BRIEFS

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 21

By:

BANGLADESH ATTACKS SHOW INCREASING ISLAMIC STATE INFLUENCE

James Brandon

In the last six weeks, Bangladesh has been hit by a near-unprecedented series of Islamist militant attacks targeting foreigners and local Shi’a Muslims. On September 28, an Italian NGO worker, who was residing in the country, was shot and killed by attackers on a moped as he was jogging near the diplomatic area of capital city Dhaka (Daily Star [Dhaka], September 29). A few days later, on October 3, a Japanese aid worker was killed by gunmen in Rangpur, following which the Islamic State group reportedly claimed responsibility for the attack online (BDNews24, October 4). Soon afterwards, on October 5, a Christian Baptist priest was badly injured after being slashed by men in the town of Iswardi; five members of the Jama’at ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) militant group were subsequently arrested for their suspected involvement (BanglaNews24, October 13). The attacks follow a string of mostly fatal knife and machete attacks on secular and atheist Bangladeshi bloggers earlier in the year, and underline how militant attacks in the country have recently trended towards being extremely low-tech. Attacks have also targeted specific individuals variously accused of insulting or challenging Islam, the country’s dominant religion.

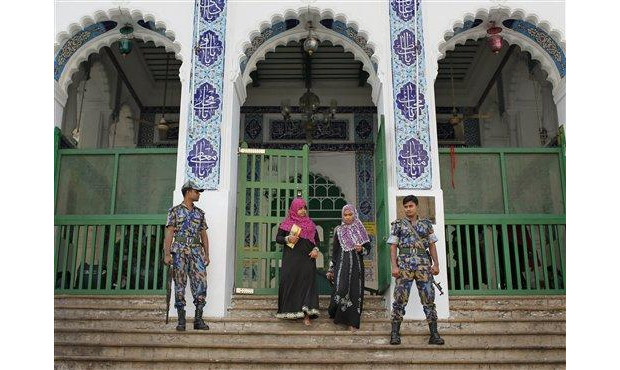

In a departure from this trend, however, on October 24, bomb attacks targeted the Hossaini Dalan Imambara, the most significant Shi’a shrine in Dhaka. One 14-year-old boy was killed, and others were injured. The attack occurred shortly before a pilgrimage to mark the Ashura festival, the most important in the Shi’a calendar, was due to take place. According to local investigators, the attacks involved three homemade bombs being detonated in one section of the facility, following which two more bombs were thrown into the crowd as people sought to flee the first explosions (Dhaka Tribune, October 27). The attack is reported to be the first such sectarian attack on the Shi’a shrine since its construction in the 17th century, underlining the impact of the influx of Wahhabi-derived ideologies on the country’s complex religious make-up.

The Islamic State group, whose Wahhabi-influenced ideology is heavily focused around denouncing Shi’as as non-Muslims, subsequently claimed credit for the attack on the shrine via some of their commonly used Twitter profiles (Daily Star [Dhaka], October 24). Bangladesh’s Home Minister, however, cast doubt on the group’s claims of involvement, both in the shrine attack and in the prior assassinations: “Those who claim to be Islamic State here are offshoots of militant outfits Huji, al-Qaeda and JMB [Jama’at ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh]. They all have their roots within Jamaat-Shibir” (Daily Star [Dhaka], October 25). Still, while it may be true that these attackers often derive from existing domestic Bangladeshi militant groups, this does not meant that these individuals are not now affiliated with the Islamic State’s global movement. Indeed, the fact that the attackers may have had such links to extant local militant groups strengthens recent observations that the Islamic State is succeeding in becoming an effective umbrella group for many smaller jihadist groups worldwide, including in South Asia, as well as a significant ideological lodestar for jihadists globally.

Confusing the issue further, the Bangladeshi government has also sought to use the recent series of attacks to score points against their political rivals, most notably in a series of bizarre statements about the fatal attack on the Italian NGO worker in Dhaka and the Japanese aid worker in Rangpur. For instance, on October 28, the Joint General Secretary of the country’s ruling Awami League Party said that the orders for the targeted killing of the two foreigners “came from London,” an apparent reference to leadership of the its archrival, opposition Bangladesh National Party, some of whom are based in London (Daily Star [Dhaka], October 28). More troubling, this highly unlikely accusation was also repeated by the investigating police authorities, who said that the “big brother” said to have funded that attacks had wanted “to take advantage by creating unrest in the country” (Dhaka Tribune, October 27). The statements underline the challenges that Bangladesh faces, firstly in correctly identifying the recent attacks as being rooted in an emerging link-up between local jihadist groups and the Islamic State, and secondly in tacking effective action against this emerging—and clearly potent—nexus.

RECENT GAINS AGAINST THE ISLAMIC STATE IN IRAQ POINT TO GROWING COALITION CAPABILITY

James Brandon

Iraqi government forces, and their Iran-backed Shi’a allies, scored a significant victory in mid-October when, after a seven-month battle, they succeeded in recapturing Baiji, a strategic town and oil refinery on the main highway connecting the capital Baghdad with Islamic State-held Mosul, the country’s third-largest city. The recapture of Baiji is a small but significant development in the Iraqi government’s struggle against the jihadist organization, and is further evidence of government forces’ slow progress north, through mainly Sunni areas, toward Mosul as well as of the Iraqi military’s slowly increasing competence and abilities. Following its capture, Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi visited the town and lauded the its recapture from the Islamic State, which he said “brought out the capacity of Iraqis and their persistence until they liberated their city,” while he also praised the “martyrs” who had fallen in the fight (Rudaw, October 24; Prime Ministers’ Office, October 23).

Striking a different note, however, Iranian media linked to that country’s government and religious establishment, drew particular attention to the role of Iran-backed Shi’a militias in the battle, singling out for particular praise the Imam Ali Battalion, effectively the armed wing of Harakat al-Iraq al-Islamiyah (Movement of the Islamic Iraq), many of whose leaders are linked to the strongly anti-U.S. Sadr movement (Tasnim News, October 20). By contrast, various Sunni Islamist groups, both inside Iraq and globally, responded to the recapture of Baiji by launching their own counter-propaganda aimed at the Iraqi government and their Shi’a allies. For instance, the influential UK-based British Muslim Brotherhood-linked website Middle East Monitor, ran an alarmist article quoting Shaykh Abdul Razzaq al-Shammari, an Iraqi Sunni tribal Islamist leader, as accusing Shi’a-backed militias in Baiji of burning eight—presumably Sunni—mosques in the area and of committing a “genocide” (Middle East Monitor, October 26). These divided and starkly polarized responses to the Iraqi government’s advances against the Islamic State highlight the risk that the ongoing conflict in Iraq, and particularly the upcoming battle for Mosul, will be used by hardliners on both sides to further stir up sectarian tensions across the region.

Meanwhile, the news of a joint U.S.-Kurdish raid on an Islamic State prison in Hawija, also in Islamic State-held Sunni areas of northern Iraq, drew attention to the ongoing role of special forces units in the conflict. The nighttime attack, launched by helicopter on the night of October 22, freed 70 prisoners, killed at least 15 Islamic State members and captured others; however, one experienced U.S. special forces soldier also died in the attack (Rudaw, October 22). Although the raid was unusually large in scale—and its publicization, including the release of helmet-camera footage of the raid, was also relatively novel—the action nonetheless drew attention to both the Kurds’ increasingly effective special forces, and also the close relationship between them and their U.S. mentors. Such units can be expected to play an increasing role against the Islamic State in coming months, both in supporting ground offensives and in conducting further behind-the-lines operations, which may well begin to directly target the jihadist leadership with the aim of seriously damaging the group’s military capacity and credibility.

Meanwhile, more conventionally, the U.S. military continues to conduct almost daily airstrikes against Islamic State forces in Iraq, providing both strategic and tactical-level support to Iraq forces on the ground. For instance, on October 27, Combined Joint Task Force–Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) said that its “bomber, fighter and attack aircraft” had conducted a total of 14 strikes on the day against Islamic State targets. Some of these near Mosul, likely in close support of Kurdish forces, “struck two separate tactical units and destroyed two fighting positions and an heavy machine gun” (CENTCOM, October 28). Similar attacks in Sinjar, where Kurdish forces are preparing an offensive against the militant organization, struck Islamic State “tactical units,” “fighting positions” and a “mortar position.” By contrast, other strikes on the day away from the front-lines targeted Islamic State rear-area facilities. For instance in Tal Afar, these hit a “weapons storage area, an [Islamic State] logistical facility, and an staging area.” The day’s activities give a reasonable representation of the U.S. military’s daily aerial operations, which for now at least are focused on gradually degrading the organization’s capabilities and morale, while also supporting localized engagements against the Islamic State by friendly forces, and particularly the Kurds. Taken together, these developments—the Iraqi military and Shi’a militias’ growing ability to dislodge strongly held Islamic State positions in Sunni areas, the Kurds’ growing special forces capability and the U.S. military’s pin-point intelligence-driven airstrikes—point to the likely modus operandi to be followed by the coalition forces in the coming months as the critical battle for Mosul draws inexorably near.