Moscow Worried About Ukrainian ‘Wedges’ in Russia and Their Growing Support From Abroad

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 115

By:

Executive Summary:

- Moscow has declared two movements in the ethnic Ukrainian regions of the Russian Federation as “extremist,” one in the Kuban and another in the Far East. The move reflects growing Russian concern about Ukrainian activism within Russia and outside support for it.

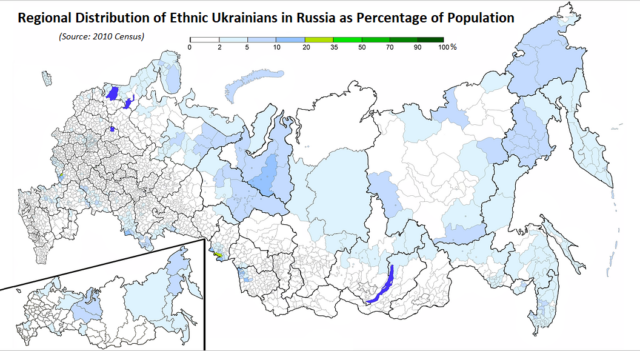

- These are only two of many historically Ukrainian regions within the Russian Federation, areas where, despite Moscow’s efforts, many people retain a Ukrainian identity and language even if compelled to officially list as or otherwise declare themselves Russians.

- Kyiv has given some rhetorical support to these areas, but activists from them say that Ukraine and others must do more to help ethnic Ukrainians within Russia. They argue and Moscow fears that these Ukrainians could become important allies against the Russian invasion.

Among the 55 groups the Russian Justice Ministry recently listed as “extremist,” two of the most important, if least well-known, are the ones committed to the independence of historically Ukrainian areas within Russia. These are the Kuban, between Ukraine and the North Caucasus, and what is usually called the Russian Far East (Russian Ministry of Justice, accessed July 30). Ukrainians refer to these areas and the many other historically Ukrainian regions within Russia by colors, with these two, the “crimson wedge” and the “green wedge,” respectively, being the largest (Window on Eurasia, June 12, 2014). Their respective movements champion the independence of these regions, the Crimson Wedge for an Independent Kuban and My Fatherland. Since 1991, and especially since Moscow seized Crimea in 2014 and began its expanded invasion of Ukraine in 2022, activists and officials in Ukraine have devoted more attention to these wedges and groups in hopes that they might cause problems for Moscow (Window on Eurasia, August 26, 2018; see EDM, January 18, 2023, January 25).

The largely rhetorical support, however, has not translated into more international attention, as these Ukrainian outposts have remained under the radar of most Western countries. Moscow has claimed success in convincing the residents of these areas to speak Russian and change their officially declared or at least recorded identities to Russian. These actions make it impossible to say precisely how large these Ukrainian groups are or how large a share of the local population they form. Even so, they still represent significant pluralities in these regions and majorities in some areas (Kmu.gov.ua, accessed July 30). Now, growing evidence highlights that Moscow’s efforts have not succeeded nearly as much as many think. The Kremlin is increasingly aware of this reality and that Moscow now feels compelled to go after those prepared to challenge its control of key portions of the Russian Federation.

Except for a few historians and demographers, the Ukrainian communities inside Russia have attracted relatively little attention in recent decades except when Moscow has focused on them as problems. The most important Russian attack came in January 2023, when Nikolai Patrushev, then-secretary of the Russian Security Council, expressed alarm about Ukrainian activism in the Far East. He suggested that many people there who declare themselves to be Russian are, in fact, Ukrainian at heart (see EDM, January 18, 2023). Now, as an assistant to Putin, Patrushev has returned to this issue by expressing concerns about Japan’s increasing willingness to project military power, a nation with a long history of involvement with the Ukrainians in the Far East (Fondsk.ru, July 28). (For background on Japanese-Ukrainian ties in the Far East, see Ivan Svit’s magisterial Ukrainian-Japanese Relations, in Ukrainian, 1972; John Stephan’s The Russian Far East, 1994; Project Syndicate, March 31, 2014; Regnum, June 9, 2018; Fondsk.ru, July 4, 2022; Window on Eurasia, August 8, 2023).

In March 2023, three historians presented an important exception to the neglect of these areas. This account makes attention to the Ukrainian wedges far more important than even skeptics about their future might believe. The historians demonstrated that during Stalin’s terror famine, death rates among ethnic Ukrainians inside the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic were higher than among neighboring ethnic Russians. This is compelling but rarely cited proof that the Holodomor was a genocide and not just the mass murder of peasants, as some still insist (Istories.media, March 10, 2023).

Due to the distance from both Moscow and Kyiv, Ukrainian activism in the Far East has been relatively small in scale. Scholars, nevertheless, have discovered that Ukrainian identity in the region, though admittedly in decline, has survived in important ways. Some Moscow commentators have even suggested that this ethnic background helps explain the restiveness in the region in general and in Khabarovsk protests in particular. This explains why the Kremlin has included a “green wedge” group in its latest list of outlawed “extremists” (Window on Eurasia, June 7, 2018, January 3, 2022; Sibreal.org, September 29, 2020). The survival of Ukrainian identities in the Kuban has been much greater. Activism by those seeking independence or unity with Ukraine is more prominent, and Russian attacks in response are both more frequent and on the rise (see EDM, January 24, 2023). (For detailed discussions on what has been going on, see the comments of the émigré leader of the Ukrainian wedge in Kuban at Apostrophe.ua, November 9, 2022; Kavkaz.Realii, June 6, July 26.)

Marina-Maya Govzman is perhaps the most instructive source concerning how things may develop in both Ukrainian wedge movements that Moscow has now declared extremist as well as a third, the “blue wedge.” This particular wedge is located in Omsk oblast just north of the Russian border with Kazakhstan. Other than when Moscow commentators have lashed out at its activists and sought to enlist Kazakhstan’s support in suppressing them, the “blue wedge” has almost never attracted much attention, even in Ukraine (Window on Eurasia, June 8, 2022). This is likely to change. Govzman, a journalist with the independent OVD-Info information portal, recently published one of the most comprehensive portraits of the blue wedge, where most people still speak Ukrainian and see themselves as part of Ukrainian culture. However, they have been divided by Russia’s war against Ukraine, with some going off to fight and others resisting despite police pressure (OVD-Info, June 20).

The residents in the “blue wedge” told Govzman that “in some villages, if you speak Russian, they immediately figure you are not from around here … In Blagodarivka [for example], children could not understand the young Russian-speaking teachers from the city, so retired teachers [who spoke Ukrainian] had to come back to work.” Others noted that local residents refer to their area as “Khokland,” a term that echoes Russian ethnic slurs against Ukrainians. The head of the local government acknowledges that “half the people here speak Ukrainian. Just go to the store and listen,” hardly the image of the dying Ukrainian identities Moscow has suggested—and many analysts accept. At the same time, Govzman continues, a significant number of people in the “blue wedge” nonetheless have accepted Kremlin propaganda and say, in Ukrainian, that Russia is fighting Nazis in Ukraine. Anti-war activists also make up a portion of the population. Some of them are animated by their Ukrainian memories and identities, which have been subject to official persecution (OVD-Info, June 20).

In the short term, this means that Moscow is likely to increase repression in the various Ukrainian wedges inside Russia’s current borders. Even so, such actions are unlikely to be the “end of history” for groups formed at the end of Tsarist times, when the Russian Empire encouraged Ukrainians to move to these areas. Instead, these groups are defined by their remarkable vitality despite many years of attempted Russification. Kyiv is paying increased attention to them, as is Japan. For a brief time in the mid-1980s, the United States recognized the importance of Ukrainians in the Far East, going so far as to try to broadcast programs aimed at the region’s residents in Ukrainian. All in all, the wedges are likely to become more important in Russian and Ukrainian history than ever before (Stephan, The Russian Far East).