China’s Shifting Approach to Alliance Politics

Publication: China Brief Volume: 22 Issue: 13

By:

For decades, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has abstained from seeking formal alliances. Chinese leaders often invoke the principle of advancing state-to-state relations through “dialogue rather than confrontation [and] partnerships rather than alliances” (对话不对抗、结伴不结盟, duihua bu duikang, jieban bu jiemeng) (Xinhuanet, June 23; Gov.cn, November 22, 2021). The PRC highlights its multitude of strategic partnerships and lack of official alliances as emblematic of its self-proclaimed anti-hegemonic approach to international relations, which is predicated on inclusivity, mutual respect and “win-win cooperation.” Chinese Communist Party (CCP) propaganda regularly juxtaposes this purportedly positive-sum approach to world politics with its stock depiction of the United States as a decaying but violent empire, which practices a ruthless brand of power politics based on zero-sum thinking. For the CCP, America’s “cold war mentality” manifests in its global military presence and formal security alliances in Europe and Asia, which Beijing characterizes as “closed and exclusive cliques” (PRC Foreign Ministry [FMPRC], April 12; China Brief, October 22, 2021).

Under President Xi Jinping, the PRC has gone beyond promoting virtues such as inclusivity, dialogue, mutual respect, peace-building and common development in world politics as a kind of rhetorical armor against Western criticism, and has begun to invoke these principles to justify its efforts to reshape the existing international order. The blueprint for these efforts is Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy, which sets forth achieving a “community with a shared future for mankind” through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and other programs as a central goal (People’s Daily, May 16). Beijing’s efforts to develop new multilateral institutions were originally economic and diplomatic in nature, but the PRC has now begun to position itself as a global security leader. This spring, Xi announced the launch of a new Global Security Initiative (China Brief, May 13). At the recent BRICS leaders’ virtual summit, Xi stated that the initiative is a response to unprecedented international instability and insecurity, which he primarily blamed on “some countries,” i.e. the U.S. and its allies, “seeking absolute security, coercing other countries to choose sides and fostering confrontation between blocs, and ignoring the rights and interests of other countries” (People.cn, June 29). Indeed, Beijing has evinced growing concern that in the Indo-Pacific region the U.S. and its allies are moving from a “hub and spokes” model of bilateral security alliances to a collective security system.

Clearly, the emergence of a collective security organization in the Indo-Pacific region, akin to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Europe, would impede the PRC’s quest to achieve a more Sinocentric order in Asia and beyond. Would an “Asian NATO” drive China to break from its longstanding aversion to formal alliances? Any tangible benefits such security pacts might provide to Beijing would need to be weighed against the potential normative costs of abandoning a longstanding operating principle of PRC foreign policy. As a result, China will likely continue to deepen its ties with close strategic partners, developing relationships that are alliances in all but name.

Beijing’s NATO Fixation

In the CCP’s official narrative, the U.S. is a declining but militaristic hegemon, which cloaks its Machiavellian actions in high-sounding, liberal rhetoric. State media regularly depict U.S. ally and partner networks as enablers of Washington’s addiction to hegemony (Guangming ribao, May 2). This narrative has recently become even more pronounced as the PRC seeks to frame the Russia-Ukraine War primarily as a consequence of U.S. power politics— especially Washington’s backing of NATO’s post-Cold War eastward expansion. The constant criticisms of NATO serve to reconcile the contradiction between Beijing’s claims to an altruistic foreign policy and its entente with Moscow, which has remained close throughout Russia’s unprovoked war of aggression against Ukraine. However, another key driver of the PRC’s heightened criticism of NATO is growing anxiety about the Transatlantic security grouping’s increasing focus and engagement with the Asia-Pacific region. Beijing’s greatest fear may be that in the aftermath of the Ukraine invasion, the U.S. and its Indo-Pacific allies will come to see NATO as a model for the development of a new, U.S-led collective security organization in Asia. As a result, although Beijing has traditionally viewed NATO as primarily an actor in Europe and its periphery, the PRC is now increasingly fixated on the Transatlantic alliance’s shifting approach to the Indo-Pacific region (China Brief, April 29).

At the Madrid summit in late June, NATO adopted a new Strategic Concept, which declares that the PRC’s “stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests, security and values” and criticizes the deepening Russia-China partnership for “mutually reinforcing attempts to undercut the rules-based international order” (NATO, June 29). In addition to explicitly identifying China as a threat, the new Strategic Concept also directs NATO to enhance “cooperation with new and existing partners in the Indo-Pacific to tackle cross-regional challenges and shared security interests.” In a signal to Beijing that progress on this front is already well underway, the leaders of Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, all joined the Madrid meetings, the first time that leaders from the Indo-Pacific region have participated in a NATO summit (NATO, June 29).

The PRC’s official retort to the Madrid summit has been caustic. In response to NATO’s increasing focus on China, the People’s Daily published an editorial under its “Voice of China” (钟声, zhongsheng) byline, which denotes an authoritative perspective, entitled: “NATO is a Systemic Challenge to Global security and stability” (People’s Daily, July 5). The piece notes that NATO mentioning China in its Strategic Concept for the first time is a direct consequence of U.S. intimidation of other member states, and exemplifies Washington’s growing reliance on the bloc to maintain hegemony and instigate a new Cold War. The editorial not only censures the Madrid Summit for its “escalation and exaggeration” of the ‘China Challenge,’” it also criticizes the meeting for deliberately attracting U.S. allies from the Indo-Pacific region. As a result of NATO’s designation of the PRC as a strategic competitor, the article posits that China has no choice but to respond forcefully in order to safeguard its interests and sovereignty.

Security Guarantees from Beijing?

If the PRC’s international ambitions were more circumscribed, its lack of alliances would be a minor issue. However, it will be very challenging for the PRC to achieve Xi’s expansive foreign policy vision in an Indo-Pacific strategic environment where most of the other major powers are aligned with U.S., and where many middle powers and small states cling to nonalignment. In other words, most of the countries in the region are either cooperating with the U.S. in seeking to balance China, or hedging as they await further clarity on the outcome of the U.S.-China strategic competition. In order for China to improve its position through diplomacy, Beijing must repair its regional relationships and gain the trust of its neighbors.

The conventional view among Chinese experts is that the principle of “partnerships rather than alliances” reassures neighbors as it demonstrates that the PRC is not driven by old-fashioned realpolitik. For example, in a lengthy 2019 People’s Daily feature on why Chinese diplomacy centers on partnerships over alliances, Su Changhe, an international relations scholar at Fudan University, stated that the difference between an alliance and a partnership is that the former approach is based on the “old international relations thinking of finding enemies,” whereas the latter way epitomizes a new kind of global politics that is focused on “making friends” (People.cn, November 16. 2019). However, some of the PRC’s leading international relations experts are reconsidering these long-held assumptions. In a recent interview with Phoenix TV, Tsinghua University Professor Yan Xuetong argued that China could gain the trust of its neighbors by providing them with “security guarantees” (安全保障, anquan baozhang) (iFeng news, May 9). According to Yan, moving away from ambiguity is essential to reassuring neighbors concerned about China’s growing military strength. He reasons that if the PRC, which is now the world’s second strongest military power, “does not give other states security guarantees, they are bound to ask, what do you want with all these weapons? What are you doing?”

Selective Criticism

In addition to its recent criticism of NATO, Beijing also continues to strongly reproach regional security multilaterals in the Indo-Pacific that involve the U.S., particularly the QUAD and AUKUS, as well as some of the U.S. bilateral alliances in the region, particularly those with Japan, South Korea and Australia. For example, state media regularly charges that the U.S.-Japan alliance incubates Japanese militarism, and threatens the peace in Asia (Global Times, March 10; Huanqiu, May 17, 2021). Nevertheless, the PRC’s criticisms of U.S. alliance relationships in Asia are selective. For example, both Thailand and Pakistan remain formal U.S. allies, but the PRC refrains from criticizing these relationships because Bangkok and Islamabad are each closer to Beijing than they are to Washington (U.S. Department of State, January 20, 2021). This underscores that the PRC does not criticize its neighbors for being American allies per se, but rather chastises them for being active partners of the U.S.

Despite its oft-stated aversion to alliances, China has a Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance with North Korea, a security pact that obligates the two countries to aid each other against attack by a foreign power (38 North, June 30, 2021). The treaty, originally signed in 1961, is subject to renewal by both parties every twenty years. Last year, a Japanese journalist asked Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin whether the treaty would be extended, particularly given the profound global changes that have occurred since its inception. Wang responded that the treaty “remains in force unless agreement is reached on its amendment or termination,” and continues to promote “peace, stability, development and prosperity in the region and beyond” (FMPRC, July 7, 2021). It is tempting to view the China-North Korea defense treaty as a Cold War relic. However, the endurance of the treaty, despite China’s frustration with North Korea’s nuclear development, highlights that the alliance still retains immense strategic value to Beijing. As the treaty has been in effect for six decades, a decision not to renew it, would amount to a major downgrade in relations, which is an unacceptable risk for Beijing given North Korea’s salience as a buffer state separating China from Japan, South Korea, and the U.S. military presence in Northeast Asia.

Conclusion

Over the past several decades, China’s behavior as an international security actor has often defied the predictions of experts. Long-standing presuppositions, for example- that China would never deploy combat forces abroad or establish military bases overseas, have not been borne out. Is the belief that the PRC will never seek official alliances, the next of the “China will never” assumptions to fall by the wayside?

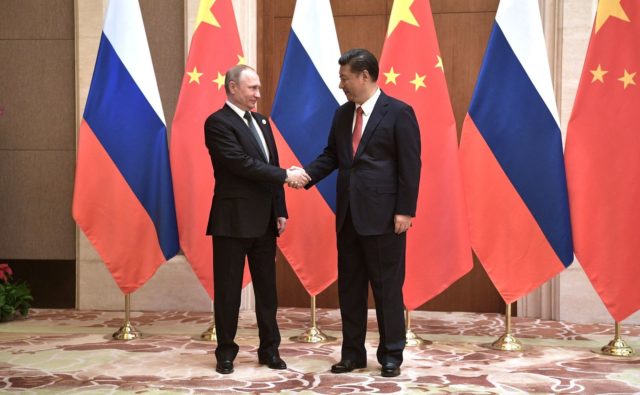

Time will tell, but at present the benefits to the PRC of designating a close partner like Pakistan or Russia an official ally do not outweigh the costs. For example, even as China and Russia have grown steadily closer, PRC officials have taken much greater pains than their counterparts in the Kremlin to stress that the relationship is not an alliance, but a close strategic partnership (FMPRC, March 7). Furthermore, the PRC has little reason to upgrade ties with aligned states such as Russia or Pakistan because it already enjoys close relationships with Moscow and Islamabad that are tantamount to de facto alliances. However, the promise of official defense treaties or security guarantees could be useful for China’s efforts to reassure and potentially secure basing access in smaller neighboring countries in Asia and Africa.

John S. Van Oudenaren is Editor-in-Chief of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, please reach out to him at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.