Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan Seek to Expand Cooperation on Caspian Energy Production

Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan Seek to Expand Cooperation on Caspian Energy Production

A 30-year feud over an offshore oil field located between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan in the Caspian Sea has finally come to an end. In mid-January 2021, Ashgabat and Baku agreed to the joint development of the large field, now renamed Dostlug, which means “Friendship” in both languages (Azadliq.org, January 21, 2021).

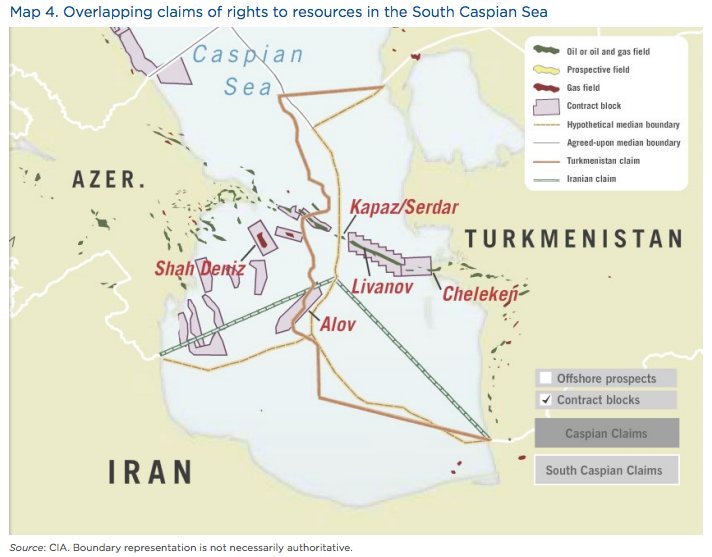

The name itself and the pomp that accompanied the announcement of the signed Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) highlighted the ongoing thaw in relations between the two Caspian littoral states. For now, there has been no information available about the details of the joint development deal: no data on profit splits or other arrangements, including logistics. Nevertheless, news of the bilateral accord raised hopes in some quarters that the long-awaited Trans-Caspian natural gas pipeline (TCP), which could feed into the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), might finally also be realized. The SGC, spearheaded by Azerbaijan, delivered its first Caspian-basin gas from the offshore Shah Deniz field to Greece and Bulgaria on December 31, 2020 (see EDM, January 19, 2021).

The recently signed MoU is not the only positive step in relations between two countries over the past two months. In December, Azerbaijan’s SOCAR Trading (a subsidiary of the state-owned oil and gas giant SOCAR) won the bid to procure 30,000–40,000 tons of petroleum per month produced by Eni Turkmenistan from Turkmenistan’s Okarem field. Experts believe these volumes of Turkmenistani oil will be routed via the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline, and away from transit through Russia’s Makhachkala and Novorossiysk ports (Report.az, December 14, 2020).

Originally called Kepez or Serdar by Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, respectively, the now-rechristened Dostlug oil field was the primary irritant in bilateral relations since the two countries’ independence from the Soviet Union. The field, which holds an estimated 50 million tons of reserves, was offered by both governments to interested hydrocarbon extraction companies in the mid-1990s, but to no avail (Neftegaz.ru, June 2, 2012). For a time, Russia’s Rosneft and Lukoil tried to work with Azerbaijan to develop the field, while the United States’ Mobile (now Exxon) signed a preliminary agreement with Turkmenistan. Both deals ultimately fell apart, however, as Baku and Ashgabat failed to find middle ground on sharing the undersea reserves. Turkmenistan also previously vied with Azerbaijan over claims to the offshore Azeri and Chirag fields. But it later dropped its grievances given the successful development of those fields by a Baku-approved consortium led by BP. That assent by Ashgabat in Baku’s favor did not apply to Serdar/Kepez (see EDM, April 5, 2018).

The source of the Serdar/Kepez dispute was the two sides’ different interpretations of the law on the Caspian Sea demarcation. The field, which lies 184 kilometers off Azerbaijan’s coast and 104 kilometers west of Turkmenistan’s shoreline, was discovered by Azerbaijani specialists when both countries were still constituent republics of the Soviet Union. This fact and the drilling of the first exploratory well by Azerbaijan served as Baku’s main legitimization of its claim. Turkmenistan refuted these arguments, however, insisting instead on the oil field’s relative proximity to its coast.

The settlement, in 2018, of the row over the Caspian Sea’s legal status among the five littoral states, including Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, went a long way toward facilitating the resolution of the Serdar/Kepez dispute (BBC News—Azerbaijani service, August 13, 2018). However, demarcation was likely not the only factor that contributed to the process—and the associated wider thaw in bilateral relations.

One of the reasons may arguably have been Ashgabat’s desire to diversify its export options for both oil and natural gas. Turkmenistan is a significant gas exporter and holds much greater proven reserves of this energy source than Azerbaijan. However, unlike Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan lacks diversified export outlets. Turkmenistan’s primary buyer is China, to whom the Central Asian state exported 30 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas, via the Central Asia–China pipeline, in 2019 (Orient.tm, July 7, 2020). But plummeting global demand for gas due to the COVID-19 pandemic, along with competition over the booked capacity in the pipeline even prior to the coronavirus crisis, made it difficult for Ashgabat to guarantee a secure export outlet and maximize the monetization of its vast gas volumes (Radio Free Asia, August 2017). Oil prices plummeted to $15 per barrel in March 2020 due to the pandemic, while global gas prices followed the trend. In Europe, for instance, natural gas prices collapsed from more than $200 to between $40 and $50 per million British Thermal Units (MBTU) (Finanz.ru, April 22, 2020). Furthermore, Turkmenistan’s plans to lead the construction of the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India (TAPI) gas pipeline also failed to come to fruition, while Beijing is not rushing with the construction of the promised fourth line of the Central Asia–China pipeline (Natural Gas World, January 21, 2021).

Relations with Russia, once the primary importer of Turkmenistani gas, rebounded in 2019, and Ashgabat has again started exporting some of its gas via the Russian route. Yet for now, these volumes (around 6 bcm per year) are much lower than what Moscow was buying annually from Turkmenistan before 2015 (10–11 bcm), while the price Ashgabat can charge is also substantially lower (SPGlobal, April 16, 2019). Turkmenistan is being careful not to repeat the same mistakes from earlier decades that made it dependent on Russia as a transit/importer country. Seeing the SGC, a network of pipelines stretching from the Caspian Sea all the way to Italy, complete and actually operating may, therefore, encourage Ashgabat to take more proactive steps over the coming months or years to join the project.

Now that one of the most significant irritants in relations with Turkmenistan has been eliminated, Azerbaijan may try to refocus on implementing the long-planned Trans-Caspian Pipeline, which would bring much-needed transit revenues for Baku while, at the same time, contributing to the further diversification of Europe’s gas import portfolio. The project, however, still faces formidable challenges. One of them is the TCP’s commerciality, given plummeting energy commodity prices in 2020 and chronic fluctuations in the gas price due to oversupply. One should also not discount the Russia factor: Gazprom would be legitimately concerned to see the SCP supplying Southeastern Europe with more than the current 10 bcm of gas per year, something that both Ashgabat and Baku will have to be wary of. Baku already has experience in politically maneuvering around the Kremlin’s latent objections to its transnational pipeline projects (BTC, SGC). Ashgabat will need to show the same political resilience if it hopes to genuinely diversify its export alternatives.