Briefs

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 19 Issue: 10

By:

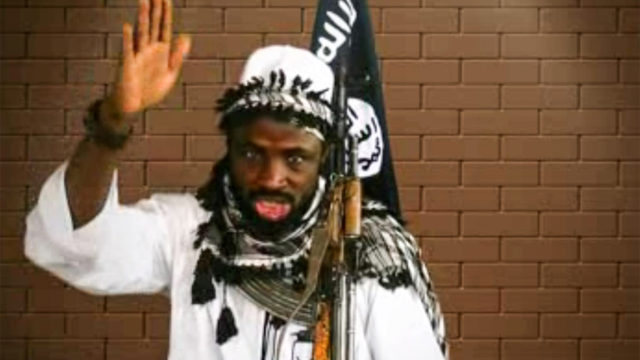

Killing of Boko Haram Leader Abubakar Shekau Boosts Islamic State in Nigeria

Jacob Zenn

On May 21, reports emerged from Nigeria, and especially from Boko Haram insider journalist Ahmed Salkida’s publication HumAngle, that longtime Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau was dead (HumAngle.ng, May 22). Shekau earned a reputation since assuming Boko Haram leadership in 2010 for being declared deceased by Nigeria’s army only to resurface in videos, alive, taunting the military (Militant Leadership Monitor, May 3, 2014). This time is different, however, because the army is not claiming to be responsible for killing Shekau. Rather, Shekau’s rivals in Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) launched an offensive into Shekau’s Sambisa, Borno state base. ISWAP killed some of Shekau’s guards, and held some sort of dialogue with the Boko Haram leader about surrendering and pledging loyalty to Islamic State (IS). However, Shekau apparently detonated his suicide vest, killing himself and at least one other ISWAP commander (HumAngle.ng, May 20).

Although ISWAP is yet to comment on Shekau’s death or provide evidence of it, the death does seem to be confirmed. Several days before Shekau’s death, for example, Abu Musab al-Barnawi, the ISWAP leader who dethroned Shekau from leadership in August 2016 and was himself replaced in March 2019, released an audio announcing that IS reinstated him to be the “caretaker” leader of ISWAP (Ra’id Media Agency, May 16). Al-Barnawi’s father, Muhammed Yusuf, had led Boko Haram until his death in 2009 at the hands of Nigerian security forces and his then deputy, Shekau, assumed leadership (Daily Trust, July 4, 2010). However, over the next several years Shekau became excessively ruthless toward Muslim civilians and sub-commanders. As a result, al-Barnawi appealed successfully to IS for Shekau’s removal in August 2016. The reinstatement of al-Barnawi to ISWAP leadership just before the offensive against Shekau indicates that al-Barnawi’s promotion and Shekau’s demise were related and both IS and ISWAP sought to put an end to the Boko Haram leader, whose brutalities and disrespect of IS’ orders made him anathema to the organization and its province in the area (Al-Naba, August 2, 2016).

Shekau, for his part, gave a final sermon on the day before his death that has been leaked publicly (Twitter.com/@HumAngle, May 22). He indicated that many of his fighters had been killed and the group was facing calamities. Shekau said he would never be loyal to anybody. His tone also suggested he knew was near the end. However, the dramatic fashion in which he reportedly ended his life evidently took ISWAP by surprise and, for the first time in several years, Nigeria will enter a post-Shekau era. This is not necessarily auspicious from a counter-insurgency perspective because ISWAP is, after all, a more effective insurgent force in terms of tactics and engaging the population than Shekau’s faction.

Moreover, not only ISWAP, but also IS itself, will be bolstered with Shekau out of the picture. They considered him a “renegade” for not following IS orders and “dividing the mujahidin” (Telegram, February 14, 2020). In sum, Nigerians have a reason to celebrate the demise of Shekau, who had brutalized so many civilians, but little reason to expect a waning of the insurgency overall as a result of his death. In addition, Shekau may have a successor, whose identity is uncertain, but who has appeared in a number of Shekau faction videos delivering sermons, including the claim of the Zabarmari massacre earlier this year in which dozens of Borno farmers were decapitated. “Shekauism” may, therefore, live on (Telegram, December 1, 2020).

***

Ethnic Militias Rise up to Oppose Myanmar Junta

Jacob Zenn

After the Myanmar military launched a coup in February to unseat the country’s democratically elected government, Myanmar has fallen into increasing disorder. New militias and insurgent movements are emerging throughout states on the country’s periphery where ethnic minorities predominate. Aung San Suu Kyi, who was arrested during the coup, will “soon appear for trial,” according to the Myanmar junta leader’s statement on a Chinese television interview (Twitter.com/@TostevinM, May 22). The lack of any political reconciliation with her or handing power back over to any civilian authorities indicates reconciliation is unlikely anytime soon.

Meanwhile, signs are emerging that Myanmar’s military, known as the Tatmadaw, could be seeing dissent within its ranks. Army Major Hein Thaw Oo defected from the army and has begun training several dozen other defectors to fight the junta. According to Hein Thaw Oo, it was not necessarily the coup itself, but the junta’s killing of civilian protesters in the aftermath of the coup that caused his fighters and him to defect (Myanmar Now, May 9).

Ethnic militias are also rising up to oppose the junta. The Chinland Defense Force, located in Chin State bordering Bangladesh, killed six junta soldiers, including an army captain, in May (Irrawaddy.com, May 21). On the other side of the country civilians in Kayah State, in the east bordering Thailand, are being arrested by junta soldiers on suspicion of joining the Karenni Army and other civilian militias to oppose the junta (Irrawaddy.com, May 21). Even in the capital, Yangon, a junta official was shot dead in the street after five other officials had been assassinated in other cities throughout the country (Irrawaddy.com, May 18). Only days after the Yangon assassination, bombs were detonated in Yangon’s business district, killing two police officers (Irrawaddy.com, May 21).

In the far south of Myanmar, civilians have also engaged in peaceful methods of protest to oppose the junta. They have, for example, held mass motorcycle rallies as a means of protest in the southernmost Thanintharyi Division (Twitter.com/@Khaing_Hsuu, May 23). In the far north of the country, in Saigaing, civilians have held Buddhist prayers to “Save Myanmar” and pray for the lives of protesters (@sthk_u, May 23). Thus, at the same time that ethnic militias are newly rising up or continuing longstanding battles against Myanmar’s military and other anti-junta militants are engaging in ‘lone-attacker’ operations against the military, peaceful mass action is still being used to demonstrate opposition to the junta.

Little organizational command and control exist between the various elements opposing the military. Moreover, any potential unifying figure, like Aung San Suu Kyi, is unable to rally the opposition because she is in junta custody. Nevertheless, growing evidence from around the country indicates that the junta is losing control and the country risks spiraling into longer term instability. With the junta unwilling to compromise and powerful countries like China and Russia supporting the junta and providing it arms, it is also unlikely any ASEAN or Western pressure will lead to the military stepping down (Irrawaddy.com, May 21). More violence and mass civilian actions against the junta, therefore, appear inevitable.