Beijing Asserts a More Aggressive Posture in Its Border Dispute with India

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 12

By:

Introduction

On the night of June 15, a violent clash occurred in the Galwan Valley between soldiers of the Indian Army and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which resulted in the death of 20 Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of Chinese troops (India Today, June 17; Jamestown Foundation, June 29). In a first sign of efforts to de-escalate tensions along the Line of Actual Control (LAC)—the de facto border between Indian and Chinese-controlled territories—India and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have begun pulling back their troops from recent sites of confrontation in Ladakh.

According to Indian media reports, the step-by-step disengagement process began on July 6, following a two-hour telephone conversation between India’s national security adviser Ajit Doval and PRC State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅). Citing unnamed sources in the Indian Army and security establishment, the reports say that Indian and Chinese troops have moved back 1.8 kilometers from the Galwan Valley’s Patrolling Point (PP) 14—the site of the June 15 clash—and that the PLA has dismantled a military camp and tents it had erected here (Indian Express, July 7). Both sides are said to have pulled back from Gogra-Hot Springs as well, although no such action has been taken at Pangong Tso, a lake that straddles the LAC in Ladakh (Indian Express, July 7).

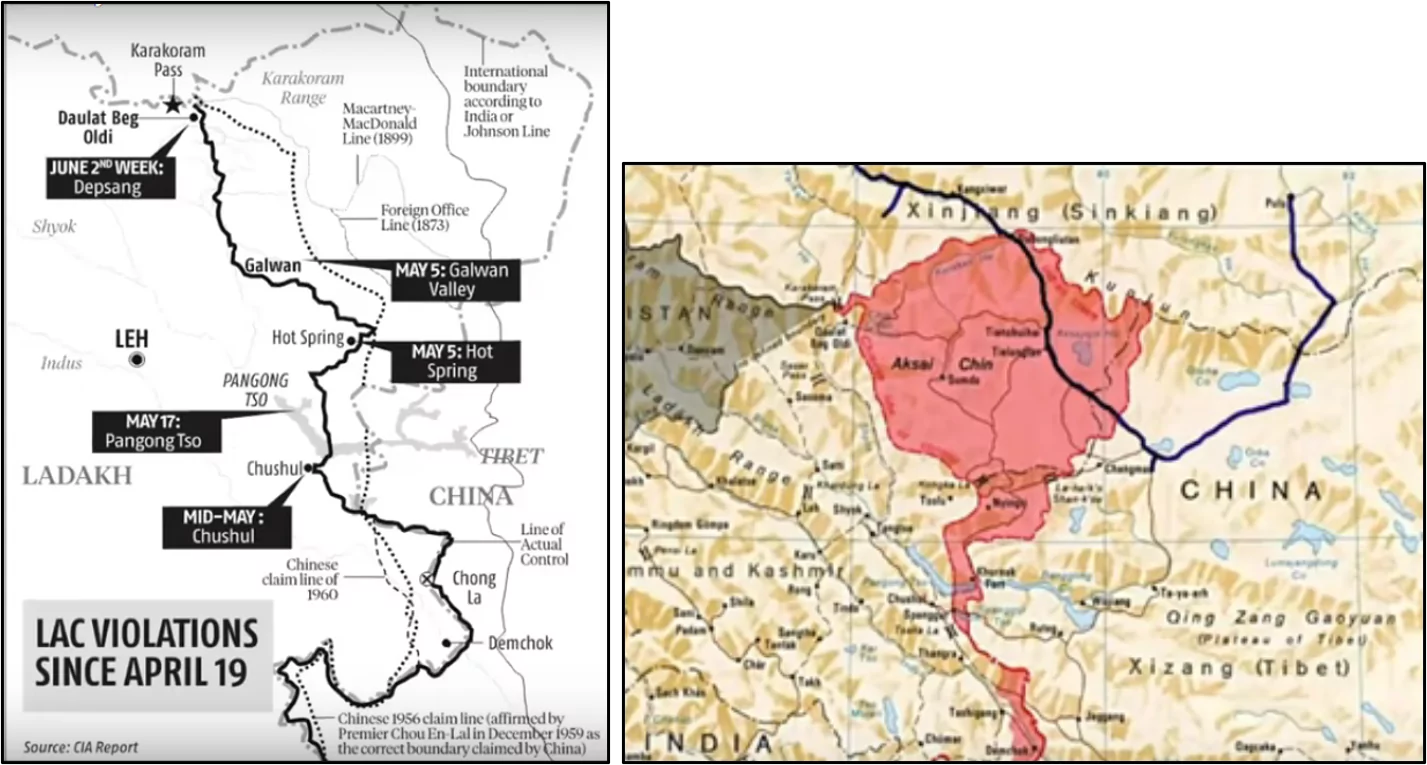

Tension along the LAC in Ladakh has been rising since early May, when Chinese troops began crossing the LAC into the Indian side at various points—including the Galwan Valley, Pangong Tso, Hot Springs, and more recently, at Depsang. Indian soldiers were prevented from entering areas they have been patrolling for decades. Following the bloody clashes at the Galwan Valley in mid-June, tensions soared and both sides stepped up deployment of soldiers and military equipment along the LAC. The possibility of a military confrontation loomed.

On the face of it, the current pullback of troops is a positive development, as it can be expected to reduce tension. However, the nature of the pullback is disadvantageous to India, as New Delhi appears to have ceded to China territory that was, until recently, under Indian control. Not only has China not pulled out of all of the Galwan Valley, but it continues to claim this area. So, what is driving China’s heightened territorial aggression against India in the LAC’s western sector, and why is it seeking control over the Galwan Valley?

The Dispute over Aksai Chin

The entire India-China border is disputed. Not only do the two countries disagree on where the LAC runs, but they also claim chunks of territory under the other’s control. In the eastern sector, China claims 90,000 square kilometers of territory, which is roughly coterminous with the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. In the western sector—which is the focus of the current tensions—India claims 38,000 square kilometers of land in Aksai Chin, which is under Chinese control. India also disputes China’s possession of another 5,180 square kilometers of territory in the Shaksgam Valley that Pakistan ceded to China in 1963.

Aksai Chin’s importance to China rose in the wake of the latter’s invasion of Tibet in 1950-1951. Beijing needed overland routes to transport soldiers, equipment and supplies to Tibet. Of the three routes into Tibet available at that time, the western route from Xinjiang to Tibet was the most convenient. Like the other routes, the western route ran through difficult terrain, but it was an all-weather route that was easier to navigate. However, this route ran through Aksai Chin. Control over Aksai Chin was therefore vital for the PRC’s consolidation of control over Tibet, and in the early 1950s China began construction of a road through the region capable of supporting vehicular traffic. The value of this road, which was completed in 1957, grew in the wake of the 1959 Tibetan uprising as China had to send in large numbers of troops to crush the uprising and tighten its grip over Tibet. The military capture of Aksai Chin became necessary, and this was achieved through the 1962 war with India. [2]

India and Aksai Chin

Although India has never withdrawn its claim over Aksai Chin—it claims Aksai Chin as part of Ladakh and the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, and has always depicted it in maps as part of Indian territory—it was the Indian government’s assertion of this claim with greater vigor in August 2019 that appears to have prompted China’s recent aggression (India Today, June 4). On August 5, the Indian government announced the revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomy, and bifurcated the state into two Union Territories: Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh. The following day, India’s Home Minister Amit Shah reasserted India’s claims in the region in unambiguous terms: “Kashmir is an integral part of India, there is no doubt over it. When I talk about Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and Aksai Chin are included in it” (emphasis added by the author) (The Hindu, August 6, 2019).

India’s Minister of External Affairs S. Jaishankar sought to reassure the Chinese that the August 5 decision had “no implication for the external boundaries of India” or for the LAC, and that “India was not raising any additional territorial claims” (The Hindu, August 12, 2019). However, Beijing was unconvinced and described the Indian decision as a “unilateral move” that “challenges China’s sovereignty” (Global Times, October 31, 2019). Such statements suggest that Beijing suspected India of having “bigger geo-strategic plans” (India Today, June 4).

Strategic Infrastructure Construction Along the LAC

Beijing’s suspicions of India have likely been fueled by India’s growing infrastructure building activity near the LAC over the past decade. [3] Since 2008-09, India has reactivated abandoned airfields at Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO), Fukche, Depsang, and Chumar in Ladakh, and these airfields now serve as landing grounds for Indian Air Force (IAF) transport aircraft. It has also been constructing a network of “strategic roads” near the LAC. Work on these roads has accelerated in recent years, and 61 of the planned 73 roads are in various stages of completion (Economic Times, January 20). Importantly, India has completed construction of the 255 kilometer-long Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) road, which links Leh (the capital of Ladakh) with DBO, India’s northern-most post (located just 9 kilometers south of the Karakoram Pass that separates Ladakh from Xinjiang) (Economic Times, June 8).

Its development of infrastructure near the LAC has improved India’s capacity to defend its borders. In the past, Indian forces relied on dropping supplies via helicopter to soldiers deployed near the LAC. However, they are now able to ferry troops, and even tanks, by C-17 Globemasters and C-130 Super Hercules aircraft to landing strips at DBO and other places (The Tribune, June 29). As for the DSDBO road, it is an all-weather road and runs almost parallel to the LAC. It enables India to transport troops and equipment overland right up to the strategic point of DBO. Since the road runs almost parallel to the LAC it facilitates a lateral movement of troops. As stated by a senior officer of the Indian Army, “Feeder roads that are being built from the DSDBO road to forward posts near the LAC will help movement of troops closer to the LAC. The need for soldiers to undertake arduous treks has reduced and mobilization up to the LAC will be faster.” [4] Importantly, the DSDBO road “significantly improves India’s position in the local balance of forces,” especially since China “lacks a road similar to the DSDBO that runs parallel to the LAC” (The Hindu, May 27).

The improvement of border infrastructure has enhanced India’s capacity to defend its territory—but also, “worryingly for China, to carry out offensive operations.” [5] Indeed, since 2014, India has “adopted a more ‘assertive posturing’ to ‘interdict’ Chinese troops” (The Tribune, May 28). It is in the context of an increasingly assertive India and its improving border infrastructure that the Indian Home Minister’s statement last year, reviving a largely dormant claim over Aksai Chin, would have triggered apprehension in Beijing.

Implications for CPEC

It is likely that China is concerned as well over the DSDBO road’s potential implications for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship component of its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. The corridor, which links the Pakistani port city of Gwadar to Kashgar in Xinjiang, traverses Gilgit-Baltistan, a part of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir. This is territory that India claims, and New Delhi has strongly opposed CPEC on grounds of the corridor running through Gilgit-Baltistan (Deccan Herald, May 14). While reiterating its claim over Aksai Chin last year, the Indian Home Minister also mentioned Pakistan Occupied Kashmir as being part of India. Gilgit-Baltistan was subsequently included in the declared Union Territory of Ladakh (Deccan Herald, November 3, 2019). Earlier in 2016, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had spoken of the need to draw the world’s attention to the grave human rights situation in Gilgit-Baltistan, prompting fears in Pakistan and China that India would stir trouble in the restive region, and possibly sabotage CPEC projects (Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, September 29, 2016).

For China, any attempt by India to destabilize Gilgit-Baltistan or wrest control over this region would be disastrous for CPEC. Gilgit-Baltistan lies to the west of DBO, and it is likely that India’s development of landing facilities at DBO and other places in Ladakh—as well as construction of the DSDBO road—has worried China, as these developments could pose a threat to its substantial interests and investments in Gilgit-Baltistan.

The Threat to Indian Road Connectivity

Although China’s infrastructure building on its side of the LAC has gone on for decades and has far outpaced that of India, it has objected to India engaging in similar activity (The Hindu, May 7, 2013). It has sought to pressure India to halt infrastructure building through incursions into Indian held territory. In April 2013, for instance, some 40 PLA soldiers intruded 19 kilometers into the Indian side of the LAC at DBO. Indian and Chinese soldiers clashed repeatedly, and it was only three weeks later, after India agreed to demolish bunkers in the Chumar sector, that PLA soldiers withdrew (Economic Times, May 7, 2013).

Unlike in the past, when tactical objectives drove Chinese incursions, this time it seems that Beijing is aiming at unilaterally altering the LAC. It aims at taking control of the Galwan region. From its perch on the ridges surrounding the Galwan Valley, the PLA will be able to monitor the DSDBO road and rain artillery and missile fire down on it. This would cut off the Indian Army’s lone overland access to DBO. The PLA is keen to dominate the DSDBO road “permanently”—and to this end, wants control over the Galwan Valley (Business Standard, June 3).

China’s Claims over Galwan

Through its incursion into the Galwan Valley in May, the PRC lay the foundation for taking control over the area. Following the face-off in June, it has laid claim to the area. The day after the clashes, the spokesperson of the PLA’s Western Theater Command, Senior Colonel Zhang Shuili, asserted that China has “always” exercised “sovereignty over the Galwan Valley region” (Global Times, June 16). Since then, China has repeatedly said that the Galwan Valley lies on its side of the LAC (CGTN, June 24).

The last time the Galwan Valley witnessed fighting was during the 1962 war. Although the LAC has witnessed clashes from time-to-time, the border at the Galwan Valley has been peaceful, as the LAC here was not disputed. This was because the two sides had accepted that the Galwan Valley was on the Indian side of the LAC (Business Standard, May 23). That has now changed, with the Chinese claiming sovereignty.

India has rejected the Chinese claims as “exaggerated and untenable,” and maintained that the “position with regard to the Galwan Valley area has been historically clear” (Times of India, June 21). Hitherto, Indian troops have been patrolling around PP 14, but under the “mutual disengagement” agreement are pulling back 1.8 kilometers from this point. India has pulled back from territory it controlled for decades, and by agreeing to the mutual pullback from the Galwan Valley, the Indian government has ceded ground to the Chinese. The Modi government seems to have “aided and abetted” China’s land grab in Ladakh (Business Standard, July 7).

Conclusion

There are lessons that India should draw on from previous experiences with disengagement agreements with China. An agreement on the “expeditious disengagement” of troops from the standoff site near Doklam that was reached in August 2017 ended that crisis. However, a few months later, satellite images available in the public domain revealed that Chinese soldiers were back and building military structures, including helipads and a full-fledged military complex, near the site of the standoff (NDTV, January 17, 2018). More recently, on June 6 Indian and Chinese military officials agreed to pull back from the Galwan Valley. The Chinese did not do so, and when Indian soldiers went to check out the ground situation on the night of June 15, they were ambushed by PLA soldiers. A brutal and bloody face-off ensued, triggering a sharp surge in bilateral tensions. India will need to remain on guard to prevent this history from repeating itself.

Dr. Sudha Ramachandran is an independent researcher and journalist based in Bengaluru, India. She has written extensively on South Asian peace and conflict, political, and security issues for The Diplomat, Asian Affairs and the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor and Militant Leadership Monitor.

Notes

[1] Graphics taken from the Jamestown Foundation webinar, “Face-Off in the Himalayas: China’s Active Defense and India’s Reaction” (June 29, 2020), presentation of Ajai Shukla. https://jamestown.org/event/webinar-face-off-in-the-himalayas-chinas-active-defense-and-indias-reaction/.

[2] John W. Garver, Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century, New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2001.

[3] For decades, India refrained from building roads and other infrastructure on its side of the LAC for fear of drawing Beijing’s ire. Moreover, India’s security establishment was of the view that building roads up to the LAC would facilitate a PLA advance into the Indian plains in the event of war. That thinking changed in 2006, when India’s Cabinet Committee on Security decided to construct 73 ‘strategic roads’ near its borders (China Brief, September 13, 2016).

[4] Author’s Interview, Retired Lt. Colonel of the Indian Army’s Northern Command, New Delhi, June 29.

[5] Ibid.