Cairo’s Struggle to Contain North Sinai Militancy

Cairo’s Struggle to Contain North Sinai Militancy

On July 18, militants executed four individuals in the town of Bir al-Abd, in North Sinai, for alleged cooperation with the Egyptian security services. One day later, at least two people, including a civilian and a member of the security services, were killed in an attack on a security checkpoint in Sheikh Zuwaid, near the border of the Gaza Strip and Egypt (The Algermeiner, July 18). Islamic State (IS) claimed responsibility for both attacks, which were carried out by its local affiliate, Wilayat Sinai, formerly known as Ansar Jerusalem (AJ). These incidents followed a similar spate of violence one month earlier. On June 4, militants killed eight Egyptian security personnel in an attack on a security checkpoint west of al-Arish, the capital of the North Sinai governorate, timed to coincide with the holiday of Eid, marking the end of Ramadan (The National, June 5). IS subsequently claimed responsibility for this assault. Local reports the following week said that militants had kidnapped at least fourteen civilians on the highway leading to al-Arish (Middle East Eye, June 14). Later that month, militants also killed seven police officers near the same city (Al-Arabiya, June 26).

The rapid succession of attacks in this period were most likely a response to IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s call in April for intensified operations. IS’ mainland Egypt affiliate has weaker capabilities than Wilayat Sinai has in North Sinai, and so the group will have focused these renewed efforts on their namesake region.

Increased Insurgency and Operation Sinai

Insurgency in North Sinai has increased significantly since 2013, with militants looking to exploit that instability that followed the military coup that ousted former President Mohamed Morsi. In November 2017, militants killed around 300 individuals in an attack on a Sufi mosque in Bir al-Abed, North Sinai—the deadliest ever attack in Egypt (Haaretz, November 25, 2017). IS did not issue a claim of responsibility, although its local affiliate was credibly behind the attack. Local reports suggested the group had warned civilians ahead of the attack not to attend the mosque, which is frequented by members of the security services. Militants also reportedly brandished IS’ black flag during the assault (Ahram, November 25, 2017).

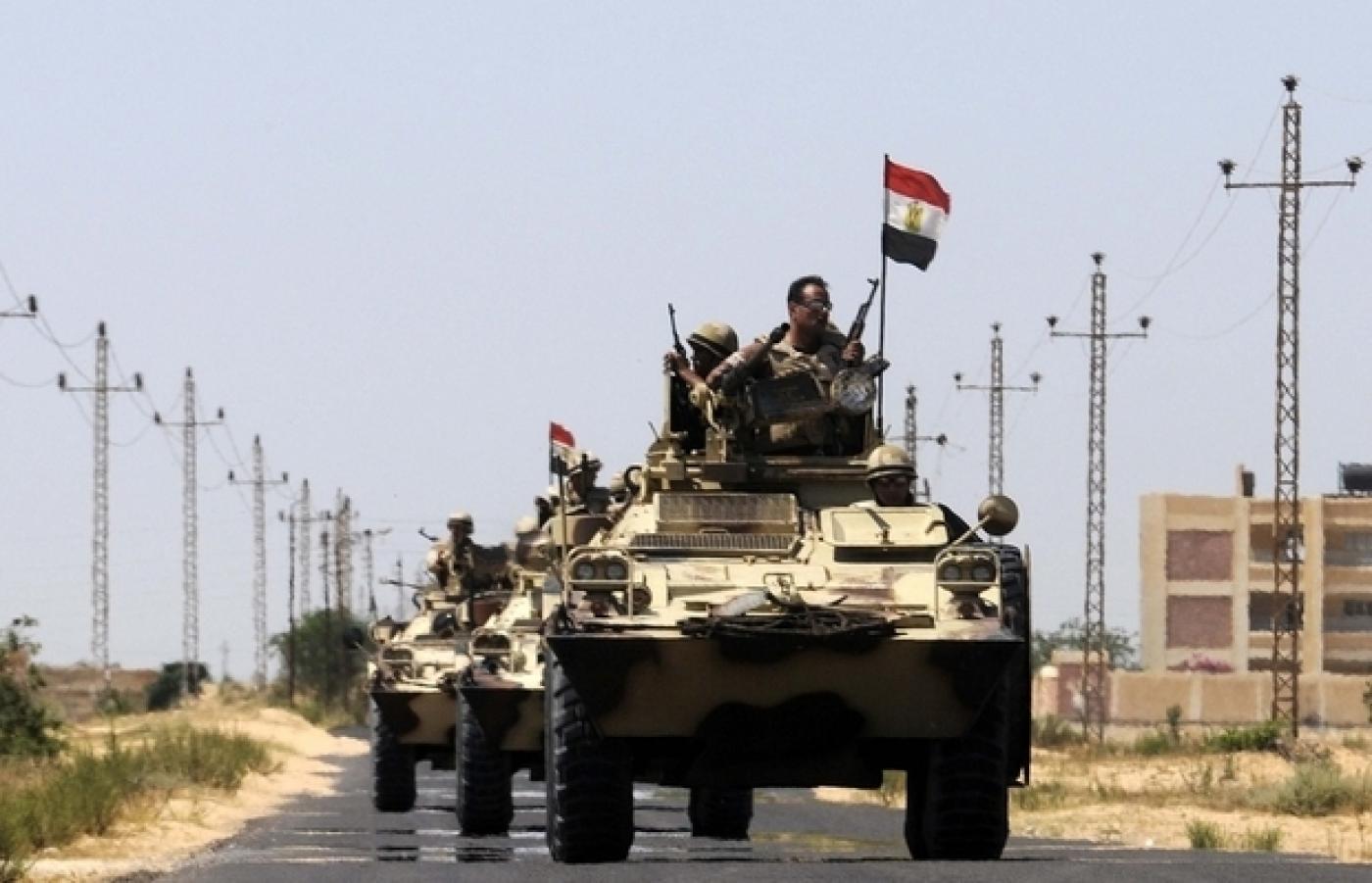

In response to this insurgency, Cairo launched Comprehensive Operation Sinai in February 2018, shortly before the Egyptian presidential election in March. Wilayat Sinai carried out a number of retaliatory attacks—including an assault on the Gouda 3 checkpoint near al-Arish airport in February that killed and injured fifteen Egyptian soldiers—to show that the major military operation had not damaged its capabilities and to maintain its credibility (Mada, February 21). Meanwhile, the military’s aggressive counter-insurgency tactics heightened local resentment toward Cairo. Operation Sinai, for instance, involved the displacement of thousands of civilians living in the region and contributed to longstanding tensions between local tribes and security services. Wilayat Sinai has in turn been able to capitalize on such tensions to increase support for its insurgency.

Challenge to al-Sisi’s Presidency

Wilayat Sinai intends for its insurgency to undermine confidence in the security services and, in turn, embarrass and destabilize the central government. The group also hopes to damage the tourism industry, Egypt’s main source of foreign revenue, by sustaining its campaign of violence. The effectiveness of this strategy was demonstrated when militants downed a Russian passenger aircraft leaving Sharm el-Sheik in October 2015, killing 224 people. The incident contributed to both a significant drop in visitor numbers and foreign currency shortages.

There is evidence to suggest the government is taking steps to limit instability in the region, in addition to its ongoing security crackdown on militants. Cairo has, for instance, launched a number of development initiatives in the Sinai peninsula, while coming up with plans for free trade zones in al-Arish, Rafah, and Nuweib, which it hopes will stimulate job creation. Last month, the planning ministry announced infrastructure and development funding of $316 billion, or (EGP 5.23 billion) for the Sinai covering the 2019-2020 fiscal year—a 75 percent increase in funding from the last financial year (Al-Monitor, September 1). This will help provide opportunities for the local population, making it harder for Wilayat Sinai to exploit credible socio-economic grievances among Sinai residents. It will, however, take several years for Sinai residents to feel the benefits of such funding, and the ongoing fighting between the Egyptian military and insurgents will delay the construction and implementation of planned projects.

Containing militancy in North Sinai will, therefore, remain a major long-term challenge for President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, with recent changes to the Egyptian constitution meaning that he is set to remain in power until 2034. Any inability on al-Sisi’s part to prevent major attacks in the Sinai would damage his security credentials, and increase the risk of rivals emerging to challenge his positon, particularly from within the military establishment. Wilayat Sinai will aspire to attack high-profile targets, such as places of worship, airports, and infrastructure—including a new gas pipeline between Israel and Egypt expected to be fully operational in November. Militants’ limited capabilities and ongoing security operations will, however, foil the majority of significant plots, and as such the primary targets of attacks will remain security personnel and other government interests.