A Shiite Storm Looms on the Horizon: Sadr and SIIC Relations

A Shiite Storm Looms on the Horizon: Sadr and SIIC Relations

Post-Baathist Iraqi politics is undergoing a dramatic change, and the Sadrists and the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council (SIIC), formerly known as the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), are leading the way by bringing a major shift in the balance of power. With the gradual decomposition of Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki’s National Unity Government, mainly dominated by Shiite and Kurdish parties, Iraq is entering a new political era. As splintered political factions, such as the Sadrists, seek to form a new coalition made up of Sunni parties, formerly exiled Shiite groups like Da’wa and the SIIC are facing new challenges in maintaining a dominant political bloc in Baghdad.

Moqtada al-Sadr’s call to create a “reform and reconciliation project,” which would also include Sunnis, is a radical departure from his sectarian base which was formed with the United Iraqi Alliance (UIA) and under the spiritual leadership of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani in 2004 (al-Hayat, May 8). In addition, al-Sadr’s move is a direct challenge to his main Shiite rival, the SIIC, which has posed the most serious threat to al-Sadr’s political prestige and leadership in Iraq since 2003. For the most part, limited political mobility in the UIA and the al-Maliki government itself were the sources of frustration for the Sadrists, and most of the blame was directed at the SIIC for its political tactics to tame the Sadrist movement in the government.

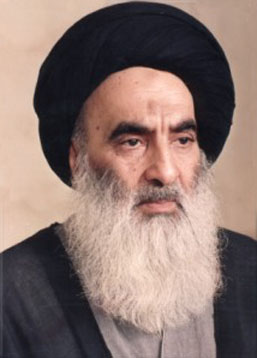

SIIC leader Abdul Aziz al-Hakim’s May 13 call to change the name of the party from the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq to the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council, dropping the word “revolution” from the name, also brings to light a key move by Iraq’s leading Shiite politician in preparing for the post-coalition era (al-Hayat, May 13). As the leader of Iraq’s largest party, backed by possibly the largest militia in the Middle East, al-Hakim’s new strategy also includes a renewed pledge of allegiance to Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani and his Najaf-based religious organization (al-Jazeera, May 13; Terrorism Monitor, November 7, 2003). The reason for this symbolic reaffirmation of the party’s political position is clear. Al-Hakim aims to distance his party from its exiled past when the party was based in Iran from the early 1980s to 2003, and reconstruct a Shiite Iraqi identity by aligning with the Najaf clerical authority. The call was also an attempt to establish distance from the Iranian shrine city of Qom, where Ayatollah Khamenei has considerable power over the religious and political institutions (https://historiae.org, May 12).

Both factions are taking new positions in a shifting political landscape. Due to the failure of the constitutional drafting process, tensions over key political issues, such as federalism and the distribution of oil, are paving the way toward a major Shiite-on-Shiite conflict. The two parties appear to expect some sort of a political confrontation over the constitution after the future collapse of the al-Maliki government. What these new strategies also indicate is how the weakening of the Iraqi government is forcing Sadrists to expand their military prowess for control over cities and regions that are at the moment dominated by the SIIC’s militia group, the Badr Organization. A major clash between the two Shiite parties can be expected in the future, and only a viable political solution can prevent a full outbreak of conflict.

Arch Rivals

The early history of Sadrist-SIIC conflict dates back to the competition between the al-Hakim and al-Sadr clan families over influence in the Da’wa party since its inception in 1959. When Ayatollah Baqir al-Sadr, the uncle of Moqtada, emerged as the most prominent leader of the Da’wa movement, Ayatollah Muhammad Baqir al-Hakim, as an active member of the party, was eclipsed by al-Sadr. Energetic, contemplative and charismatic, Baqir al-Sadr’s impact as a political leader was so deep that after his assassination in 1980 he continued to aspire a cult-like following among the Shiite Iraqis. However, a major split in Shiite politics occurred when al-Hakim formed SCIRI (al-Majlis al-A’la lil Thawra al-Islamiya fil Iraq) in Tehran on November 17, 1982, with the help of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The formation of SCIRI in Iran was perceived by many Shiite Iraqis, including Moqtada al-Sadr’s father, Ayatollah Sadeq al-Sadr, who later formed the Sadrist movement in the 1990s, as an Iranian intervention in the native Shiite Islamic politics, which was believed to remain a homegrown movement. Since its inception, SCIRI has been perceived as an alien, foreign agent by most Sadrists.

With the failure of the Badr Brigade’s (Faylaq Badr) military venture against Saddam’s army during the Shiite uprising in 1991, SCIRI’s chance to win the popular support of the Shiite population was reduced considerably. The death of Ayatollah Khoi, the country’s most senior cleric, in 1992 opened the way for the formation of alternative native Shiite movements to energize Shiite aspirations for freedom from Saddam’s tyrannical rule, and Ayatollah Sadeq al-Sadr emerged as a leading candidate.

Sadeq al-Sadr’s power base was so deeply grounded in the plebian Shiite population, especially in eastern Baghdad, that still four years after his assassination by Saddam’s regime his movement continued to expand. On entering Iraq after more than 20 years of exile in Iran in 2003, al-Hakim witnessed the rise of a major Shiite political rival, a young cleric named Moqtada al-Sadr, who would publicly question his bravery and Iraqi credentials for not only failing to stand up to Saddam, but also for being a foreign agent backed by the Iranian government.

Violence has frequently erupted between the Mahdi Army and the Badr Organization since 2004 in cities like Baghdad, Basra and Diwaniya, and all of these clashes have their roots in this complicated historical setting. Yet such tension also reflects how each of these two parties aim to control the future of the country. Domination of the oil production in Basra and military control of major southern Iraqi provinces, especially in eastern Baghdad, is the key problem to this growing dilemma. There is also a major ideological rift: the envisaged future of Iraq as a nation-state by the two parties.

Although Sadrists are staunchly Shiites, they are, however, fervidly opposed to al-Hakim’s August 2005 call for the formation of a nine-province Shiite region, with Basra as the major governmental center. As Iraqi nationalists, Sadrists are highly suspicious of a federalist model for Iraq and consider al-Hakim’s proposal as one that would snatch away economic and political power from supporters of al-Sadr based in Baghdad. Al-Hakim, on the other hand, opposes al-Sadr’s call for an alliance with Sunni Arabs and since 2004 has been hesitant to accept a deadline for a U.S. troop withdrawal from Iraq (Baztab, February 2004). Al-Hakim is worried that once U.S. forces leave Iraq, the Badr militia would have to confront the Mahdi Army and al-Sadr’s young followers in Baghdad and Basra. Distrust of the adversary remains a major problem.

Iran and the al-Sistani Factors

In the middle of this conflict lies Iran and al-Sistani. By and large, both have a significant stake in this subtle standoff between two of Iraq’s major political factions. Since an outbreak of conflict between the rival groups could harm their authority and influence in Iraq, Najaf and Tehran are doing their best to prevent a clash. Iran is desperately attempting to muster enough Shiite support for both expanding its influence in Iraq and protecting itself from potential U.S. attacks against its interests in the region. Al-Sadr could be a huge asset for Iran’s regional ambitions, but he could also be a liability. For Tehran, al-Sadr is an independent Shiite voice who needs to be tamed and brought into the Qom-based Shiite power base with Khamenei recognized as the main source of authority.

Al-Sistani, however, shares al-Sadr’s vision of a united, non-sectarian nation-state, but he vehemently opposes his youthful aspiration for power in Iraq. For al-Sistani, al-Sadr should be tamed and brought into the Najaf-based Shiite power base with al-Sistani and the other leading Shiite clerics recognized as the main sources of authority. SIIC’s recent pledge of allegiance to al-Sistani, then, could be viewed as a shrewd way to create a rift between Najaf and al-Sadr by forcing al-Sistani to choose sides between them—even though al-Sistani would most likely refuse such factional politics. Despite al-Sadr’s growing relationship with al-Sistani since the summer of 2006, al-Hakim knows that al-Sistani views al-Sadr as a potential threat to the Najaf orthodoxy (Terrorism Monitor, March 29). Therefore, SIIC’s tactic is to indirectly force al-Sadr to become estranged from Najaf by renewing the party’s allegiance to al-Sistani; at this crucial stage of the political game, it appears that alienating al-Sadr from Najaf remains a high priority for al-Hakim.

Yet, al-Hakim’s political strategy is two-fold. By getting closer to al-Sistani, SIIC is building alliances with both Najaf and Tehran. Yet, he also appears to be expanding Khamenei’s influence in Najaf, where the Badr Organization is controlling the shrine city, a symbol of Shiite power. Regardless of Tehran’s involvement in al-Hakim’s recent change of tactics, SIIC realizes that al-Sadr is a major threat to the party’s influence, and that with the rapid rise of his popularity since 2006, both al-Sistani and Iran could play a major role in backing al-Hakim’s party in case of a major eruption of conflict.

Policy Implications

The potential descent into an intra-sectarian civil war poses a serious danger to Iraq and the region. This sort of civil war could contribute to the formation of new Shiite groups, destabilization of the Iraqi government and the southern provinces, especially Basra, and lead to serious humanitarian catastrophes. Although such intra-sectarian conflict is essentially a political one, it also includes a significant religious component. Iraq is undergoing a shift in the balance of power among Shiite militant groups, and the best Washington can do is to hope for the victory of the orthodox Shiite institution in Najaf. It is with the authority of al-Sistani that fighting between these two militia groups can best be prevented.

The most practical strategy that the United States could adopt at this stage is to prevent the meltdown of the Iraqi government into a state of political factionalism; in reality, Iraq’s worst enemy at this moment is the Baghdad government itself. The reason is that with the absence of a relatively centralized state, militias (regardless of their ethnic and sectarian associations) are bound to expand and continue to fight among themselves (and Iraqi and U.S. troops) for power. This general strategy also means that Washington should recognize the pivotal role of political integration, rather than military operative tactics (like the troop surge), against the radicalization of Shiite groups.

Regardless of the success or failure of the surge, the post-coalition era would need to see the formation of inter-sectarian political parties. In light of his recent call for the creation of a “reform and reconciliation project,” al-Sadr could possibly lead the country to a new post-Baathist political era, in which Shiite and Sunni nationalists, who remained in Iraq during Saddam’s reign, could unite against former exiled Shiite and Kurdish parties like the SIIC and the Kurdistan Democratic Party. The United States should encourage such political coalitions, despite its obvious anti-occupation (or anti-American) fervor. Nevertheless, although this new coalition can lessen sectarian tensions, it will not, however, do away with the Shiite militia competition over power and prestige. An SIIC-Sadrist clash looms ahead, and the best Washington can do is to contain it through an already fragile Iraqi government.