Beijing’s Calculated Response to NK Missile Launch

Publication: China Brief Volume: 9 Issue: 8

China’s soft and quiescent reaction to Pyongyang’s rocket gamesmanship seems to contradict the image of global statesmanship that President Hu Jintao projected at the G20 summit in London earlier this month. And Beijing’s last-minute agreement to a UN Security Council chastisement of the Kim Jong-Il regime has hardly suppressed suspicions that for ideological and other reasons, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership is still reluctant to handle its trouble-prone neighbor—and staunch ally—with the requisite level of toughness. There are also misgivings that the Hu administration has chosen to treat Pyongyang with kid gloves so that it can play the “North Korean card” in future dealings with United States, Japan and South Korea.

Last weekend, Beijing, together with Moscow, agreed to a watered-down Security Council “presidential statement”—which has less force than a resolution—condemning North Korea for launching the rocket. However, Beijing objected to wording characterizing the gambit as an intercontinental ballistic missile test; it also did not want additional punishments to be meted out to the rogue regime. As a result, the UN document merely called for the tightening of sanctions already applied to North Korea, meaning that the assets of more DPRK institutions would be frozen, and that more goods would be prohibited to be transferred to or from the pariah state. Late last week, China’s UN Representative Zhang Yesui reiterated the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s stance that world reaction to North Korea’s shenanigans must be “cautious and proportionate.” “We are now in a very sensitive moment,” Ambassador Zhang Yesui said at the UN Headquarters. “All countries concerned should show restraint, and refrain from taking action that could lead to increased tension” (AFP, April 13; New York Times, April 12; CNN, April 12).

Within 24 hours of the Security Council statement, Pyongyang announced that it was pulling out of the Six-Party Talks on denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula as a reaction to the UN statement. The Kim regime also said it would “actively consider” resuming its nuclear weapons program, including building a light-water reactor and reprocessing spent fuel rods at an atomic power plant. After Pyongyang’s tantrum- throwing, the Chinese Foreign Ministry again appealed for “calm and restraint” from all sides. “We hope all sides will pay attention to the broader picture, exercise calm and restraint and protect progress in the six-party talks,” said spokeswoman Jiang Yu (New York Times, April 15; Reuters, April 15). This was despite the fact that Pyongyang’s political poker, in addition to Beijing’s vacillations over how to handle its problematic ally, has cast the future of the six-year-old Six-Party Talks into serious doubt.

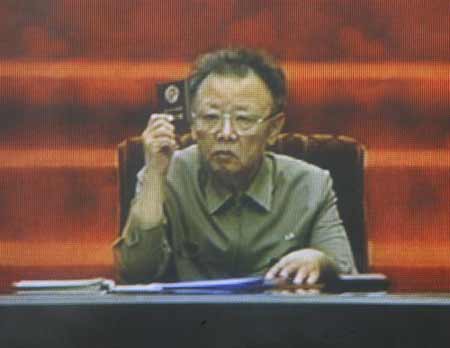

Quite a number of Western analysts have sought to explain Beijing’s tolerance for the Kim regime by citing the CCP leadership’s declining clout with its neighbor. Moreover, the Chinese government is worried about a sudden influx of refugees into its three northeastern provinces, two of which share boundaries with the DPRK (Reuters, April 6; AFP, April 6). Yet there was evidence that just a little over two years ago, a tough Chinese reaction to North Korean brinksmanship did produce results. After the Kim regime detonated a small nuclear device in October 2006, the Hu-led Politburo departed from protocol by issuing a shrill condemnation of Pyongyang’s “brazen” act. Beijing also seconded a no-holds-barred condemnation of Pyongyang issued by the U.N. Security Council. There were also reports that the Chinese leadership threatened to turn off fuel and other supplies to the DPRK. China is Pyongyang’s primary source of foreign economic and technological aid, which amounts to an estimated $200 million a year. Partly as a result of Beijing’s hardball tactics, the Kim leadership promised in early 2007 to put a moratorium on its nuclear program. The reclusive 67-year-old Dear Leader also gave indications that North Korea would follow the “China model” of economic development.

There are signs that Beijing’s North Korean policy has undergone a marked mutation as of late 2008, when both countries designated 2009 as “China-North Korean Friendship Year.” During North Korean Premier Kim Yong-il’s visit to China last month—when news about Pyongyang’s imminent rocket blast had hit the headlines—Kim (not related to President Kim) was zealously feted by Hu and Premier Wen Jiabao, who affirmed Beijing’s comradely ties with the Hermit Kingdom. There is heavy speculation that Dear Leader Kim would pay a visit to China later this year. Last weekend, Hu congratulated Kim’s re-election by the North Korean Parliament as chairman of the all-powerful National Defense Commission (NDC) by highlighting China’s “profound trust” in its neighbor. “It is the consistent policy of the party and government of China to consolidate and develop the Sino-DPRK good neighborly relations of friendship and cooperation,” Hu reportedly said (Xinhua News Agency, April 10; AFP, April 11).

Western analysts on the DPRK have pointed out that a key reason behind Pyongyang’s rocket gambit was to test the reaction of the new Obama administration. Yet Beijing has a similar interest in finding out whether a Washington that is preoccupied with financial woes is able to react with resolve to a challenge in East Asia. In the first few years after 9/11, Hu worked out a kind of quid pro quo with former President Bush: Beijing would help “rein in” Pyongyang in return for Washington’s assistance in preventing then-Taiwan president Chen Shui-bian from seeking de juris independence. Now that the situation in the Taiwan Strait has stabilized after the electoral defeat last year of Chen’s pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party, Beijing may be demanding other American concessions in return for putting pressure on Pyongyang on the weapons of mass destruction (WMD) front (CNN, April 9; New York Times, April 6; Xinhua News Agency, April 8).

Equally significantly, Beijing may want to play a kingmaker role in the forthcoming succession drama in the DPRK. Dear Leader Kim, who reportedly suffered a stroke late last year, is said to be anxious about securing Chinese backing for his third son, Kim Jong-un. Like his two older brothers, the Swiss-educated Kim, 26, does not enjoy the backing of Pyongyang’s generals. Diplomatic sources in Beijing and Seoul said President Kim hoped to secure Chinese blessings for the continuation of the Kim dynasty. The sources said that at this stage, the Hu leadership was studying two options: supporting the younger Kim, or throwing its weight behind a possible “pro-China military strongman or faction.” In the meantime, Beijing wants to improve its ability to influence North Korean politics by not interfering with Pyongyang’s “missile diplomacy.” That Kim is getting serious about the succession issue was evidenced by his appointment of brother-in-law Jang Song Thaek to the NDC last week. There is intense speculation that the role of Jang, who has been given extra powers the past two years, is to ensure sufficient support for one of Kim’s son upon the dictator’s demise (Apple Daily [Hong Kong], April 9; Ming Pao [Hong Kong] April 9; The Associated Press, April 11).

Another reason why the Hu leadership is willing to play ball with Kim is Beijing’s apparent perception that the DPRK has finally decided to pursue a more rational and relatively market-oriented economic policy. Trade between China and North Korea jumped 41 percent to $2.79 billion last year, with most of the surge being increased Chinese exports. Moreover, both state-held and private firms from China have significantly boosted their investments in the Hermit Kingdom. Perhaps more significant is the fact that the Kim team is seriously thinking of reviving plans to turn Sinuiju and the nearby island of Wi Hwa, which are just across the Yalu River to the Chinese city of Dandong, Liaoning Province, into a special economic zone. The Dear Leader discussed the scheme with the ministerial-level Director of the CCP Central Liaison Department Wang Jiarui during the latter’s visit to Pyongyang three months ago. And Wang reportedly pledged special Chinese aid for infrastructure-related projects in this and a couple other proposed zones, including the Chudan Do Island at the mouth of the Yalu River. Seen in this perspective, Beijing might not want heavy Western sanctions against Pyongyang to disrupt the DPRK’s inchoate modernization efforts (Wall Street Journal, April 8; Yazhou Zhoukang (Hong Kong journal), February 22; Korea.net, January 19).

Irrespective of the outcome of Beijing’s two-decades-long efforts to persuade its totalitarian neighbor to emulate China’s reform and open-door policy, however, the Hu leadership is facing tremendous odds. To prove that the CCP leadership is right in obliging concerned countries to adopt a restrained if not conciliatory policy toward the DPRK, Beijing has to pull out all the stops to corral Pyongyang back to the Six-Party Talks framework. The Kim regime, however, has given no sign that it is winding down its ambitious WMD development programs. Nor is it likely that Pyongyang will abandon its time-tested, cynical game of extracting economic and other kinds of aid from the U.S., Japan and South Korea by alternating between postures of thuggishness and relative rationality. Niu Jun, an international relations professor at Peking University agrees that Beijing faces a tall order trying to make the DPRK deliver. “China has been working very hard” in dealings with Pyongyang, Niu said. “I hope China doesn’t [always] need to work that hard in the future,” he said, adding that “China should not make too many promises” to the global community regarding North Korea (Ming Pao, April 6; UPI, April 4).

If, as is likely, the Kim regime perseveres with its long-standing stalling tactics at the Six Party Talks, Beijing stands to be accused of backing the pariah state out of considerations that it can brandish the “North Korean card” to wrangle concessions from countries including the United States and Japan. Even more significantly, the exacerbation of the North Korean threat could give Tokyo a good excuse to beef up its military arsenal, in addition to boosting cooperation with the United States in improving their joint missile defense system. A North Korean faux pas will detract from attempts that Beijing has made to bolster its reputation as a responsible stakeholder on the world stage. Worse, Beijing’s apparent decision to revive its “lips-and-teeth comradely ties” with its roguish ally could make China suffer guilt by association. This, coupled with the quasi-superpower’s enhanced sovereignty disputes with Japan over the Senkaku islands (known as the Diaoyu in China)—and with the Philippines over the Scarborough Shoal (called the Huang Yan Islet by Beijing)—could threaten Hu’s reputation as a peacemaker and a respected elder statesman in the Asia-Pacific Region.