Beijing’s Growing Influence on the Global Undersea Cable Network

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 18

By:

Introduction

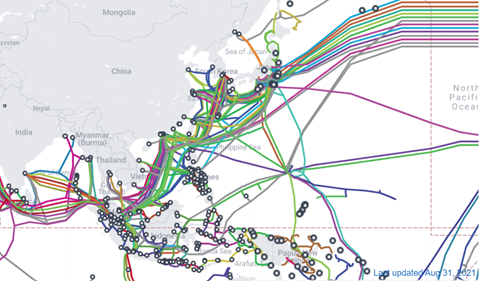

The vast majority of intercontinental internet traffic traverses submarine cables laid across the ocean floor. Private and state-owned firms have long invested in these submarine cables to carry internet traffic and other data, often in cooperation with one another due to the high costs and complex logistics of laying cables undersea. In recent years, Chinese state-owned telecommunications companies have greatly increased their investment in submarine cables; in 2021 alone, three state-owned Chinese telecoms had ownership stakes in 31 newly deployed cables (TeleGeography, accessed August 30). Much of this investment has focused on infrastructure beyond the Chinese mainland.

These Chinese state investments are occurring in the context of growing international concern about Chinese technology practices: specifically, how the Chinese government is working to undermine the global open internet; the degree to which the Chinese government exerts control over Chinese internet companies; and whether the Chinese government’s overseas infrastructure and development projects—broadly represented by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—are a means of spreading surveillance technology and increasing technological dependence on China.[1] In this context, Chinese state investments in submarine cables are especially significant.

Chinese State Investment in Cables

Laying a submarine cable is a costly, complex and logistically intensive process, with the longest intercontinental cables costing hundreds of millions of dollars to build and install (SubTelForum, February 16, 2020). Construction often involves multiple companies (from those making internal fiber to those encasing fibers in metal) and installations can take several weeks of labor. As a result, international companies often make joint investments in cable projects or form consortiums that manage a project across different owners from different countries.

As of December 2020, 383 entities, comprising a mix of private and state-owned enterprises, collectively owned 475 submarine cables deployed globally (Atlantic Council, September 2021). Those involved include traditional telecommunications companies such as AT&T in the U.S. and Airtel in India, as well as newer internet companies like Facebook and Google. They also include state-owned telecommunications and investment firms such as Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd (India), Telecom Egypt (Egypt), and Ethio Telecom (Ethiopia).

Many Chinese investments in the global submarine cable network are directly controlled by the Chinese government. Three Chinese telecommunications companies with investments in submarine cables are entirely state-owned: China Mobile (中国移动, Zhongguo yidong), China Telecom (中国电信, Zhongguo dianxin), and China Unicom (中国联通, Zhongguo liantong). Two other Chinese firms, CITIC Telecom International (中信国际电讯, Zhongxin guoji dianxun) and Companhia de Telecomunicações de Macau (CTM, 澳门电讯, Aomen dianxun), each have ownership stake in a single submarine cable. CITIC Telecom is incorporated in Hong Kong and its parent company CITIC Limited (中国中信服务份有限公司, Zhongguo zhongxin fuwu fen youxian gongsi) is majority-owned by the Chinese state-owned CITIC Group (CITIC Telecom, accessed August 23). Similarly, CTM is incorporated in Macau and its largest shareholder (99 percent) is CITIC Telecom International (CTM, accessed August 23). It is also worth mentioning that a state-owned Chinese electrical company, the State Grid Corporation of China (国家电网公司, Guojia dian wang gongsi), is a member of the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines, a consortium of infrastructure investors from around the world that owns a single submarine cable.

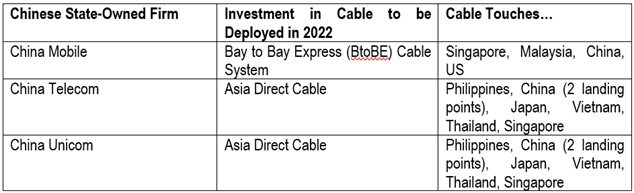

China Telecom has investments in submarine cables that go back decades, including an ownership stake in a cable deployed in 1999 and another deployed in 2016. China Mobile has ownership stakes in one cable deployed in 2020 (TeleGeography, accessed August 30). In the current year, the three state-owned telecoms have substantially increased their investments in new cable projects. China Mobile has invested in at least eight cables that will be newly ready for service in 2021; China Telecom in twelve; and China Unicom in eleven (TeleGeography, accessed August 30). Each of these firms have also invested in cables set to deploy in 2022, giving them additional ownership stakes in the global submarine cable network (see table below).

The three state-owned telecoms—China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom—have all been the subject of United States government national security concerns. From 2019 to the present, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has labeled all three companies a national security risk to the United States, based on its findings that the firms are “subject to the influence and control of the Chinese government” (FCC, May 9, 2019; FCC, April 24, 2020). The logic underlying these concerns is that Beijing’s control of these companies effectively grants it control over the infrastructure that they oversee, which could enable anything from the planting of backdoors in cables as they are built to the interception or disruption of traffic once cables are deployed at the behest of Chinese intelligence or military services. The phenomenon of governments—including the U.S.—tapping into submarine cables to spy is well-documented (Washington Post, July 10, 2013).

According to the FCC, CITIC Telecom International’s ultimate ownership—either by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission or by the Chinese Ministry of Finance—is uncertain, with different publicly available documents providing evidence for each (FCC, March 19). Nonetheless, the Chinese government’s control over both CITIC Telecom and CTM is undisputed. Indeed, the risk concerns about state-sponsored espionage and cyber operations that are outlined above stem from the Chinese government’s control of these submarine cable owners.

Lastly, CNN Philippines has reported on an internal government document, which asserts that the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines—in which the State Grid Corporation of China is a partial owner—is effectively under the Chinese government’s “full control” (CNN Philippines, November 26, 2019). It is difficult to assess the accuracy of such claims, not only because the report in question is secret but also because the exact ownership structures of international consortiums of cable owners can be highly opaque. Yet if such reports are accurate, the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines would be another vector of Chinese state influence in submarine cable investment—as well as increasing security risks around the cable it owns.

Geopolitical Returns on Chinese Submarine Cable Investment

It is important to note that the companies that finance and own submarine cables are not the same as the companies that actually build them, but cable owners’ financial backing provides them the power to decide where a cable is laid, with which areas of the world it is connected, and how fast (speed, bandwidth) to make the connection. As a result, cable owners contribute to the reshaping of the global internet’s physical layout—the constant evolution of servers, cables, and other man-made infrastructure that underpin the internet’s operation.

This matters on the geopolitical level. Determining where cables are laid is a way of influencing how much internet traffic flows over one cable versus another. Traffic routing on the internet is not as simple as selecting the geographically shortest path between sender and receiver, and internet traffic is not necessarily sent along the fastest possible infrastructure route. Traffic routing does tend to favor faster routes over slower ones, which is why laying a new cable—one with higher speed and bandwidth than its neighbors—can be a way for governments to encourage traffic to move across different routes and even through certain borders. Reshaping the internet’s physical traffic can lead to a wide range of benefits ranging from the gradual buildup of technological or economic dependence on a certain company to the interception or disruption of traffic by actors positioned on that cable.

Chinese investment in submarine cables is also tied to the state’s massive BRI capacity-building program, which involves hundreds of billions of dollars in infrastructure spending across dozens of countries (CFR, January 28, 2020). The Digital Silk Road (DSR, 数字丝绸之路, Shuzi sichou zhi lu) was first introduced as an expanded component of the BRI in 2015, and was elevated in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic last year (PRC Ministry of Commerce, August 16, 2020). Its stated aim is to boost international cooperation in the digital economy—which includes developing information infrastructure, promoting information sharing and information technology cooperation, and encouraging internet economic and trade services. In April 2019, Lin Nianxiu (林念修), Vice Minister of the National Development and Reform Commission, said that China had signed Digital Silk Road “cooperation agreements” with more than sixteen countries and launched a “Belt and Road Digital Economy International Cooperation Initiative” with seven others (China Daily, April 27, 2019). But tracking the number of official agreements likely undercounts the DSR’s true reach, with foreign estimates suggesting that more than 40 countries may be participating (The Diplomat, December 17, 2020). Chinese investments in ICT infrastructure in traditionally under-resourced regions such as Africa have also boomed since the DSR’s launch.[1]

Chinese state media has publicized the involvement of Chinese state-controlled submarine cable owners in the Digital Silk Road. For example, China Daily touted China Unicom as a global submarine cable investor, a provider of internet infrastructure services (e.g., cloud computing), and a company with 32 subsidiaries around the world (China Daily, April 27, 2019). In a February 2021 speech, Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that the Chinese government would “accelerate the development” of the Digital Silk Road as part of its “work with other countries to boost global economic recovery and development” (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, February 7).

It is not unusual for companies to invest in submarine cables that do not touch the borders of the country in which they are incorporated. There are many financial benefits for companies who invest in cables in other parts of the world, including expanding connectivity to overseas markets, building out their underlying infrastructure to support products and services (such as cloud data centers), and profiting from licensing cable bandwidth. For this reason, it is not unusual that 36 percent of the submarine cables that China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom have collectively invested in have no landing points in China. But the Chinese government’s explicit focus on digital infrastructure capacity-building around the world raises additional geopolitical questions about these state-owned firms’ decisions to invest in specific cables—as well as what benefits the Chinese government hopes to accrue from them.

Conclusion

There is little to suggest that security risks from these submarine cable investments will recede. Research into ties between the Chinese government’s capacity-building projects abroad and Chinese technology firms’ digital expansion into overseas markets continues. Just in 2020, for instance, a senior China Telecom executive called on the Chinese government to expand and protect its submarine cable network (RFA, June 4, 2020). The Biden administration has also continued investigating ties between Beijing and the Chinese technology sector, and it continues to raise these issues at meetings with allies and partners.

Global society has become greatly more dependent on the internet during the COVID-19 pandemic, and consequently more dependent on submarine cables. As the Chinese government continues investing in physical internet infrastructure around the world, security, privacy, and economic dependence questions tied to those expenditures will only become more geopolitically urgent.

Justin Sherman (@jshermcyber) is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative and a research fellow at the Tech, Law & Security Program at American University Washington College of Law. His work focuses on the geopolitics, governance, and security of the global internet. He has written for The Atlantic, Foreign Policy, Slate, and The Washington Post.

Notes

[1] Some examples of this concern include: Samantha Hoffman, “Engineering Global Consent: The Chinese Communist Party’s Data-Driven Power Expansion,” ASPI, October 14, 2019, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/engineering-global-consent-chinese-communist-partys-data-driven-power-expansion; Maya Wang, “China’s Techno-Authoritarianism Has Gone Global—Washington Needs to Offer an Alternative,” Human Rights Watch, April 8, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/08/chinas-techno-authoritarianism-has-gone-global#; Staff, “The New Big Brother: China and Digital Authoritarianism,” U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, July 21, 2020, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2020%20SFRC%20Minority%20Staff%20Report%20-%20The%20New%20Big%20Brother%20-%20China%20and%20Digital%20Authoritarianism.pdf.

[2] For example, a report by IC Africa notes that Chinese average funding of ICT infrastructure grew from just $399 million between 2012-2016 to announced investments worth $1.1 billion in 2017. See: “Infrastructure Financing Trends in Africa—2017,” IC Africa, 2018, pp.17, https://www.icafrica.org/fileadmin/documents/Annual_Reports/IFT2017.pdf.