China Makes a Move in the Middle East: How Far Will Sino-Arab Strategic Rapprochement Go?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 22 Issue: 24

By:

Introduction

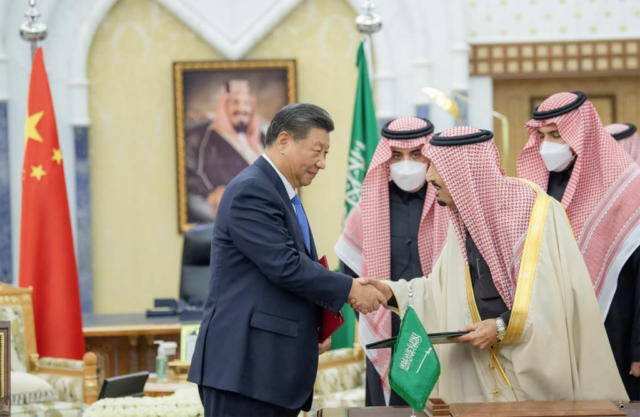

With a well-planned strategy and a careful exploitation of the gaps opened by U.S. foreign policy shifts, China has successfully increased its role as a strategic actor in the Middle East, including by gaining a foothold in the regional arms market. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s early December visit to Saudi Arabia, upon King Salman’s invitation, exemplifies the recent improvement in Sino-Arab ties (Xinhua, December 8). While in Saudi Arabia, Xi initiated two new multilateral forums intended to strengthen engagement between China and the Arab world: the China-Arab States Summit and the China-Gulf Cooperation Council summit (Xinhua, December 11).

In addition to deepening political rapprochement between Beijing and several regional countries, China is simultaneously establishing crucial military-strategic ties with key Middle Eastern states. Chinese-made drones are already present in the arsenals of multiple Arab countries and technological cooperation between Beijing and its regional counterparts is rapidly increasing. The most striking example in this regard was the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) revocation of the F-35 deal that constrained its cooperation with the Chinese tech and telecommunications giant Huawei over 5G technology (Al Arabiya News, December 14, 2021). As many Arab countries’ doubts about Washington’s commitment to regional security grow, more and more countries are increasingly open to entreaties from China.

Although Beijing is known for using infrastructure investment and economic leverage to increase its overseas influence, Sino-Arab relations are not as purely transactional as some argue. On the contrary, they carry the utmost strategic value. With important partnerships in the fields of technology and arms transfers, Chinese influence in the region is already more extensive than many realize. As China improves its relations with once-close U.S. allies, Washington faces two imminent risks. The first risk is economic, whereas the second danger is strategic. The economic risk is that Washington is already losing its most lucrative arms market to its biggest rival. The second risk relates to geopolitics and has strategic implications. While filling the burgeoning arms market with alternatives to Western suppliers, China is also expanding strategic ties with the leading Arab states, which could reset the balance of power across the region.

Beijing and Riyadh: An Alignment Years in the Making

Although bilateral ties have taken off of late, Sino-Saudi cooperation is hardly new. The two countries officially established diplomatic relations in 1990 (Xinhuanet, February 9, 2009). In fact, official relations were already preceded by defense cooperation in the 1980s, including the sale of Dongfeng-3 (DF-3) medium-range ballistic missiles (South China Morning Post, December 8). However, the number of arms deals increased after 2014, as U.S.-Saudi relations soured, following the OPEC+ oil crisis and the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. China drafted its Arab Policy Paper in January 2016, which aimed to boost the dialogue and cooperation between Beijing and Middle Eastern countries (Xinhua, January 14, 2016). Shortly after, Saudi Arabia and China announced a five-year plan for an enhanced security agreement. Supported by 17 different high-level agreements, the plan included partnerships on science and technology, as well as counterterrorism cooperation and joint military drills (PRC State Council, August 30, 2016). The first joint bilateral counterterrorism drill took place in October 2016, and the coming years followed suit with various exercises, such as the Blue Sword naval training in 2019 (China Military Online, November 20, 2019).

As noted, President Xi recently made headlines for his three-day visit to the Saudi capital from December 7-10. During the trip, Xi attended the China-Arab States Summit and the China-GCC Summit in Riyadh, both of which were held for the first time. According to the statements made by the Saudi investment minister, the two countries signed over 30 bilateral trade and investment agreements worth around $50 billion during the three-day visit (Al Arabiya News, December 8). The promised areas of strategic cooperation include oil, green energy, military, logistics and cloud computing (Masrawy, December 12). The deals are financially significant as Saudi Arabia is China’s biggest trade partner in the Middle East (Asharq Al-Awsat, October 21, 2021). Moreover, Saudi Arabia is an active participant in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which yields

favorable investment and other economic partnership opportunities, while opening the way to future cooperation. Both sides frame the relationship as mutually beneficial (Global Times, December 9). With several annual supply deals with state oil refiners, China benefits from a secure oil supply, while Saudi Arabia enjoys a generous flow of combat-proven weapon systems and support for its strategic projects.

U.S. policy choices are an important factor fueling the rapprochement between the two countries. The Biden administration is currently trying to turn back the arms sales Trump approved for the Middle East. This change in policy was reflected in the temporary freeze of the sale of F-35 fifth-generation fighter jets to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), as well as the suspension of munition sales to Saudi Arabia. During the state visits that took place as part of the planned program, King al-Salman noted that the Chinese-Saudi partnership “effectively promoted regional peace, stability, prosperity and development”, emphasizing the positive trajectory of the bilateral relations (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China [FMPRC], December 7).

Over the past few years, Saudi Arabia has scaled up its arms procurement from China. Rumors circulated on social media after the Zhuhai Air Show in November arguing that Riyadh purchased $4 billion worth of military equipment and weapons from Beijing, marking a significant increase compared to the previous arms deal (Zhihu, November 12). In addition to these public-private partnerships, the military-strategic side of Sino-Saudi relations, particularly the Chinese fingerprint on Riyadh’s ballistic missile program, is especially significant for U.S. foreign policy.

The Real Deal: Chinese Signature on Saudi Arabia’s Upcoming Ballistic Missile Program

As noted, Chinese sales of ballistic missiles to Saudi Arabia are not new, but go back over three decades to 1987, when a deal was signed for the 3000-kilometer range Dongfeng-3 (DF-3) missiles. In 2007, Saudi Arabia opted for other Chinese solutions to expand its ballistic missile arsenal. The DF-2 missiles are one prominent example. Riyadh showcased Chinese missiles in a national military parade, which many analysts regarded as a political message to the U.S.

Known for its desire to build its own indigenous missile program, Saudi Arabia has hitherto largely lacked the means to kickstart such an initiative. Its familiarity with Chinese ballistic missile technologies and established links with Beijing put China in the higher ranks in the eyes of the Saudis as a reliable partner. The Chinese and the Saudis share a history of cooperation, including missile technology transfer. Although he did not touch on the allegations, a People’s Republic of China (PRC) Foreign Ministry spokesperson recently stated that the countries are strategic partners with cooperation in several fields, including trade and defense (FMPRC, December 9). Consequently, the PRC appears to be the most viable partner for Saudi Arabia as it works to develop its ballistic missile program.

In late 2021, U.S. Senator Ed Markey attracted considerable attention when he said that Saudi Arabia started to manufacture its own ballistic missiles (Senator Ed Markey Twitter, December 23, 2021). Private satellite imagery taken between October 26 – November 9, 2021 confirms this claim. The images show a production site located in the town of Dawadmi, which is located 200 kilometers from Riyadh. The photos feature a solid propellant production area and an engine test stand (Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, January 13). Given the past partnerships, the increasing sense of trust, a generous technology transfer and previous familiarity with Chinese missile technologies, Beijing appears the probable partner for Riyadh in this ambitious project.

(Image: Solid Fuel Disposal Site, Al Dawadni Solid Fuel Production and Test Site, source: MIIS)

However, Riyadh’s development of an indigenous ballistic missile program poses a number of risks that threaten to further destabilize the region by intensifying the security dilemma between Saudi Arabia and Iran, which could fuel an uncontrolled arms race in the region. As its relations with Riyadh deepen, Beijing will increasingly struggle to maintain balance in its Middle East strategy. Such a project designed under Chinese influence will have implications for regional threat perceptions. on Second, it allows China to deepen its strategic-military footprint in the region, by establishing itself as a credible and reliable alternative to the West. Third, it shortens the Saudi pathway to a potential nuclear strike capability, should they acquire nuclear warheads, as several Chinese ballistic missiles are dual-use capable of carrying nuclear payloads.

Conclusion

These developments are rooted to a significant extent in U.S. policy, in particular inattention to the continued high threat perception of Saudi Arabia and other Arab allies toward Iran. The primary driver behind Saudi Arabia’s desire to boost its defensive and offensive capabilities is the Iranian threat. Therefore, Washington’s perceived limitations in being able to counter Tehran’s aggressive behavior towards its regional allies carry costs in the Middle East. Left out in the cold after repeated requests to purchase U.S.-made ballistic missiles (and previously UAVs) Riyadh has started seeking alternatives to counter Iran’s growing power and influence.

At present and in the near future, Washington will have a hard time trying to counter China in the Middle East, but should rather to seek to rebuild relationships and regain trust with its once-close regional allies. Avoiding future arms freezes and improving dialogue are the first steps in this regard. Another important aspect is persuading Riyadh that working with China can work against its favor in the long-run, especially given the rather close relations between China and Iran. Although it might be too late to turn back time and reverse the economic partnerships between Beijing and Riyadh, as manifested in BRI, there is still time to make things right and avoid the emerging Chinese – Saudi strategic partnership being set in stone.

Sine Ozkarasahin is an analyst at EDAM’s defense research program. She holds a BA from Leiden University in International Studies (with a specialization in North American Studies) and a postgraduate degree in International Development (with specializations in Middle Eastern Studies and Project Management) from Sciences Po Paris. Her work at EDAM focuses on open-source intelligence analysis, drone warfare, defense economics and emerging defense technologies.