Beijing Learning Lessons From Russian Response to Financial War

Publication: China Brief Volume: 25 Issue: 14

By:

Executive Summary:

- Beijing has tracked Russia’s response to what it perceives as financial warfare from the United States and its allies and has begun mitigating its vulnerabilities and building an offensive toolkit in response. Chinese experts take confidence from Moscow’s resilience in face of more than 21,000 sanctions imposed since February 2022, and also quietly praise Russia for accelerating the internationalization of the renminbi (RMB).

- The PRC now is prioritizing financial security over maximizing investments returns, pursuing reserve diversification, capital controls, anti-sanctions legal instruments, and accelerated development of alternative infrastructures like the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) and a digital currency–based settlement platform, Project mBridge.

- Dedollarization has been helped by Russia’s use of the RMB for energy, commodities, and bond issuance, as well as for some trade with partners like India and Brazil. Hong Kong also plays a central role, and has become a testing ground for Beijing’s financial reforms.

- Despite progress, the RMB accounts for a small proportion of global payments. Without full capital account liberalization, its credibility and usability remain constrained—posing a core dilemma between financial openness and domestic control that Beijing has yet to resolve.

Three years after the United States and its allies imposed sweeping financial sanctions on Russia following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it is clear that war is now waged as much with code, currency, and clearing systems as with conventional weapons. Financial and economic tools can be mobilized with unprecedented speed and scale to hold authoritarian regimes accountable.

For the People’s Republic of China (PRC), this form of financial warfare has provided monitory lessons, prompting the government and its financial security apparatus to assess whether their financial system can endure and respond to similar actions. Research from official and academic institutions, as well as economists from top research and finance institutes, has mapped financial vulnerabilities and explored resiliency and contingency strategies, and reveals a growing sense that the PRC’s financial system must be elevated to the same strategic level as military, diplomatic, and broader economic planning.

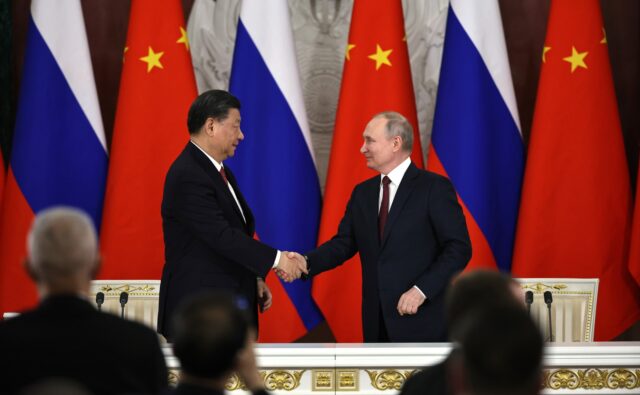

Some of Beijing’s actions taken as a result of this work are beginning to bear fruit. At the 17th BRICS Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov praised the growing use of national currencies in trade, calling it a “reliable, independent” alternative to Western financial systems. With Russia–PRC trade now largely settled in rubles and renminbi and bilateral volumes reaching $245 billion last year, momentum behind dedollarization is real (Sina, July 6).

PRC Sees Successful Russian Response to Financial Sanctions

For Chinese analysts, the most alarming part of the U.S. and allied sanctions package—including more than 21,000 sanctions on Russian individuals and entities—was the freezing of $300 billion in Russian central bank reserves. Previously, such a move was considered untouchable, even at the height of the Cold War. The result was capital flight, ruble depreciation, and rising inflation (Castellum, January 19). Experts from the Central Party School called this a fundamental shift in international finance, signaling that no foreign reserve held in the West is secure if strategic interests diverge. [1] Russia’s National Settlement Depository was blocked from making payments in dollars and euros, while major banks were removed from SWIFT—the global interbank messaging network (see EDM, May 1, 2024). Chinese scholars concluded that SWIFT had lost neutrality and become a tool of American economic coercion. [2]

Chinese experts also highlight the strategic intent behind these measures. As analysts at the PBOC’s Financial Research Institute (中国人民银行金融研究所) argue, modern U.S. sanctions are designed not just to punish but to deter—by showcasing the asymmetric power embedded in global financial infrastructure. [3] In the Russian case, unprecedented sanctions have driven up domestic inflation and increased the risk of corporate bankruptcies, delivering widespread and structural shocks to Russia’s economy and employment (see Strategic Snapshot, March 13).

One unexpected takeaway from many Chinese analysts is the ultimately limited impact of the sanctions. Russia’s economy has not collapsed under pressure. Instead, Moscow has mounted a resilient and adaptive response. The ruble recovered much of its value in the year following the invasion and in July 2025 is nearly half as weak as its historical low in March 2022 (Trading Economics, accessed July 9). While still weaker than pre-war levels, Chinese commentators see the ruble’s rebound as a testament to the effectiveness of Moscow’s proactive response.

Foremost among those actions were strict capital controls. Chinese sources widely praise the Kremlin’s rapid imposition of foreign exchange restrictions, mandatory ruble conversions of export earnings, and temporary bans on divestment by foreign investors. Moscow also raised reserve requirements for dollar deposits, restricted capital transferal, tightened lending conditions for foreign currencies, and banned most foreign currency payments. These steps, in their view, bought Moscow time to stabilize its financial system and prevent mass capital flight. [4]

Another measure closely watched in Beijing was Russia’s move to demand that other countries make energy payments in rubles (see EDM, January 27). Scholars from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences interpreted this as an effort to construct a “commodity-backed ruble” (商品锚定卢布)—a bold attempt to reassert monetary sovereignty by tying the national currency to essential exports. While acknowledging the limited and short-term impact of this measure, Chinese analysts nonetheless view it as a symbolically powerful step toward economic self-reliance. [5]

Perhaps the most consequential development, in the Chinese view, was Russia’s pivot to the renminbi (RMB). Across the board, Chinese analysts credit RMB usage with helping Russia maintain liquidity, finance trade, and preserve foreign reserves. Hong Kong has played a pivotal role in supporting Russia’s access to offshore RMB and advancing the internationalization of the RMB in the process. By mid-2023, the RMB had overtaken the euro as the most traded foreign currency in Russia. For many in the PRC, this shift validated the RMB’s strategic potential as a reserve asset and sanctions-resistant currency, especially in bilateral trade outside the Western orbit. [6]

On the retail and payment front, the adoption of UnionPay (银联) following the exit from Russia of Visa and Mastercard is viewed as a practical example of Chinese financial infrastructure and products filling a geopolitical vacuum. Demand for UnionPay cards surged tenfold in the early months of 2022, prompting the largest Russian state-owned and private banks (Sberbank and Alfa-Bank), both of which are sanctioned by the U.S. government, to begin issuing co-branded UnionPay cards for use domestically and abroad (Treasury, April 6, 2022) [7] Despite Chinese analysts regarding this as a positive development, reporting suggests that take-up of UnionPay cards in Russia ultimately has been limited. Fewer banks have accepted cards, and Russians have faced issues using the cards both at home and abroad, largely due to the Chinese banks’s latest hesitancy and fears of expanding U.S. sanctions (Financial Times, April 9, 2023; Newsweek, February 28, 2024; The Moscow Times, November 22, 2024). Chinese commentary nevertheless emphasizes Russia’s broader strategy of dedollarization through global partnerships—not only with the PRC, but also with other countries—as a successful response to U.S. sanctions (see EDM, September 27, December 13, 2022, January 8, February 8, 12, 2024, March 10). [8]

PRC analysis must be taken with caution, however. Its narrative of Russia’s financial resilience is based on a selective reading of economic indicators. Many experts are quick to highlight Russia’s short-term stabilization—such as the ruble’s rebound or the shift to RMB trade—but few acknowledge the broader picture of sustained economic decline and extreme difficulties that Russia is facing (see Strategic Snapshot, May 8; see EDM, May 14, June 1). This disconnect suggests that objectivity is compromised by strategic considerations—legitimizing the Sino-Russian partnership while avoiding domestic anxiety over the PRC’s own vulnerabilities.

Russia Accelerates RMB Internationalization

To Chinese analysts, Russia appears to have helped accelerate the emergence of a parallel, RMB-centered financial architecture. As early as 2015, Russian banks—reeling from sanctions imposed after the unlawful annexation of Crimea—began turning to Hong Kong for financing to help domestic companies refinance approximately $117 billion in foreign debt. Gazprombank, Russia’s third-largest bank, applied for a license to provide securities services in Hong Kong, and major state-owned banks like Sberbank and Vnesheconombank signaled similar interest (Bloomberg, July 28, 2015). Despite these early warning signs, the international community failed to formulate a response to prevent Russia from leveraging the PRC’s financial system for sanctions evasion.

Since mid-2022, Russia has further integrated its financial system with that of the PRC. It has issued RMB-denominated sovereign bonds and encouraged corporations to raise capital through Chinese markets—especially via the Saint Petersburg Stock Exchange (SPB Exchange), Russia’s second-largest bourse, which pivoted in 2022 to include nearly 80 Hong Kong-listed Chinese companies, triggering a 76 percent surge in trading volume (Shangyou News, June 17, 2022; Sputnik, December 8, 2022). The first half of 2022 also saw a surge of Russian companies listing in Hong Kong, nearly tripling the figure from the previous year (Liber, October 17, 2022). Russia has also promoted its own System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS) financial messaging system and its Mir payment network, forming local currency swap agreements and partnerships across the world (see EDM, May 1, 2024).

Energy cooperation marked a major milestone. In September 2022, Gazprom and the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) signed an agreement—now implemented—to settle pipeline gas sales through the Power of Siberia pipeline using a 50-50 split between rubles and RMB (Huanqiu, September 7, 2022; Weixin/Heilongjiang Economic and Trade Platform With Russia, September 24, 2024).

Other countries also now settle trade with Russia in RMB. These include Indian coal purchases, Pakistani crude oil purchases, Brazilian fertilizer imports, and a Bangladeshi loan repayment (PBOC Online, February 27, 2023; China Energy, April 18, 2023; Huanqiu, June 13, 2023, November 23, 2023). [9]

PRC Responses Align With Assessment of Vulnerabilities

Surveying the research conducted to date reveals five key areas of vulnerability in the PRC’s current financial system. These include the following:

- Overreliance on the U.S. Dollar: Over 70 percent of the PRC’s $3.2 trillion in reserves are held in Western currencies. As with Russia, these could be frozen in the event of geopolitical conflict.

- Insufficiently Insulated Payment Systems: Beijing remains reliant on SWIFT. Despite investing in an alternative—the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS)—this system is limited in scale and is itself partially reliant on SWIFT’s messaging infrastructure.

- Limited Global Reach of the RMB: RMB internationalization has been only a partial success. Although usage of the currency surged in Russia, it still lacks the global liquidity, legal clarity, and capital account openness required for reserve currency status (Local Financial Governance Research, 2023).

- Exposure of Overseas Assets: The PRC now maintains a massive portfolio of offshore assets, many of which are exposed to multi-jurisdictional legal regimes. These include One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative projects, sovereign wealth investments, and extensive holdings by state-owned enterprises. These could be a liability in the event of coordinated direct and secondary sanctions (Future and Financial Derivatives, April 2022). [10]

- Institutional Gaps in Financial Crisis Planning: The PRC’s response architecture is fragmented and lacks a national-level financial security coordination mechanism, unlike Office of Foreign Assets Control and the National Security Council in the United states. [11]

In light of these vulnerabilities—and following analysis of Russia’s response—the PRC clearly sees a counterstrategy for financial coercion as necessary. Experts believe this should be built on a robust legal framework and macro-level planning, and operationalized through mapping out tiered response scenarios, stress-testing critical sectors. This could be managed by a new centralized financial security commission. Such a body could simulate SWIFT cutoff scenarios, model reserve freezes, coordinate emergency responses across financial regulators, and help safeguard PRC’s monetary and legal interests abroad [12] The hope is that by building a functional monetary fortress in peacetime (做到平战结合), the PRC might deter sanctions in a time of crisis (Financial Minds, February 2024).

Policymakers have been implementing a multi-pronged financial security strategy in response that largely aligns with experts’ recommendations. The country is slowly reducing its holdings of U.S. treasuries—now down over 27 percent from mid-2022 and 2024—while increasing allocations of gold, IMF special drawing rights (SDRs), and RMB-denominated bonds in politically neutral jurisdictions (World Journal, February 20; Financial Times, May 2; Baijiahao, June 18; CSSN, July 18). This suggests that survivability, not returns, is now being prioritized. [13]

Authorities also have intensified regulatory intervention to manage capital outflows and stabilize domestic markets. The PBOC and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) recently tightened oversight of outbound capital, especially scrutinizing overseas share sales and cross-border transfers tied to Hong Kong, in a bid to prevent capital flight (Reuters, February 27). The PBOC also reinstated a 20 percent foreign exchange risk-reserve requirement on forward sales to discourage speculative hedging and reduce pressure on the RMB—part of a wider set of currency control measures apparently deployed over much of the last year (Bloomberg, January 9; CFR, July 16).

On the equities front, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) adopted a series of defensive measures in 2024 to contain volatility to prepare for potential contingencies. These included a temporary ban on securities lending to curb short-selling and direct appeals to major institutional investors to reduce or pause net selling during market downturns (Financial Times, February 6, 2024; People’s Daily, July 10, 2024).

An emerging legal framework seeks to proactively deter and counter foreign economic coercion. At the center of this framework is the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law (反外国制裁法), passed in June 2021 and modified in 2025 (China Brief, July 7, 2023; State Council, March 23). This legislation authorizes the PRC to impose retaliatory sanctions against individuals, entities, and institutions that enforce or support foreign sanctions against PRC interests. Complementing this are the Unreliable Entity List (不可靠实体清单制度) and administrative rules issued by the Ministry of Commerce and the State Council. Together, these provide legal cover for Chinese firms to refuse compliance with extraterritorial measures while deterring international actors from participating in what Beijing deems unjustified sanctions regimes.

CIPS usage is also growing, allegedly processing RMB 123 trillion ($17 trillion) across 119 countries in 2023 (PBOC, April 12, 2024). Most recently, CIPS signed a memorandum of understanding with the central bank of the United Arab Emirates in May to boost cross-border payment cooperation and develop a program for RMB clearing services across the Middle East and North Africa (Global Times, June 18).

Experiments with digital currency are ongoing. Project mBridge, announced in 2022 and developed by central banks from the PRC, Hong Kong, Thailand, United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, has introduced a digital currency–based settlement platform supporting 15 cross-border use cases such as supply chain finance and trade settlement (BIS, October 26, 2022; China Brief, November 10, 2023). The project is also a vehicle to promote the digital RMB (e-CNY) and broaden RMB application in commodity pricing, futures, swaps, and consumer markets (Ledger Insights, June 18). Adoption remains limited, however, due to regulatory fragmentation and technical inconsistency, prompting calls to strengthen its scalability and integrate with regional economic partnerships.

Hong Kong has emerged as a critical offshore hub to support RMB use. In 2023, settlement services were launched to promote CIPS and the usage of RMB for daily transactions and trades, and a swap line between the PBOC and HKMA was upgraded to a permanent RMB 800 billion ($110 billion) facility. Hong Kong has also announced an RMB 100 billion trade finance facility for offshore banks, benchmarked to onshore rates; expanded bond connect channels; a dual-currency trading mechanism on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange; and RMB clearing banks have been established in 31 countries (Shanghai Securities Journal, January 14). Officials are aware, however, that true RMB internationalization depends on practical usage in trade, capital markets, and commodities, and the RMB—which accounts for approximately 3.8 percent of global market share—still has a long way to go. [14] The lack of full capital account liberalization and greater RMB convertibility will continue to hamper further internationalization. Doing so, however, would expose the PRC’s tightly controlled financial system to external shocks, capital flight, and political risk, undermining the very stability it seeks to protect.

Conclusion

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the sweeping financial sanctions that followed have triggered a paradigm shift in how the PRC understands its financial systems—not just as tools of trade and growth, but as levers of geopolitical coercion.

Chinese experts have expressed overwhelming confidence in response to Russia’s financial resilience, whose experience is being mined, distilled, and repurposed into a roadmap for the PRC’s own economic fortification. The level of internal coordination in translating these lessons into policy is striking, from the push for RMB internationalization and CIPS expansion, to legal and institutional reforms, to cutting U.S. treasury holdings, accumulating gold, launching digital RMB pilots, and strengthening Hong Kong’s offshore financial role. Beijing also is actively exploring ways to weaponize global supply chain interdependence, leveraging foreign reliance on Chinese products.

The central message is clear: financial independence is now being treated with the same urgency as territorial sovereignty. The PRC’s strategic challenge remains twofold, however. It must stay connected to the global financial system while also preparing for scenarios of exclusion. As this dual-track strategy evolves, the United States and its allies must not misread Beijing’s intent. Financial sanctions can only remain effective if policymakers understand how the PRC is adapting. The window to disrupt PRC’s long-term monetary insulation strategy is narrowing, and the time to act is now.

The author would like to thank the Smith Richardson Foundation for supporting this work.

Notes

[1] 郭炜 [Guo Wei] and 薛敏 [Xue Min], 美国对俄金融制裁的演变历程、制裁形式及对中国的启示 [U.S. Financial Sanctions on Russia: Historical Evolution, Sanctions Format, and Lessons for China], 国际金融 [International Finance], 党校(国家行政学院)[Party School of the Central Committee (National Academy of Governance)], (2025).

[2] 李仁真[Li Renzhen] and 关蕴珈 [Guan Yunjia], 俄乌冲突下的SWIFT制裁及其对中国的启示 [SWIFT Sanctions Under the Russia–Ukraine Conflict and Their Implications for China], 国际安全研究 [International Security Review], (2022).

[3] 黄余送 [Huang Yusong], 美国金融制裁评析与对策建议 [A Review of U.S. Financial Sanctions and Countermeasure Recommendations],金融参考 [Finance Reference] (2025), 中国人民银行金融研究所 [Financial Research Institute, People’s Bank of China].

[4] 张蓓 [Zhang Bei], 金融制裁对国家金融安全影响及应对措施 [The Impact of Financial Sanctions on National Financial Security and Response Measures], 国家金融安全 [National Financial Security Journal] (2023), 中国人民银行金融研究所 [Financial Research Institute, People’s Bank of China].

[5] 徐振伟 [Xu Zhenwei], 俄乌冲突下粮油金融危机联动逻辑分析 [Crisis Linkage and Dynamics Among Food, Oil, and Financial Sectors During the Russia–Ukraine Conflict], 经济安全与战略 [Economic Security and Strategy] (2023); 侯蕾 [Hou Lei], 卢布汇率与经济制裁关系研究——以俄乌冲突为例 [The Impact of Economic Sanctions on the Ruble Exchange Rate: A Case Study of the Russia–Ukraine Conflict], 世界经济展望 [World Economic Outlook] (2023).

[6] 许文鸿 [Xu Wenhong], 美欧货币制裁与人民币国际化在俄罗斯的新发展 [U.S.-EU Monetary Sanctions and the New Development of RMB Internationalization in Russia], 欧亚经济评论 [Eurasian Economic Review] (2023).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Guo and Min, supra [1].

[9] Ibid.

[10] 梁潇 [Liang Xiao], 俄乌金融制裁对中国启示 [Lessons for China from Western Financial Sanctions Against Russia], 货币政策参考 [Monetary Policy Insight] (2023); 陈秋雨 [Chen Qiuyu], 从俄乌冲突到金融战及其风险启示 [From the Russia–Ukraine Conflict to Financial Warfare: Risk Lessons for China], 金融风险研究 [Journal of Financial Risk Studies] (2022), 浙江财经大学 [Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics].

[11] 朱海华 [Zhu Haihua] and 高思宇 [Gao Siyu], 金融制裁博弈:俄罗斯与西方 [The Game of Financial Sanctions Between Russia and the West: Strategies, Effects, and Lessons], 国际关系学刊 [Journal of International Relations] (2023) (Eurasian Economy, January 2024).

[12]钟春平 [Zhong Chunping], 金融制裁法律路径与机制及中国海外资产安全保障 [Legal Framework and Mechanisms of Financial Sanctions and Chinese Overseas Asset Security], 法经研究 [Legal and Economic Studies] (2023).

[13] 涂永红 [Tu Yonghong], “人民币国际化发展趋势与香港作为国际金融中心的机遇与挑战” [Trends in RMB Internationalization and the Opportunities and Challenges for Hong Kong as an International Financial Center], 亚太经济 [Asia-Pacific Economic Review], 2024(2). 南洋商业银行与中国人民大学国际货币研究所 [Nanyang Commercial Bank and International Monetary Institute of Renmin University of China.]

[14] 李律仁 [Li Lüren], 建设金融强国:香港助力人民币国际化进程 [Building a Financial Powerhouse: Hong Kong’s Role in Promoting RMB Internationalization], 香港金融论坛 [Hong Kong Financial Forum] (2024).