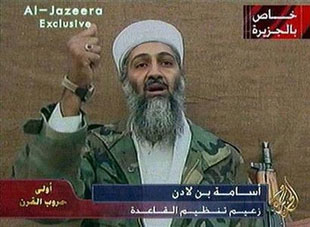

Assessing the Six Year Hunt for Osama bin Laden

Publication: Terrorism Focus Volume: 4 Issue: 30

More than six years after the September 11 attacks, Osama bin Laden remains free, healthy and safe enough to produce audio- and videotapes that dominate the international media at the times of his choosing (Terrorism Focus, September 11). Popular and some official attitudes in the United States and its NATO allies tend to denigrate the efforts made by their military and intelligence services to capture the al-Qaeda chief. The common question always is, “Why can’t the U.S. superpower and its allies find one 6’5″ Saudi with an extraordinarily well-known face?” The answers are several, each is compelling, and together they suggest that the U.S.-led coalition’s military and intelligence forces are too over-tasked and spread far too thin to have more than a slim chance of capturing or killing bin Laden and his senior lieutenants.

The first factor is the issue of topography. Few U.S. citizens or Europeans have any idea of what the terrain of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border looks like (Terrorism Monitor, October 19, 2006). This shortcoming must be attributed to the failure of Western leaders to educate their electorates using the abundant and commercially available satellite photography that depicts the nightmarish mountains, forests and road-less terrain in which Western forces conduct their search. The border area is genuinely a frontier in the sense of the American Old West, but with mountains that dwarf even the Rockies. Such use of satellite photography would likewise show voters that the Western concept of a “border” as a well-defined and manageable demarcation between two nation-states is not remotely applicable regarding the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

The second factor is the role of the indigenous population. Bin Laden and his lieutenants appear to currently reside in a region dominated on both sides of the border by the Pashtun tribes. Ethnically and linguistically, the Pashtun are fairly homogenous, but the multiple tribes are divided and subdivided into myriad, often rival clans. What all Pashtuns share, however, is a quite conservative brand of Islam and a tribal tradition that insists that no individual, once accepted as a guest by the tribe, ever be surrendered to those seeking him and that he be defended to the death. Buttressing this tribal stricture in bin Laden’s case is the fact that the Pashtuns are conservative Muslims, and regard him—as does much of the Muslim world—as an Islamic hero. The strength of this combination is evident when it is noted that no Pashtun has stepped forward to collect a cent of the tens of the millions of dollars the United States is willing to pay for information leading to bin Laden’s capture or death.

It also is worth noting that the Pashtun custom of guest protection and their tendency to evaluate bin Laden as an Islamic hero is more or less shared by all Sunni Afghans, that it is a near-countrywide Afghan characteristic. Thus, the U.S.-led coalition’s military and intelligence personnel are likely to encounter these attributes along most of the 1700-kilometer Pakistan-Afghanistan border in areas north and south of the Pashtun-dominated central border area. In addition, the Afghans’ traditional hostility to foreign occupation traverses all ethnic groups and this nearly universal attitude is likely to be encountered with increasing stridency as the coalition’s presence progresses through its seventh year. Recent media reporting, for example, shows that some mujahideen groups in the pro-Karzai Northern Alliance’s heartland are beginning to reform on the basis of a desire to rid Afghanistan of what they view as its current set of foreign occupiers.

The third factor is the coalition’s choice of major search areas. In many ways, the hunt for bin Laden depends on clandestinely acquired information, and those who comment on the effort—including the present author—must admit that they are commenting and analyzing on the basis of informed speculation, common sense and historical precedent. For the past several years, the hunt for bin Laden has been concentrated in Pakistan’s Waziristan region and the area adjacent to it on the Afghan side of the border (Dawn, February 20). Coalition and Afghan forces, Pakistan’s intelligence service and border guards, and the Pakistani regular army have been involved in the hunt. One must assume that credible information has led them to that location. Nevertheless, there are several good reasons that make Waziristan an unlikely top choice as a hiding spot for bin Laden and his lieutenants.

A. Although clearly a remote area, Waziristan is an area through which much commerce and smuggling take place. In addition, there is a great deal of simply tribe-, clan-, or family-related movement through the area because of the trans-border ethnic homogeneity (Terrorism Monitor, October 19, 2006). Of the entire length of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, only the Kandahar-Chaman-Quetta and Kabul-Jalalabad-Peshawar corridors have more of such activity, making Waziristan an area in which everyday human and business traffic provides substantial cover for those hunting a fugitive, and thereby making it a relatively unattractive refuge.

B. Waziristan was a major staging and training area for the Afghan mujahideen and their non-Afghan allies during the anti-Soviet jihad of the 1980s. As a result, the Pakistani, American and Russian governments hold a good deal of information about the location of camps, depots and hideouts built by the Afghan mujahideen. This kind of information also is held by some of the war correspondents who covered the Afghan-USSR war, and who are now covering the present insurgency. It seems fair to conclude that the anti-Soviet mujahideen built their facilities in what they determined were the most secure locations in Waziristan, and that bin Laden and his lieutenants are fully aware that their current enemies have knowledge of these bases, and so they would not seek safe haven in places known to those hunting them.

C. The U.S. government, its NATO allies, President Hamid Karzai’s administration and scores of Western media reporters and terrorism “experts” have, over the past six years, made no secret of their belief that bin Laden and his leadership team is in Waziristan. The U.S.-led coalition’s military, diplomatic and political officials repeatedly have said publicly that they are putting much of their resources into the Waziristan-focused hunt of bin Laden and his organization. As a result, bin Laden would have to be unintelligent to stay in Waziristan in the face of his enemies’ providing him with credible and detailed intelligence about their focus and intentions.

While based on the region’s history and informed speculation, the northeastern Afghan areas of Konar province and Nuristan and the adjacent Bajaur Agency in Pakistan lend themselves far better to bin Laden’s security needs:

A. This mountainous region is one of the most remote and rugged in Afghanistan; it is the virtually inaccessible area in which Rudyard Kipling set the events of his timeless story, The Man Who Would Be King. Roads are few, the population is scattered and it hosts nothing like the commercial and smuggling activity found in Waziristan (Terrorism Monitor, October 19, 2006). Additionally, in terms of the quality of maps available to bin Laden hunters, this region is much less well-documented than the admittedly poorly mapped Waziristan area. The topography, therefore, favors anyone trying to hide because, once positioned on the high ground, fugitives will have an early visual warning of any approaching foe. The terrain likewise favors the hit-and-run and ambush tactics of insurgent fighters. During the anti-Soviet jihad, for example, the Communist garrison stationed in Konar’s capital of Asadabad was more or less marooned. Operations staged from the city were never a surprise, and were often met by ambushes. Likewise, convoys bringing reinforcements and supplies from the south were often ambushed.

B. The areas of Konar and Nuristan also were strong mujahideen redoubts during the Afghan-Soviet war. Indeed, the first resistance to the Soviet-backed regime in Kabul originated in Nuristan in 1978, and the region itself hosted forces belonging to several prominent mujahideen commanders. The most important of these, from bin Laden’s current perspective, is Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and his Hezb-e-Islami organization (Terrorism Monitor, September 21, 2006). An early sponsor and longtime friend of bin Laden—he helped facilitate the al-Qaeda chief’s return to Afghanistan in May 1996—Hekmatyar maintains strong forces in parts of Konar province and most of adjacent Laghman province to the east. Media reporting likewise indicates that another al-Qaeda ally, the Kashmiri Lashkar-i-Taiba maintains a presence and perhaps training facilities in Konar province. In terms of jihadi colleagues, the region appears well-stocked with bin Laden’s allies.

C. The Konar-Nuristan-Bajaur Agency area also has been a region on which Salafi missionaries from Saudi Arabia and other Arabian peninsula states have focused their proselytizing efforts for several decades. Saudi fighters were allowed by the population to train in the region during the war against the USSR, and today it stands as one of the most—and perhaps the most—Salafi area in South Asia. As a Salafi himself, bin Laden would be sure to find the area both welcoming and religiously comfortable. This shared Salafism, moreover, would add another measure of security for bin Laden as his co-religionists are unlikely to cooperate with those seeking his apprehension.

D. This region also is one that bin Laden had his eye on as home since his 1996 return to Afghanistan. When in the spring of 1997 he was preparing to leave his residence in Nangarhar province after several assassination attempts on his life, bin Laden’s inclination was to proceed north into the Konar-Nuristan area. He decided against this plan, however, when the Taliban invited him to live in its capital at Kandahar. He then believed it would be politically unwise for al-Qaeda to turn down an invitation from Afghanistan’s de facto government. No such consideration is now relevant.

The fourth and final factor is the lack of resources devoted to the hunt. Given Afghanistan’s sheer size and extraordinarily mountainous terrain, the current level of forces available to the U.S.-led coalition appears inadequate to perform all the tasks it has been assigned. In addition to eliminating bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri and al-Qaeda, for example, the coalition’s forces are being asked to keep President Karzai’s government in power, rebuild the country’s economy and transportation infrastructure, help organize a democratic political system, defeat the growing Taliban-led insurgency and eliminate the world’s largest heroin industry. Of the 50,000 total coalition troops at their command, it seems unlikely that U.S. and NATO commanders can field more than half of that total as combat forces; indeed, some NATO contingents are forbidden by their governments from performing combat duties. That force seems inadequate for the tasks assigned to it, and may well be outnumbered by the manpower involved in the growing Islamist insurgency.