Beijing’s Growing Power Over Global Gas Markets

Executive Summary:

- Growing investments by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in liquefied natural gas (LNG) and pipeline infrastructure are increasing its geopolitical influence in energy markets.

- PRC LNG re-exports have increased dramatically from 2022, with re-exports surging nearly 770 percent from 2024.

- Recent progress on the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline and its strong gas partnership with Turkmenistan indicate a desire to deepen ties with Eurasian neighbors.

- The PRC’s gas import diversification strategy is motivated by both economic and geopolitical considerations: bridging the domestic supply gap, securing favorable prices, responding to the U.S. trade war, and developing strategic energy partnerships.

The governments of Russia and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have signed a legally binding agreement to build the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline, according to Gazprom CEO Alexey Miller (Bloomberg, September 2). The pipeline signals deepening energy ties between Beijing and Moscow at a time when the PRC has suspended imports of U.S. liquified natural gas (LNG) in retaliation to President Trump’s tariffs (Bloomberg, March 18; Natural Gas Intelligence, October 29).

Despite steady growth in domestic production, the PRC remains externally dependent on LNG and pipeline gas for around 40 percent of its supply. Beijing’s approach to diversifying suppliers, including with Russia, is motivated by both economic and geopolitical concerns. These include desires to maintain competitive pricing, develop its position as a re-seller of LNG, respond to trade wars, and enhance strategic partnerships with key partners.

Security Concerns Drive Decade of Gas Imports and Production

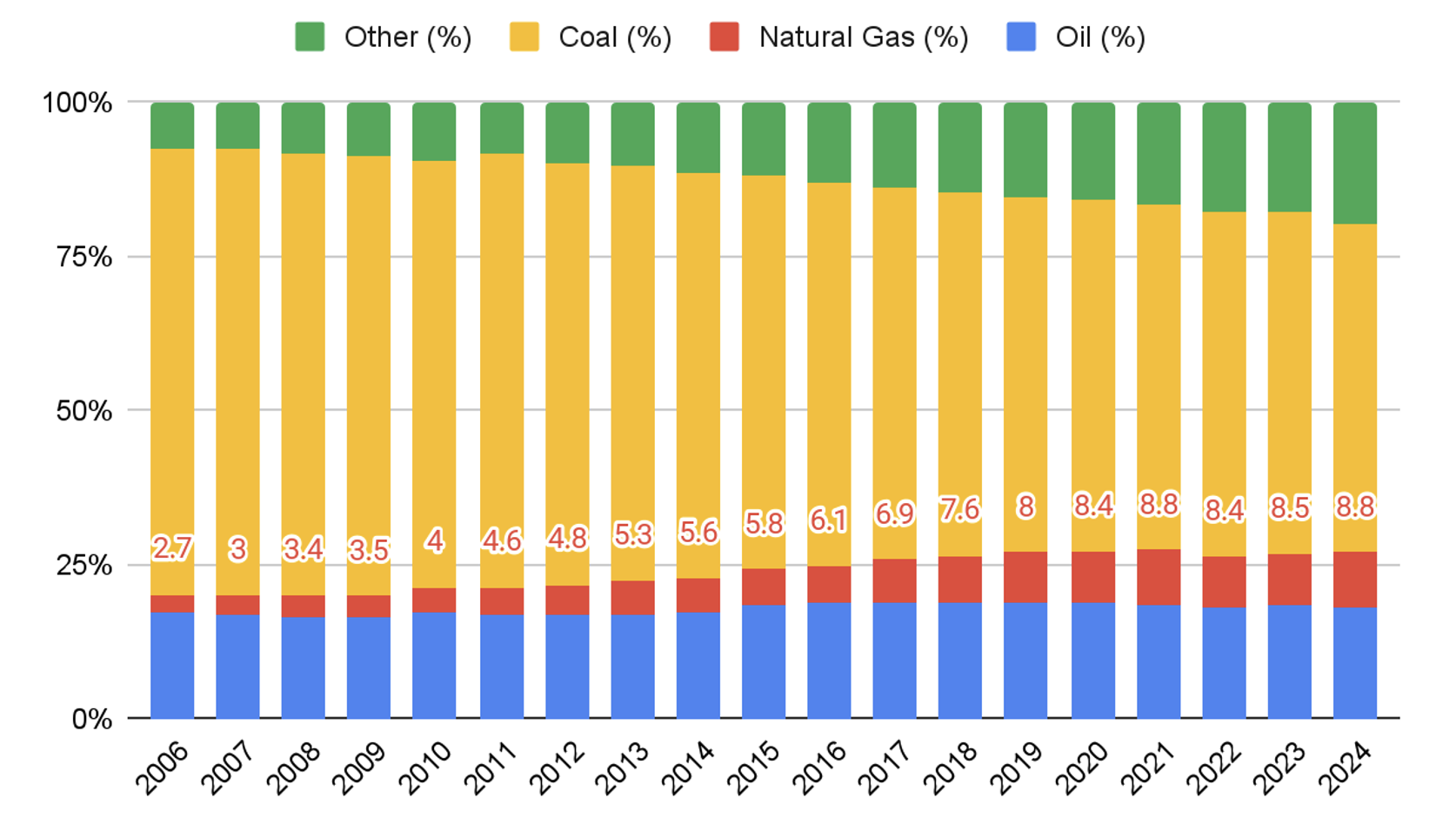

Beijing initially promoted transitioning from coal to gas in 2013 as a means to curb urban air pollution and advance its dual carbon targets (双碳目标) to peak CO2 emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060 (PRC State Council, September 10, 2013). The country’s natural gas consumption has increased significantly since, both in total volume and as a percentage of the national energy mix. In 2024, total demand reached nearly 430 billion cubic meters (bcm), marking an 8.4 percent increase from the previous year. Gas now accounts for almost 9 percent of primary energy use, up from just 2.7 percent when the PRC started to import natural gas in 2006 (National Bureau of Statistics [NBS], February 28).

Figure 1: Natural Gas Continues to Rise as Share of PRC Primary Energy Use

The accelerated fuel transition triggered a supply shortage and price spike in 2017, exposing bottlenecks in infrastructure and production capacity. The State Council responded by tempering its approach, stipulating that the replacement of coal-fired power with gas would henceforth be based on the principle of “letting gas supply determine the pace of [coal-to-gas] conversion” (以气定改). In other words, securing the country’s gas supply before transitioning to coal (State Council, August 30, 2018; Center for Industrial Development and Environmental Governance [CIDEG], December, 2018). Subsequent plans also have stressed close monitoring of “coal-to-gas” (煤改气) progress (National Development and Reform Council [NDRC], March 15, 2023). Gas demand has nevertheless continues to grow across all sectors, rising 8–10 percent year-on-year in 2024, and usage has more than doubled in the last decade (National Energy Administration [NEA], 2024). State-owned oil giant Sinopec projects gas use to reach 610 bcm by 2035 (Sinopec, January 9, 2024).

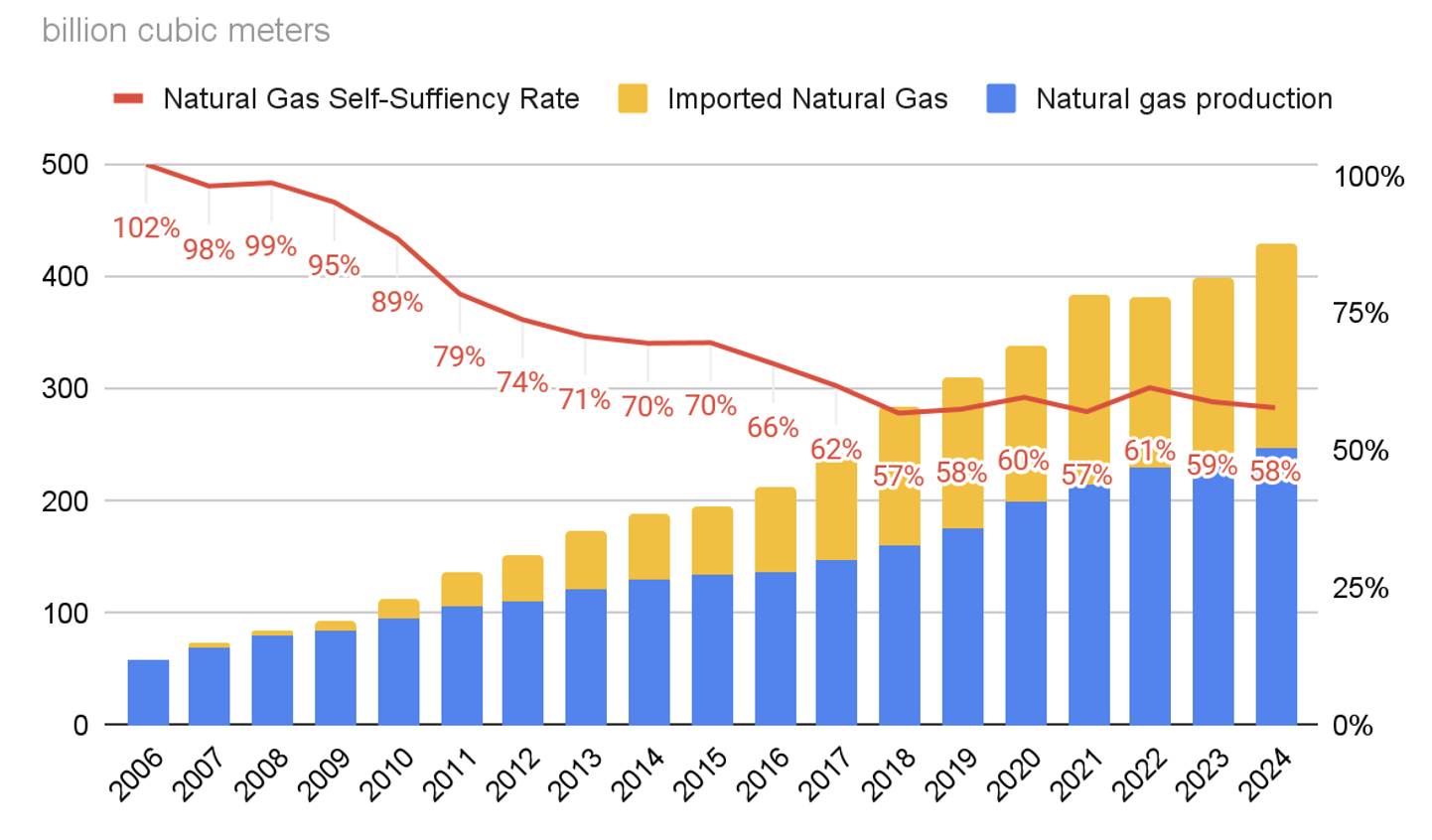

Figure 2: PRC Self-Sufficiency in Natural Gas Sustained at 60 Percent since 2018.

Both high-level statements and the country’s shifting energy mix indicate that concerns over energy security have driven the pivot toward gas. The 2017 supply shock likely only heightened those concerns. Starting the following year, domestic gas production has expanded, rising from 128 bcm in 2014 to 232 bcm in 2024. This is in line with a directive from General Secretary Xi Jinping to “vigorously enhance domestic oil and gas exploration and development to safeguard national energy security” (大力提升勘探开发力度,保障国家能源安全 (Qiushi, December 16, 2020; NDRC, April 27, 2018). Rising production has also been aided by the “liberalize the two ends, control the middle” (放开两头、管住中间) reforms. This strategy encourages market competition while maintaining government oversight across the entire energy sector. In practice, investors and firms handle the production and sales ends of the energy chain, while transmission and distribution remain under government regulation. This has enabled the PRC to maintain a self-sufficiency rate of around 60 percent despite increasing imports (illustrated in figure 2 above). The PRC will allow natural gas consumption to grow as long as this level of self-sufficiency remains above 50 percent (Petroleum University Press, July 21, 2023). In late 2021, Xi emphasized that “the energy ‘rice bowl’ must be firmly held in our own hands” (能源的饭碗必须端在自己手里) (People’s Daily, January 7, 2022).

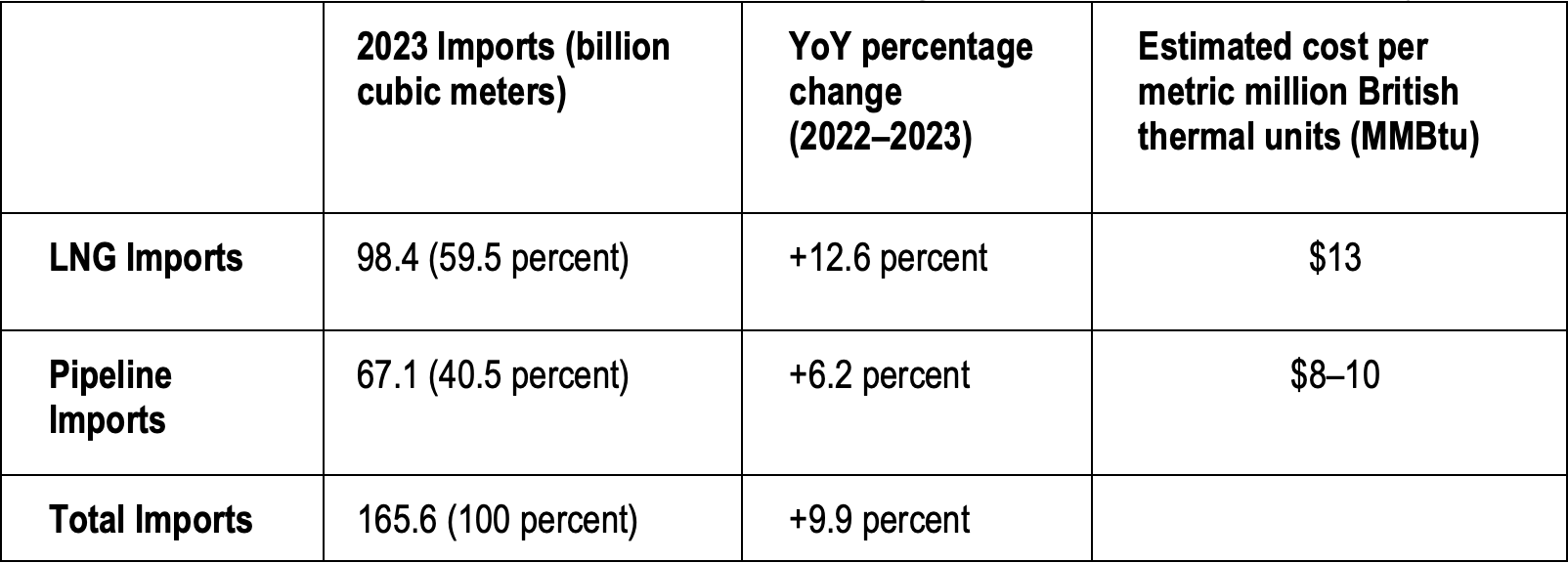

Table 1: PRC imports of LNG and pipeline natural gas have increased in recent years

Dominance in LNG Provides Geopolitical Leverage

The PRC is the world’s top buyer of LNG, which gives it considerable leverage. Most of its LNG comes from Australia (34 percent), Qatar (24 percent), and Russia (11 percent). Only a small portion comes from the United States (5.4 percent) (Baijiahao/Logistics Revelation, February 2).

The country’s LNG infrastructure is extensive. It is home to the world’s largest LNG storage tank in Qingdao, and boasts an LNG carrier fleet that has increased from four ships in 2015 to 59 in 2022 (Xinde Marine News, March 15, 2022; Sinopec, August 25, 2023). This growing capacity boosts supply security, as it helps ensure that domestic needs are met. But it also indicates that the PRC will remain reliant on LNG imports, even if it also allows for flexibility in purchasing and receiving LNG based on market fluctuations. Its capacity is further evident via reports of LNG stockpiling in 2024, during periods when the market was favorable. Intentions to resell likely were the cause of this stockpiling activity (Oil Price, October 7, 2024). In parallel, reports of the PRC’s oil stockpiles indicate a similar strategy of buying when prices are low, but the motivations for oil stockpiles appear to be in order to maintain supply rather than to resell (Reuters, October 4).

Beijing’s ability to take advantage of arbitrage enhances its influence over the LNG market, but it also positions the country within a global shift. Players are increasingly intervening in the LNG market via opportunistic spot purchases. Although the PRC’s LNG portfolios consist primarily of long-term contracts, there has been an increase of spot market activity among LNG buyers, with Sinopec becoming a major LNG spot trader in the Asia-Pacific region (Baijiahao/Chaoji Shihua, November 6, 2024).

The PRC also has been increasing its LNG re-exports. Between January and October 2023, Chinese companies re-exported 14 LNG cargoes, up from eight in the same period in 2022 (ICIS, November 26, 2023). In 2025, re-exports surged to nearly 770 percent from 2024, which PRC analysts attributed to weak domestic demand and an anticipated U.S.-PRC tariff war (Baijiahao/Sanlang Macro, April 29). Some energy experts believe that the PRC is emerging as an LNG reseller in part because the country’s demand is decreasing and all of its supply is contracted up until 2035 (The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, September 1). New U.S. LNG contracts, such as a 15-year deal between ConocoPhillips and Guangdong Pearl River Management Group (珠江投管), further confirm this strategy (Sohu, June 6). U.S. contracts are known for their flexible destination clauses, and shorter-term agreements also indicate a desire for flexibility. The PRC might be limiting near-term U.S. LNG intake, but it is also locking in future supply, likely seeing long-term access as insurance against future volatility.

This suggests that the PRC uses LNG procurement to balance its energy needs while signaling it can currently meet this demand without U.S. LNG. Its decision to purchase U.S. sanctioned LNG from Russia similarly sends a message that the PRC’s purchasing decisions will not be influenced by U.S. actions (Reuters, September 15). Whatever the PRC’s LNG ambitions may be, its robust infrastructure and diverse LNG portfolio coupled with its complex energy mix places it in an advantageous position. It can meet its energy demands while also capitalizing on LNG market opportunities.

Pipelines Partnerships Strengthen Eurasia Ties

International cooperation is an important facet of Beijing’s energy diplomacy. As of 2022, the PRC had energy cooperation agreements with over 90 countries and 30 international organizations and regional platforms across Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe (People’s Daily, January 7, 2022). Through these agreements, the PRC aims to shape international energy governance and extend geopolitical influence. Strategic partnerships also form part of Beijing’s approach. This is part of its “Four Revolutions and One Cooperation” (四个革命、一个合作) approach, a new energy security strategy that promotes revolutions in energy consumption, supply, technology, and systems, alongside strengthening international cooperation (People’s Daily, April 9). Partnerships help fill the country’s domestic supply shortfall, provide diversification as a hedge against geopolitical disruptions, and enable the PRC to invest in overseas infrastructure that can absorb future demand surges or unexpected discoveries of additional natural gas deposits.

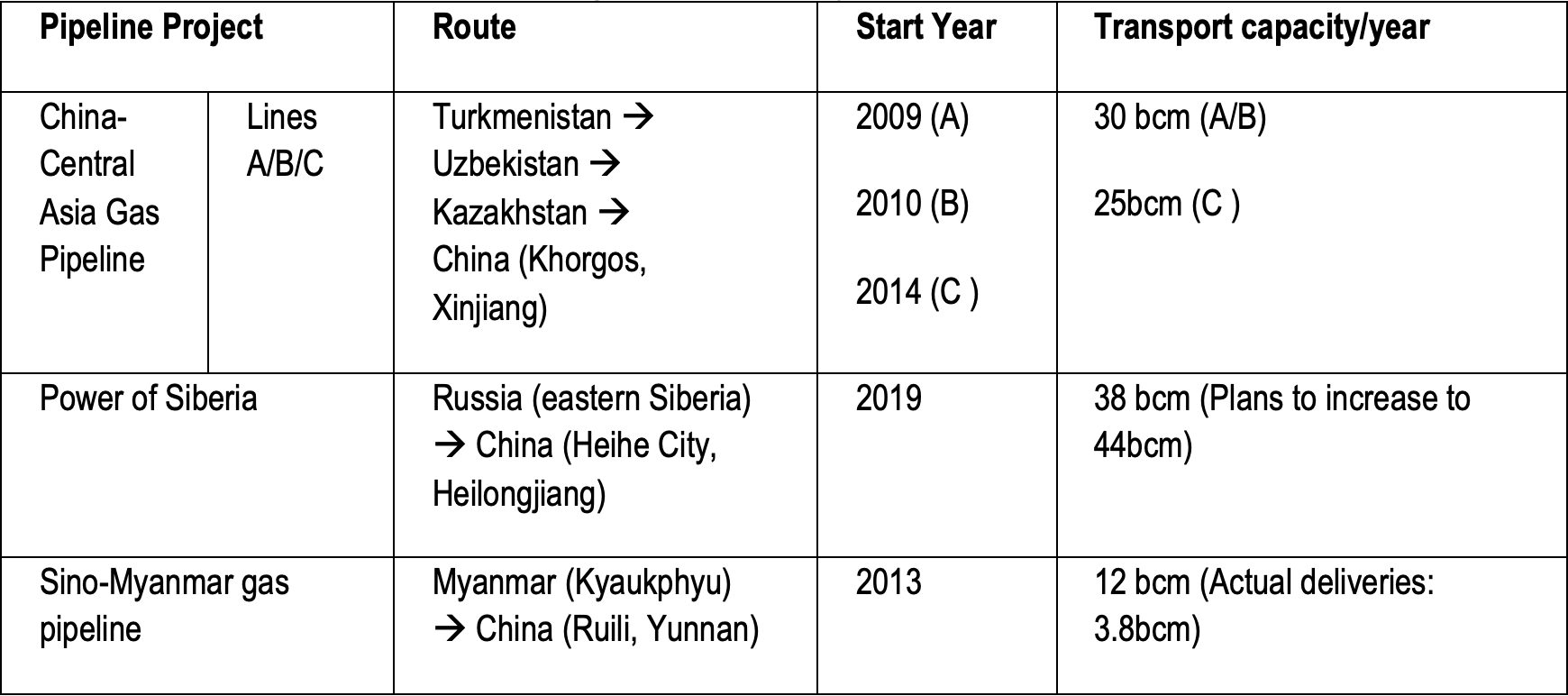

Energy infrastructure are central to this strategy. Pipelines tie the PRC more closely to its neighbors, while LNG’s maritime flexibility creates a different kind of geopolitical leverage. In 2024, the PRC imported 71 bcm of natural gas via pipeline from five countries: Turkmenistan (estimated 46 percent), Russia (estimated 40 percent), Kazakhstan (estimated 7 percent), Uzbekistan (estimated 4 percent), and Myanmar (estimated 3 percent) (Baijiahao/Logistics Revelation, February 2). These imports arrived via three pipeline projects: the China-Central Asia Gas Pipelines A, B, and C, the Power of Siberia pipeline, and the Sino-Myanmar gas pipeline (Petroleum Knowledge, December 1, 2024). Details of these projects are outlined in table 2 below.

Beijing views Turkmenistan as one of its “strategic energy partners” (能源战略伙伴) due to its prominent role as a supplier of pipeline gas to the PRC (Ministry of Foreign Affairs [MFA], January 6, 2023). Importing pipeline gas via Central Asia mitigates the risks entailed by maritime LNG imports. Shipments could be disrupted in any conflict scenario. Beijing has positioned its energy relationship with Turkmenistan as part of its One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative. The China-Central Asia Gas Pipeline often features in OBOR propaganda (Xinhua, August 18, 2023). The country’s rise as a destination for Central Asian resources also boosts the PRC’s economic and political influence in a region traditionally dominated by Russia, while it hopes to leverage deepening cross-border infrastructure to promote regional stability. At a recent meeting with Turkmen President Serdar Berdimuhamedow, President Xi called for the two countries to scale up natural gas cooperation and further increase OBOR cooperation (MFA, June 17). Speaking at the second China – Central Asia summit in June, Xi called for the acceleration of the construction of pipeline D (People’s Daily, June 18). According to agreements signed in 2013 and 2014, the pipeline will run through Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan and has an expected capacity of 30 bcm per year (CNPC, 2014). While progress on the pipeline has stalled, the completion of the Chinese West-East Gas Pipeline 4 this year – which ends in Kuqa, Xinjiang, the planned terminus of pipeline D – suggests the project may receive renewed attention (Yicai, September 29, 2024; GEM Wiki, accessed October 29)

The PRC’s other key pipeline gas partner, Russia, needs to urgently shift its gas exports to Asia to mitigate the decline in European demand following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Alongside the existing Power of Siberia project, the China-Russia Far Eastern route is under construction and expected to be operational in 2027 (Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, March 1, 2022). During the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in early September, Russia and the PRC reportedly agreed to increase Power of Siberia gas deliveries from 38 to 44 bcm per year and Far Eastern gas deliveries from 10 to 12 bcm per year (Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, September 1).

As with Turkmenistan, PRC pipeline projects with Russia appear to have stalled. A second Power of Siberia pipeline has been mooted by both sides for a number of years. This would allow Russia to transport up to 50 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually to the PRC via Mongolia for 30 years. Alexey Miller, CEO of Gazprom, announced that Russia and the PRC have signed a memorandum of understanding on the construction of the pipeline. But Beijing has been silent on the matter. The PRC’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Guo Jiakun (郭嘉昆) refused to provide any specific details on the project at a press conference in September (The Paper, September 2). Further details of the project are yet to be released. Pricing is expected to be a key sticking point (Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, September 1). For now, Moscow appears more eager to see progress as it attempts to secure new non-European buyers for its gas. While the announcement reaffirms support of Moscow through strengthening bilateral energy cooperation, Beijing’s priority is maintaining a flexible and diversified gas supply chain to avoid over-reliance on any single supplier.

Table 2: The PRC’s gas pipeline projects and respective routes.

Conclusion

Pipelines play an important role in the PRC’s pragmatic approach to gas policy. They mitigate its exposure to LNG market fluctuations and maritime chokepoints and likely give Beijing an advantage in pricing negotiations, strengthening its role as an LNG reseller.

The PRC’s recent suspension of U.S. LNG imports demonstrates that it is increasingly weaponizing its leverage over resources. Its moves to expand domestic capacity to receive and store LNG shipments while strengthening international energy cooperation with specific partners through pipeline deals also indicates geopolitical—not just economic—motivations. By limiting domestic supply issues and maintaining competitive pricing, Beijing’s approach to natural gas gives it room for maneuver in trade conflict with the United States, allows it to strengthen regional partnerships, and influence global energy systems.

The views expressed here are the authors’ alone and do not represent DSET or the Taiwanese government.