Beijing Makes a Big Long-term Bet on Nuclear Power

Publication: China Brief Volume: 22 Issue: 15

By:

Last fall, China suffered extensive power outages due to a combination of surging electricity demand and tight supply. A confluence of factors contributed to the energy supply shortage, but nearly all traced back to China’s struggle to manage its overdependence on coal for power generation: rising global coal prices; shuttering of old power plants as part of a push to enhance energy efficiency; emission-reduction efforts; an “unofficial” embargo on Australian coal imports due to geopolitical strife between Beijing and Canberra; and disparities in government price controls (power plants must purchase coal at market rates, but consumer prices are set in a narrow band) that incentivized plants to cease or slow operations rather than produce electricity at a financial loss (Caixin, October 12, 2021; Zaobao, July 14). In 2022, China has avoided a replay of last year’s energy crunch despite the supply shocks in the energy markets induced by the Ukraine conflict by increasing domestic coal production, exploiting the opportunity to import Russian oil and coal at discounted rates and continuing to steadily increase its renewable energy capacity. Boosting domestic coal production has been particularly essential to meet demand. This month, the National Energy Administration (NEA) reported that during the second quarter, China’s raw coal output rose 10 percent year-on-year, which the NEA highlighted as particularly noteworthy given it came on the basis of 16 percent growth in coal output in the same quarter last year (NEA, August 2). Another mitigating factor for China on the energy front has been heavy spring rainfall in many areas of the country that has increased hydropower output over 20 percent in the first half of this year—a substantial boost as hydroelectricity already accounts for about 15 percent of China’s overall energy mix (NEA, August 2; Global Times, May 5).

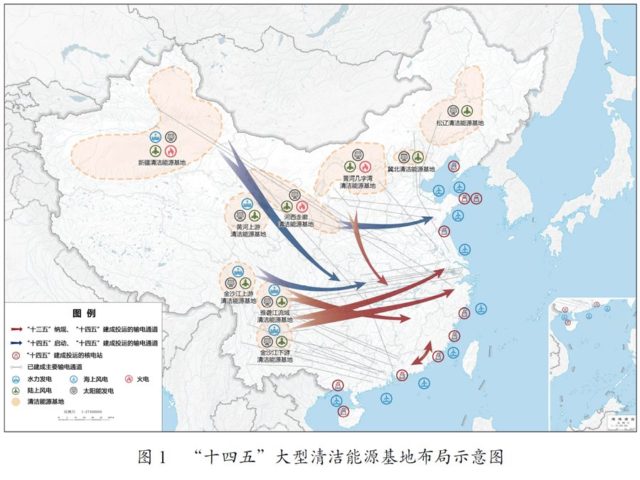

Increasing domestic coal extraction and power generation has helped Beijing to shore up supply and boost its energy security. However, falling back on coal threatens the ambitious climate agenda laid out by General Secretary Xi Jinping, which is for China to achieve the sequential “double carbon” (双碳, shuangtan) objectives of reaching peak carbon use by 2030 and attaining carbon neutrality by 2060 (People.cn, May 23). The People’s Republic of China has long expressed hope that its civilian nuclear energy program can provide a cost-effective and low carbon footprint means for China to address its energy challenges. The 14th Five-year Plan stipulates the development of a “modern energy system” by developing large clean energy bases and constructing a network of coastal nuclear power plants to increase the non-fossil fuel share of China’ energy consumption to 20 percent by 2035 (Xinhuanet, May 13, 2021). [1] Earlier this year, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the NEA published the “14th Five-year Plan for a Modern Energy” system, which establishes the ambitious goal of developing a nuclear power capacity of 70 gigawatts (GW) by 2025, which would push China past France as the world’s leading producer of nuclear energy (NDRC, January 29). However, whether this elusive 70 GW target, first suggested in 2010 as a nuclear energy target for China to reach by 2020, is achievable by 2025 is doubtful. [2] As of this May, China has a total installed nuclear generation capacity of about 54.5 gigawatts, which estimates put at about 2.5 to 3 percent of its total energy production capacity (World Nuclear Association, updated July, 2022; China Electricity Council, June 17).

The lag between targeted and actual nuclear power generation testifies to the scale of China’s energy needs and the challenge to Beijing’s nuclear ambitions. It is also likely indicative that China is not immune to the delays and cost overruns that have bedeviled nuclear energy projects in the U.S. and elsewhere, due to a mix of safety-related issues and regulatory delays, and engineering and design inefficiencies (MIT, November 18, 2020). On nuclear power, China, along with a few select other powers- particularly France, is bucking the prevailing international consensus that nuclear is yesterday’s fuel, as renewable, and that solar and wind energy offer far cheaper, safer and more scalable alternatives. In late 2021, the financial advisory firm Lazard estimated that the levelized cost of energy, a measure of the average cost of energy produced by a generator over its life span, as ranging from $26 to $50 per megawatt hour (MWh) for wind power, between $28 and 41$ per MWh for utility scale solar power, and running from $131 to $204 for nuclear energy (Lazard, October 21, 2021). Nevertheless, it is important to note that in terms of nuclear energy, many of these costs are frontloaded and the levelized cost of electricity for a plant tends to trend down ove rtime (IEA, December 2020). China is clearly betting that the large-scale nuclear power stations it is building will provide a source of secure, reliable and carbon-free source of power generation for decades to come.

A Nuclear Option?

Unlike the U.S. and Russia, China is not blessed with abundant oil and gas resources, and hence, is largely dependent on imports. In 2021, imports comprised 72 percent of China’s crude oil usage (State Council Information Office, February 24). Nevertheless, China has several advantages that help alleviate its energy challenges. The first is its abundance of coal. The second is an abundance of rivers, which have allowed for extensive dam construction, making China by far the world’s largest producer of hydroelectric power. In terms of nuclear power, China also derives geographic benefits from its long coastline. As nuclear power stations require constant cooling, locating plants along coastlines is preferable as seawater can more effectively dilute and dissipate heat discharged in the cooling process (EMODnet, July 18, 2019). Nevertheless, as most of China’s major population centers are also located along its eastern seaboard, locating nuclear plants on the coast also increases potential safety concerns.

The 14th Five-year Plan (14th FYP) establishes China’s primary nuclear energy development effort as the “construction of three generations of nuclear power along the coastline” (Xinhuanet, May 13, 2021). Furthermore, the 14th FYP calls for developing offshore nuclear power platforms to further expand this coastal nuclear infrastructure. Notably, the 14th FYP also prioritizes development of advanced reactor technology, such as high-temperature gas-cooled reactors and small modular reactors (SMRs), which are more scalable, efficient and cheaper to operate than standard reactors, and are also considered generally safer because they produce less radiation. Last year, the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC, 中核集团, zhongkejituan) took a major step towards this goal, beginning construction on the world’s first onshore, commercial SMR in Hainan province (The Paper, July 13).

Officials and experts in China have long expressed enthusiasm over nuclear power’s potential to help China address its energy needs while also meeting its environmental goals. For example, Zhang Tingke, secretary general of China Nuclear Energy Association recently stated that in the first quarter of 2021, the PRC installed three new nuclear generation units increasing production by 3.4 gigawatts. Per Zhang, each gigawatt of nuclear energy “can effectively reduce carbon dioxide emissions by more than six million tons per year” (CGTN, June 25). Last month, state-run nuclear power provider- China National Nuclear Power Co, LTD (CNNP; 中国核电,zhongguohedian) released its first biodiversity conservation practice report, which touted the positive environmental impact of China’s nuclear industry (People.cn, June 22). According to the report, over the course of its history, China’s civilian nuclear energy program has had the equivalent ecological benefits as planting 3.6885 million hectares of trees.

The PRC’s massive buildup of its domestic nuclear power infrastructure is not without attendant safety concerns. Last summer, reports emerged that fuel rods at the Taishan Nuclear Power Plant in Guangdong province were damaged. As a result, the power station, which is operated through a joint venture between China General Nuclear Power Group (CGN) and the French nuclear conglomerate Electricite de France (EDF) was forced to shut down one of its reactors for maintenance (Nikkei Asia, July 31, 2021). Months after the shutdown, a whistleblower working in France’s nuclear power sector claimed that the situation at the Taishan plant was more severe than understood at the time with more than seventy fuel rods damaged, far more than CGN’s initial estimate that about five fuel rods had experienced minor damage (Radio French International, November 28, 2021).

King Coal Reigns On

As of 2020, coal comprised about 57 percent of China’s energy mix and nearly 70 percent of its CO2 emissions (CSIS China Power, Updated March 17). Moreover, China’s coal consumption (and hence emissions) continues to rise, even as global coal consumption has started to fall off (IEA). A central element of the energy and agricultural policies laid out in 14th FYP is seeking to increase domestic production to ensure energy and food security in an uncertain international environment (China Brief, June 17). Due to China’s enormous energy demand, the only way to make major short-term progress toward domestic self-sufficiency is to continue to rely on coal in the short-term, while waiting for new renewable and nuclear energy power projects to come on line over the long-term. In his remarks to a delegation from coal-rich Inner Mongolia during this year’s Two Sessions meetings, Xi reiterated a remark he is fond of making that “China’s natural condition is to be rich in coal, poor in oil and bereft of gas.” As a result, Xi said that “it is difficult to fundamentally alter the coal-dominated energy structure over the short term” and stressed that “we cannot abandon our means of living first, only to discover that our new livelihood has yet to arrive (People’s Daily, March 5).

In addition to increasing its domestic coal production, China has also sought to buy up coal at steep discounts that Russia is unable to sell elsewhere due to international sanctions. In April and May, Russia supplied almost 40 percent of China’s total coal imports (S&P Global, June 24, 2022).

Conclusion

A final factor that may drive Beijing to prioritize short-term, fossil-fuel reliant energy fixes is the continuing deterioration of U.S.-China relations. In its fury over U.S. Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan earlier this month, Beijing suspended eight U.S.-China dialogue mechanisms, including bilateral consultations on climate change (China Daily, August 6). The PRC took pains to stress that this move will not impact its commitment to multilateral climate change cooperation. For example, PRC Ambassador to the U.S. Qin Gang tweeted that although critics have asserted that “by suspending China-US climate talks, China is punishing the whole world”… “the US is not the whole world. China will stay committed to its climate goals, and actively participate in int’l [sic] cooperation on climate, as we have always done” (Twitter, August 8). Despite such protestations, China’s decision will likely damage multilateral cooperation on climate change, given the key role of the U.S. in both the international economy and global governance institutions. Moreover, spiraling geopolitical tensions with the U.S. will reinforce the PRC’s perception that it is operating in a more competitive security climate defined by the threat from an increasingly irreconcilable U.S. and its allies. In this context, the PRC is liable to prioritize its immediate energy security needs over slower-boil environment concerns, sustaining its push for energy self-sufficiency by boosting domestic coal production and primarily importing energy from close partner countries such as Russia and Iran. In the long run, however, Beijing appears to recognize that some combination of renewables, hydropower and nuclear energy offer the optimal path to a secure, sustainable and clean energy supply. The big question is how much coal China will need to burn to get there.

John S. Van Oudenaren is Editor-in-Chief of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, please reach out to him at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] For an English translation, see “Outline of the People’s Republic of China 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Range Objectives for 2035” [ 中华人民共和国国民经济和社会发展第十四个五年规划和2035年远景目标纲要], Georgetown University, Center for Security and Emerging Technology, https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/china-14th-five-year-plan/

[2] See MV Ramana, “Even China Cannot Rescue Nuclear Power from its Woes,” University of Colorado Boulder, April 12, 2022, https://www.colorado.edu/cas/2022/04/12/even-china-cannot-rescue-nuclear-power-its-woes