda-allied Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in northeastern Syria, which now is officially organizationally separately from al-Qaeda (mei.edu, June 24, 2021). It has attempted to appear as a ‘normal,’ albeit authoritarian, state actor in areas that it controls in Syria. Al-Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate, Group for Supporters of Islam and Muslims (JNIM), still engages in asymmetric warfare, but has tended to avoid attacks specifically on foreign interests, except for on mines and kidnappings, and remains open to negotiations for autonomous jihadist rule and is loyal to the Taliban (aljazeera.com, October 19, 2021). JNIM could possibly follow the Taliban and HTS path in the future.

In contrast to the unheralded video from al-Zawahiri, IS’s announcement of the new “caliph” received great fanfare from all of IS’s provinces, which, in turn, led to widespread international media reporting on it (Telegram, March 14). Nevertheless, Abu Hassan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi himself is unable to be any more of a “public” figure than al-Zawahiri because, as the announcement of his appointment indicated, security reasons necessitate his remaining in hiding. Thus, although his becoming “caliph” inspired IS provinces more than al-Zawahiri’s video inspired al-Qaeda affiliates, it does not appear that either of these leaders will dramatically influence the operations of either group.

Further, it is speculated that IS’s new caliph may have obtained his position amid internal divisions with IS (aawsat.com, March 2). This could make it more difficult for him to unite IS at a time when it is no longer holding territory in the heartland of Iraq and Syria. It may require a highly skilled leader to keep IS fighter morale high, and it remains to be seen whether Abu Hassan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi will become such a leader.

At the organizational level, however, it appears he may already be having an impact. For example, Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP), which previously included Nigeria-based “Boko Haram” and Sahel-based “Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS),” for the first time is now claiming attacks in the name of “ISWAP” and a separate new “Islamic State in Sahel Province,” the latter referring to what previously was ISGS (Twitter/@SimNasr, March 23). Evidence suggests the two groups had virtually no overlap and that this will result in more provinces statistically existing under the new caliph’s leadership. Moreover, IS’s renewed focus on attacking Israel could also reflect the new caliph’s strategy (jpost.com, March 28).