China in Greenland: Mines, Science, and Nods to Independence

China in Greenland: Mines, Science, and Nods to Independence

Editor’s Note: Miguel Martin has previously published on Arctic affairs under the name Jichang Lulu.

Although China’s recent Arctic white paper (SCIO, January 2017), a document primarily intended for foreign consumption, avoids direct mention of Greenland, the island plays an important role in the PRC’s Arctic strategy, due to its abundant natural resources, importance as a scientific research base, and possible emergence as an independent state that could give China more influence in Arctic affairs. Little actual Chinese investment has taken place in Greenland to date, but Chinese companies are expected to be involved in two of the island’s largest planned mining projects (including one of the world’s largest rare-earth mines), while plans to build research facilities have also been announced, among them a year-round research base and a satellite ground station. Meanwhile, while Chinese diplomats have avoided any actions that could be construed as support for immediate Greenlandic independence, the possibility is now openly discussed among Chinese academics specializing in the Arctic.

The Long Road to Independence

Greenland enjoys a high level of autonomy as a constituent country of the Danish Kingdom. Most of Greenland’s political class is committed to leaving the Kingdom, although economic independence remains unfeasible in the medium term. Denmark’s annual block grant provides for more than half of Greenland’s state budget. Seafood accounts for more than 94% of exports, creating vulnerability to price variations (Grønlands Statistik, 2017). The country lacks a qualified workforce. Roughly half the population has only completed lower secondary education (Grønlands Økonomiske Råd, August 2017).

The government sees developing transportation infrastructure as a way of expanding other industries, in particular tourism (Naalakkersuisut, December 2015). Possible Chinese involvement in infrastructure development has been under discussion for years. In 2015, then-minister Vittus Qujaukitsoq talked about airport, port, hydroelectric and mining infrastructure development to representatives of companies including Sinohydro (中国水电), China State Construction Engineering (CSCEC, 中建) and China Harbour Engineering (CHEC, 中国港湾) (MOFCOM, October 2015). Infrastructure projects were also discussed during the premier’s November 2017 visit to China (Naalakkersuisut, Huanqiu, November 2017), although no Chinese company is known to have shown interest so far. At least some of the infrastructure plans advocated by the local government will not be profitable (Danmarks Nationalbank, Grønlands Økonomiske Råd, August 2017), requiring long-term state support. It remains less than clear whether the Greenlandic state will be able to maintain such funding. The plans are controversial in Greenland, and have generated friction with Denmark (Folketinget, January 2018). The uncertainty and lack of clarity surrounding these projects seems to be keeping Chinese companies away.

Given the generally favorable attitudes toward China in the Greenlandic government, however, its independence could be geopolitically advantageous to the PRC. China has consistently avoided showing any form of support for such ambitions, and has taken care to treat Greenland as a sub-national entity, but despite this caution, the issue of independence is now openly discussed in Chinese academia. An article published last year with Guo Peiqing (郭培清), a leading polar politics scholar, as lead author, states that “the Danish government recognizes the objective inevitability of Greenland’s independence”. The piece notes that Greenland cannot cope on its own with the challenges it faces, so that “getting help from outside forces will be an unavoidable option”, making Greenland’s development “both an internal affair of Greenland and the responsibility and duty of the international community”. [1] Coming from Guo, who has argued for the strategic importance of Arctic resources (Quanzhou wanbao, December 2014), this can be read as a call for China to become involved, couched in the palatably ‘internationalist’ language of polar affairs.

Mining for Cooperation

Greenland has abundant mineral reserves, but low commodity prices and high development costs have hindered development. Only one mine is currently active, and another one is expected to come online in summer of 2018. Four sites in Greenland have attracted serious interest from Chinese companies; two have a realistic chance of coming online in the short term. Once in operation, they would make Chinese SOEs the top foreign investors in Greenland’s natural resources.

The most important mining project in Greenland is also the most controversial: the uranium and rare-earth site at Kuannersuisut (Kvanefjeld), one of the world’s largest rare-earth deposits. The license owner, ASX-listed Greenland Minerals and Energy (GME), had signed non-binding agreements with China Nonferrous to develop the mine, but in 2016 rare-earths processor Shenghe Resources (盛和资源) bought an eighth of GME and stated its interest in increasing its stake to a controlling one once the project enters production (Shenghe, September 2016; Sermitsiaq, Jichang Lulu, June 2017). Although listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, Shenghe is ultimately controlled by the PRC Ministry of Land and Resources (MLR), through the Chengdu Institute of Multipurpose Utilization of Mineral Resources (IMUMR, 中国地调局成都综合所), its controlling shareholder (Shenghe, IMUMR). Shenghe’s chairman is also the director of the IMUMR (Shenghe, IMUMR).

Shenghe’s investment, one of a number of rare-earth investments globally, including at the Mountain Pass mine in the United States, is consistent with PRC government calls for the rare-earth industry to build up strategic reserves (NDRC), and its encouraging companies to “develop mining resources abroad” (MIIT, October 2016). The IMUMR has referred to the acquisition of the stake in Kvanefjeld as “implementing the vision on mining cooperation” reached between its minister and Greenland officials (IMUMR, December 2016), and cited the Greenland investment in talks on plans to acquire rare-earth resources abroad in the context of the China Geological Survey’s implementation of the 13th Five-Year Plan (IMUMR, December 2016). The Kvanefjeld project is controversial in Greenland, as many (including the current minister responsible for natural resources) oppose uranium mining (KNR, November 2016). The project has not yet obtained an exploitation license.

The mining project with PRC involvement closest to production is the world’s northernmost: the Citronen Fjord iron and zinc mine at 83 degrees north latitude. Ironbark, its Australian owner, intends to work with state-owned China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group (中国有色矿业集团) to finance and build the project, initially using foreign (likely Chinese) labor, then gradually transitioning to local workers (Naalakkersuisut, September 2016). The project has a production permit (Naalakkersuisut, December 2016), but is having trouble finding investors (Sermitsiaq, September 2017), although China Nonferrous remains interested, and sent a deputy general manager to visit the site last August (mining.com, August 2017; Jichang Lulu, October 2017).

Dual-use Research

As in Antarctica, mineral prospecting is the main goal of China’s scientific activities in the Arctic; many of Greenland’s major mineral sites have been visited and studied by Chinese scientists. The Chinese Geological Survey (CGS, 中国地质调查局), under the MLR, has played an active role in researching and promoting mineral sites of potential interest to China. In 2011, the CGS started a two-year research project to identify the mineral resource potential of deposits in Canada and Greenland (CGS, June 2014). At the height of interest in Greenland mining projects, multiple sites were described in Chinese-language scientific publications. For example, a 2013 issue of Geological Science and Technology Information (地质科技情报) carried eight articles on Greenland mining, totaling 58 pages. In 2012, a CGS publication advocated exploring and developing mineral resources in Greenland “as soon as possible”, contrasting nascent China-Greenland exchanges with well-developed Western interest in Greenland’s resources and strategic location. [2] The MLR actively promotes its research findings to the mining industry, and both the MLR and (to a lesser extent) provincial-level organs have a central role in identifying and promoting projects of interest. [3]

Plans for a permanent research station in Greenland were discussed as a priority by Chinese polar program leaders in 2015 (China Arctic and Antarctic Administration (CAA), January 2016). In May 2016, the State Oceanic Administration (SOA, 国家海洋局) signed an agreement with a Greenlandic ministry that included the construction of a station (SOA, China Ocean News (中国海洋报), May 2016). Two possible locations have been hinted at (Twitter, Sermitsiaq, Jichang Lulu, October 2017): one seemingly near Kangaamiut or Maniitsoq in the island’s southwest, and another near the Citronen Fjord zinc project of interest to China Nonferrous. Its location could provide a unique vantage point, being farther north than Denmark’s Station Nord and the US Thule Air Base (Pituffik).

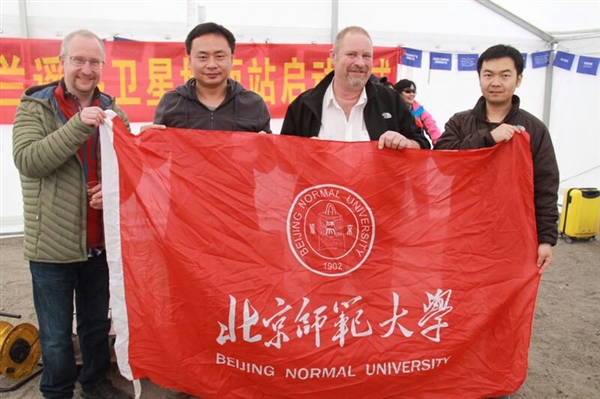

Last May, a ceremony was held in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland’s airport hub, to launch a process intended to lead to the establishment of a satellite ground station to be used for climate change research, which could also be used for the dual-use Beidou navigational system. The ceremony was led by Professor Cheng Xiao of Beijing Normal University, a leading polar scientist, specializing in remote sensing, and featured Zhao Yaosheng, a Beidou pioneer with a military background. They traveled to Greenland as part of a contingent of 100 ‘elite’ tourists, including Rear Admiral Chen Yan (陈俨), former political commissar of the South China Sea fleet, who served as an audience for the ceremony (sciencenet.com, June 2017; AG, November 2017; Jichang Lulu, December 2017). The ground station project was reported on Chinese media (sciencenet, June 2017), but was not known to Greenland’s authorities, whose authorization would be required, until it was reported on by the author and local media (Jichang Lulu, October 2017; AG, November 2017). It’s unclear if and when construction will start.

Conclusion

The Greenlandic government is enthusiastic about China as a key investor in mining and infrastructure projects, as well as a source of tourism and a customer for seafood, with a foreseeable central role in reducing economic dependence from Denmark. Such enthusiasm has not been reciprocated through major investments, although that might be about to change. Chinese companies remain cautious, as the development of the mining industry is hindered by high costs, low commodity prices, a lack of infrastructure and financial uncertainty. In political contacts, China avoids any signs of support for Greenland’s independence, but the topic is now open for academic discussion. Although it remains unstated, an independent Greenland with China as a key trade and investment partner and good political relations would be a valuable geopolitical asset in the context of China’s long-term Arctic strategy.

Miguel Martin, who frequently writes under the penname Jichang Lulu, is an independent researcher with an interest in China’s activities in the Arctic and focus on Greenland. Martin’s blog has frequently been the first Western-language outlet to report on news related to China’s interests in Greenland. Follow him on Twitter at @ jichanglulu.

Notes

[1] See Contemporary International Relations (现代国际关系), August 2017. [2] See Geological Work Strategic Research Reference (地质工作战略研究参考) 99, Oct 2012. [3] For example, information on Greenland was included in materials offered by the CGS at a MLR-organized forum on overseas mineral exploration in Beijing, attended by government departments, mining companies, banks and academics (CGS, Overseas Mining Exploration and Development Newsletter (境外矿产资源勘查开发简讯), 50, Oct 2013).