Beijing Doubles Down on Kim Dynasty

Publication: China Brief Volume: 12 Issue: 16

By:

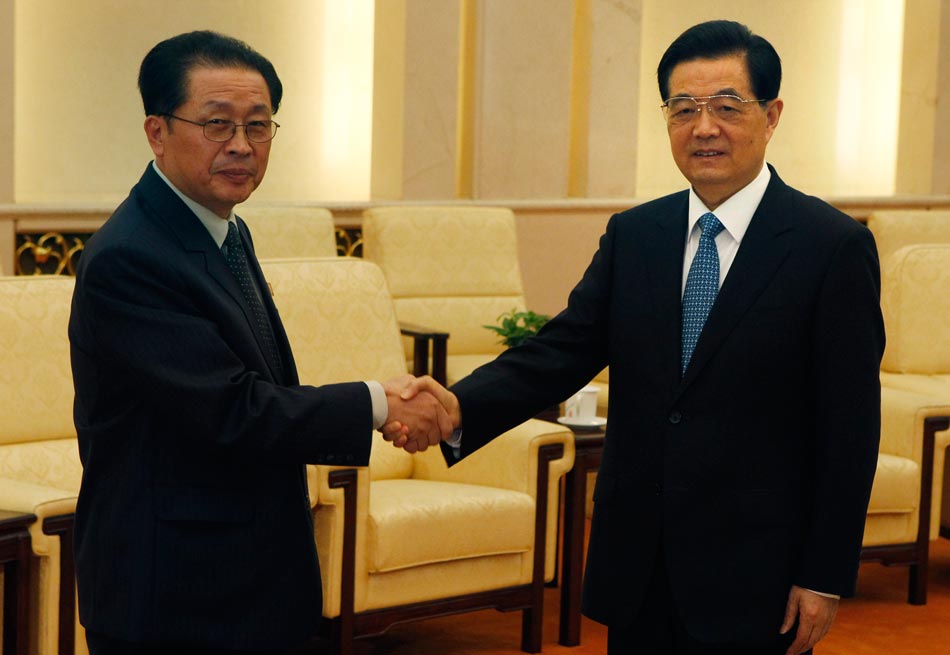

Following months of confused signals regarding the relationship between China and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK or North Korea), it now looks like their ties has weathered the recent DPRK leadership transition and could even strengthen in coming months. Jang Song-thaek, director of the central administrative department of the DPRK’s ruling Workers’ Party of Korea, is on a six-day visit to China designed to revitalize economic relations between the two governments while they consolidate their complex leadership transitions (Xinhua, August 14). During Jang’s visit, China and North Korea announced Beijing will boost its investment in the north through two economic zones, building on a series of high-level meetings this spring.

High-level meetings between senior Chinese and DPRK leaders, disrupted by Kim Jong-il’s death last December, have only recently resumed. During his last year in power, Kim Jong-il, who disliked travelling, made three visits to China in what seems a successful effort to secure Beijing’s acceptance of his plans to transfer power to his youngest son, Kim Jung-un, who is thought to have been in his twenties [1]. From April 5–6, a People’s Liberation Army delegation led by Major General Qian Lihua, director of the Ministry of National Defense Foreign Affairs Office, met Kim Yong Chun, vice chairman of the DPRK National Defense Commission and Minister of the People’s Armed Forces. Later in April, DPRK Vice Minister Kim Yong Il travelled to Beijing, where he met with President Hu, State Councilor Dai Bingguo, Organizational Department head Li Yuanchao and International Liaison Department head Wang Jiarui (China Daily, August 15). Wang himself became the first senior foreign official to meet Kim Jong-un during his July 30–August 2 trip to North Korea. He reportedly urged the DPRK not to launch more long-range missiles or conduct another nuclear weapons test, at least until China had completed its political transition later this year (Washington Times, August 16; Xinhua, August 15).

Beijing oosting Investment in North Korea

During Jang’s visit, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce issued a statement affirming that Chinese investment in the DPRK and other economic links between the two countries will grow significantly in coming years. The main driver will be the renewed commitment of both states to develop two special economic areas—the Rason Economic and Trade Zone and the Hwanggumphyong and Wihwa Islands Economic Zone—created to entice foreign direct investment to the DPRK (China Daily, August 15; Xinhua, August 14). Jang, considered one of the key powers behind the throne in Pyongyang, co-chaired an August 14 meeting of the zones’ organizing committee in Beijing, along with Chinese Minister of Commerce Chen Deming (Xinhua, August 15; Korea Herald, August 15; Global Times, August 14).

In his presentation at this year’s Jamestown China Defense and Security Conference, John Park, an expert on China-DPRK economic relations, asserted that Beijing has undertaken a major campaign to preserve stability in North Korea since the nadir of their bilateral relationship in 1992, when DPRK leaders complained about Beijing’s moving closer to South Korea. China helped North Korea recover from its disastrous flood and famine a few years later. Beijing has since been encouraging the DPRK to introduce Chinese-style economic reforms while also helping it build the state capacity needed to implement them. For example, while Beijing deemphasized food aid and other one-way transfers, Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have helped Pyongyang develop its natural resource and mining sectors by investing large sums of money, equipment and other resources in North Korea as well as training local workers and managers.

During his visit to China in August 2012, Jang Song-Thaek expressed hope that the Chinese government would provide over $1 billion worth of loans to help develop and reform North Korea’s economy (Chosun Ilbo, August 14). Wang said the Chinese government would consider this request, but would like North Korea to commit to using the additional funds for economic reform rather than military spending (Zaobao.com, August 14, 2012).

In addition to reducing the risk of state failure in a neighboring state, Beijing benefits through its investments and local capacity building by securing large quantities of coal, iron ore and other minerals from North Korea at prices often much lower than those on global markets. These growing economic ties with the DPRK in conjunction with China’s interest in North Korean stability give many Chinese a major stake in averting additional sanctions and not antagonizing Pyongyang so that the DPRK does not retaliate against Chinese economic interests (Yonhap News, August 9). Even so, at some point the Chinese leadership may need to choose between bolstering the DPRK’s economy and securing its natural resources at bargain prices.

The Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency estimates Sino-DPRK two-way commerce reached a record $5 billion in 2011. China’s main exports included automobiles, minerals and machinery to North Korea while importing minerals, timber and natural resources—including so-called rare-earth metals [2]. China also provides North Korea with unilateral food aid, fuel and emergency humanitarian assistance. Beijing is letting at least some 40,000 North Korean laborers work in China and paying most of their wages to the cash-strapped DPRK government. This unprecedented decision is risky since the workers probably compete directly with China’s own unskilled labor pool. Many Chinese already resent what they see as excessively generous support for ungrateful North Koreans—a sentiment stoked by North Korean pirates’ recent seizure and mistreatment of Chinese fishermen (Los Angeles Times, July 1).

Some of China’s independently-minded SOEs also supply dual-use assistance to the DPRK that can strengthen its military. For example, earlier this year, Pyongyang paraded new transporter erector launchers for its missiles that appear to have been supplied by China’s Wanshan Special Vehicle Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of the politically influential China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation [3]. In April 2012, U.S Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta told Congress that the U.S. government has evidence of continuing Chinese assistance to the DPRK missile program despite UN sanctions (BBC, April 24). On June 29, a UN panel issued a public report finding that, of North Korea’s 38 alleged violations against the UN Security Council resolutions, 21 involved China (Aboluowang.com, July 1). The collapse of intra-Korean economic relations since the conservative government in Seoul cancelled many bilateral commercial projects after coming to power in 2008 has reinforced China’s economic primacy in the north.

Nonetheless, official two-way investment is quite low. According to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, investment in the DPRK’s non-financial sectors amounted to only $300 million by the end of 2011, while total North Korean investment in China was merely some $100 million (China Daily, August 15). One unnamed Chinese businessman said that at least 8,000 Chinese business people work in the DPRK. Although he cited cheap labor as one advantage of doing business there, he complained inefficient DPRK infrastructure delays deliveries and undermines a business’ reputation. As part of its economic capacity-building efforts, Beijing has been hosting training courses for the zones’ DPRK managers as well as investing in the DPRK’s physical infrastructure. Commenting on the August 14 agreement, Zhang Dongming, a Korean affairs expert at Liaoning National University, confirmed China is building DPRK capacity to help develop its economy: "Formulating economic policies according to its national conditions is the most important task for North Korea now and training management officials is critical to achieving this goal" (Global Times, August 14).

Increasing investment from these low levels should not be difficult, but until recently the political uncertainties regarding the DPRK’s political transition and its relationship with China might have been discouraging investors. Immediately after Kim Jong-il died last December, the Chinese media broadcast the unease of Chinese experts regarding the situation. For example, Han Zhenshe of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences discounted the prospects of a near-term change in North Korean foreign policy since the new leadership would be preoccupied with the power transition. Zhang Tingyan, China’s first ambassador to South Korea, speculated that the transition would probably proceed as planned but cautioned “we can’t rule out contingencies” (China Daily, December 20; Global Times, December 19). By January, Chinese media conveyed more favorable and reassuring assessments of the DPRK situation (Asia Times, January 5).

The Limits of Chinese Influence

Chinese analysts and officials probably are sincere when they complain that Beijing’s influence in Pyongyang is limited. For the past few years, China has unsuccessfully sought to revive denuclearization talks, which have not met since late 2008. In March, Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi reaffirmed Beijing’s support for the Six Party Talks, which he described as “an effective mechanism and important platform for discussing and resolving” the nuclear issue as well as for advancing ”the common interests of all parties” (China-U.S. Focus, March 7).

More recently, the limits of Beijing’s influence with the new DPRK leadership become evident in its failed month-long diplomatic campaign to reverse the DPRK’s March 16 announcement that it would launch an “earth observation” satellite on a long-range rocket. Most foreign observers saw the planned launch as also an effort to further develop the DPRK’s long-range ballistic missile capacity—if that was not already its primary purpose. The UN Security Council had prohibited the DPRK from launching further missiles, which had specially alarmed Japanese and U.S. officials since the DPRK seems in the process of developing a nuclear warhead suitable for mating with such missiles. The PRC Foreign Ministry claimed not to have received advanced notice of the DPRK announcement (Korea Times, June 12). Before the April 13 launch attempt, Chinese diplomats held emergency talks with the North Korean Ambassador to China, DPRK Vice Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho and other North Koreans as well as additional foreign representatives. These efforts proved ineffective [4]. Among other problems, the launch became a prestige issue for the North Koreans, who were using it to mark important national anniversaries. In the end, the test proved an embarrassing failure, but the attempt derailed a DPRK-U.S. nonproliferation-and-food aid agreement that, with China’s support, had been negotiated at the end of February 2012.

As in similar crises in 2006 and 2009, Chinese representatives criticized Pyongyang’s actions but also those individuals in Seoul and Washington calling for a hard-line response. Beijing urged restraint following the launch. The Chinese government signaled its displeasure to Pyongyang by, for example, permitting five DPRK refugees who had been confined to the ROK diplomatic mission to Beijing to finally take up asylum in the ROK (Korea Times, June 12). Beijing, however, blocked new Security Council sanctions and would consent only to the council’s rotating president making a statement that criticized the launch and instructed the sanctions committee to look for more measures, which Beijing could use initially to pressure the DPRK from engaging in further provocations but later veto as required. Chinese representatives also have claimed credit for averting a third DPRK nuclear weapons test. The previous two DPRK missile crises, in 2006 and 2009, were soon followed by North Korean nuclear tests. Analysts pointed to evidence that the DPRK was preparing such a test this spring, but then Pyongyang announced it had no plans to undertake a third nuclear test " at present" (China Daily, June 19).

China remains North Korea’s most important foreign diplomatic, economic and security partner, but its willingness to employ these assets to pressure the DPRK is limited by several considerations. Despite their irritation with the DPRK regime, most Chinese officials appear more concerned about the potential collapse of the North Korean state than about its leader’s intransigence on the nuclear and missile questions. Beijing fears North Korean disintegration could induce widespread economic disruptions in East Asia; generate large refugee flows across their borders; weaken China’s influence in the Koreas by ending their unique status as interlocutors with Pyongyang; allow the U.S. military to concentrate its military potential in other theaters (e.g. Taiwan); and potentially remove a buffer separating their borders from U.S. ground forces. At worst, the DPRK’s collapse could precipitate military conflict and civil strife on the peninsula that could spill across into Chinese territory. Chinese policy makers consistently have resisted military action, severe economic sanctions and other developments that could threaten instability on the Korean peninsula. Beijing has been willing to take only limited steps to achieve its objectives. These measures have included exerting some pressure—such as criticizing DPRK behavior and temporarily reducing economic assistance—but mostly have aimed to entice Pyongyang through economic bribes and other inducements.

Conclusion

China’s recent commitment to provide additional economic aid to North Korea confirms that, despite mutual tensions and Beijing’s concern aboit Pyongyang’s roguish ways, the Chinese leadership has decided to back the new DPRK leadership team. Instead of heeding U.S. advice to impose additional sanctions and pressure on Pyongyang, Beijing has chosen to apply more positive levers of influence—trade, investment and capacity building. China’s logic may be that it needs to rebuild its leverage in North Korea now in order to have some means of credibly threatening to withhold benefits later to discourage future DPRK provocations. At present, Beijing’s tools of influence are insufficiently flexible; threats to cut off food or fuel aid lack credibility since they could precipitate a North Korean collapse, Beijing’s worst nightmare. China, however, is undergoing its own leadership transition, raising the prospect that the DPRK will reconsider its own China policies in coming months.

Notes:

- Shamshad A Khan, “”China’s Relations with Japan, Koreas: Measured Caution,” in Mandir Singh, ed., China Year Book 2011, New Delhi: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, May 2012, p. 81.

- Scott Snyder and See-won Byun, “China-Korea Relations: China’s Post-Kim Jong Il Debate,” Comparative Connections, May 2012.

- Mark Hibbs, ”China and the POE DPRK Report,” Arms Control Wonk, July 2, 2012, https://hibbs.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/879/china-and-the-poe-dprk-report.

- Snyder and Byun, “China-Korea Relations: China’s Post-Kim Jong Il Debate.”