China Moves Ahead on Digital Yuan Before 2022 Winter Olympics

China Moves Ahead on Digital Yuan Before 2022 Winter Olympics

Introduction

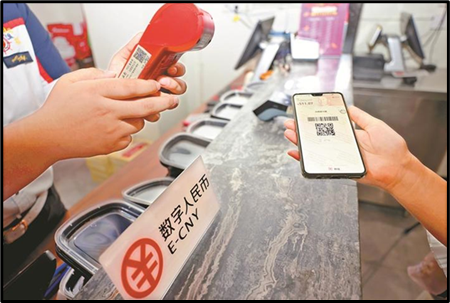

With the People’s Republic of China (PRC) a frontrunner in the global race towards digital currency, the central bank People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has taken several steps this year to explore the international use of a digital yuan (e-CNY). Although there is no official timetable for the launch of China’s sovereign digital currency, economic planners are reportedly aiming to implement the digital yuan ahead of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing—one year from now. Ahead of the Lunar New Year (February 12) this year, pilot programs trialing the nation’s digital currency, formally known as the Digital Currency / Electronic Payment system (DC/EP, 数字货币/电子支付体系, shuzi huobi/dianzi zhicun tixi), were rolled out in top cities such as Shenzhen, Suzhou, and Beijing. Shanghai and Guangdong have also announced plans to pilot the e-CNY (SCMP, February 8). A joint venture between the PBOC’s Digital Currency Research Institute (3 percent ownership) (DCRI, 中国人民银行数字货币研究所, zhongguo renmin yinhang shuzi huobi yanjiusuo), the PBOC China National Clearing Center (34 percent ownership), the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) (55 percent ownership), and several other Chinese entities was established on January 16 (money.163.com, February 6).

The timing of the creation of the new joint venture, called the Finance Gateway Information Services Company Limited (金融网关信息服务有限公司, jinrong wangguan xinxi fuwu youxian gongsi), raised eyebrows abroad, as the dollar-dominated SWIFT financial payment messaging system has in the past been used as a powerful tool by Washington to impose financial and economic sanctions against countries such as Russia, Iran or Pakistan. Concerns grew last year that the U.S. might move to exclude China or Hong Kong from SWIFT amid calls for economic decoupling and following a raft of sanctions targeting Chinese officials (Quartz, August 18, 2020; SCMP, August 25, 2020). China’s alternative to SWIFT, the Cross-border Interbank Payment and Clearing System (CIPS), will also own a 5 percent stake in Finance Gateway. (SCMP, February 4).

In another strong signal of China’s commitment to internationalizing the digital yuan, the PBOC announced on February 24 that it would be joining the Multiple Central Bank Digital Currency Bridge (m-CBDC Bridge) to study the feasibility of the use of digital currencies in cross-border transfers, international trade settlement, and foreign exchange transactions, among others (Xinhua, February 24). First established by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and the central bank of Thailand in 2019, the m-CBDC Bridge also includes the central bank of the United Arab Emirates and the Switzerland-based Bank for International Settlements (BIS), which is owned by 63 central banks across the world (SCMP, February 24).

China’s Interest in a Digital Yuan

Online nonbank payments—now dominated by technology powerhouses such as Tencent and Alibaba—developed in China during the early 2010s. The PBOC formed a group to research the development of a national digital currency in 2014. This later grew into the Digital Currency Research Institute (DCRI). In 2016, the PBOC revealed its plans to develop a digital currency in January and launched a prototype research and trading platform for digital currency in July (Jinse Finance, July 4, 2017). During the same year, the State Council included blockchain technology as a developmental priority in the 13th Five Year Plan (FYP) (2016-2020). The PBOC’s DC/EP project was organized and approved by the State Council in 2017 (China Banking News, October 2, 2018). Pilot programs between competing digital wallet operators (including both state-owned banks and e-commerce companies) testing the distribution of the e-CNY to consumers began in 2019 (China Briefing, February 8).

As of January 2, 2020, the PBOC had filed 84 published patent applications on concepts including: digital currency management, circulation and interbank settlement; digital currency wallets; processing payments and deposits and distributed ledgers (Chamber of Digital Commerce, February 2020). Implementing the digital yuan was prioritized in the 14th FYP (2021-2025) outline, released after the October Fifth Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) (People’s Daily, November 5, 2020). In November, the governor of the PBOC Yi Gang (易纲) announced that the value of pilot program digital yuan transactions had reached 2 billion RMB ($300 million), up 82 percent from numbers reported in August (163.com, November 8, 2020).

It is important to note here that the digital yuan is not structured in the same way as wholly decentralized and user-owned cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin. Nor is it equivalent to so-called “stablecoins” such as Facebook’s Libra (now Diem) that will be backed by a basket of fiat currencies (Coindesk, August 20, 2019; Diem, updated December 1, 2020). Instead, the DC/EP is a central bank digital currency (CBDC) that is aimed primarily at digitalizing the cash supply (and lowering the cost of issuing currency); strengthening the state’s ability to crack down on illegal financing while increasing the efficiency of payments and settlements and, in the long-run, creating the conditions for the implementation of irregular monetary policy (Xinhua, April 20, 2020). Details about the technological underpinnings of the DC/EP remain opaque, but the PBOC has announced that the DC/EP will be distributed based upon a two-tier system: 1) between the central bank and commercial banks, and 2) between commercial banks and individuals or businesses.

Because the central bank will not directly issue DC/EP to consumers, it will not compete with commercial banks’ traditional business models. In the same way, Mu Changchun (穆长春), head of the DCRI, publicly clarified in October that the DC/EP will not compete with commercial digital payment platforms such as WeChat Pay and Alipay, which had a combined market share of 94 percent of the Chinese mobile payments industry in the second quarter of 2020 and recently came under anti-monopoly scrutiny. “They don’t belong to the same dimension.” Mu explained. “WeChat and Alipay are wallets, while the digital yuan is the money in the wallet” (SCMP, October 26, 2020).

This explanation is somewhat facile. Although technology giants like Alibaba and Tencent were once able to grow rapidly amid a relatively free regulatory regime and immature financial system, recent anti-monopoly crackdowns and a high-level financial de-risking campaign have clipped their wings (China Brief, December 23, 2020). While such companies previously out-competed Chinese commercial banks on the cutting edge of financial technology, the rollout of DC/EP will force them to interact on a newly leveled playing field. In a similar vein, while China has not passed legislation specifically banning cryptocurrencies, central government regulators ruled against initial coin offerings (ICOs) as being a form of illegal public financing in 2017 and the government does not recognize cryptocurrencies as legal tender (PBOC, September 4, 2017). As a result, there are essentially no privately issued digital currencies or ICO platforms in China (U.S. Library of Congress, updated July 12, 2018).

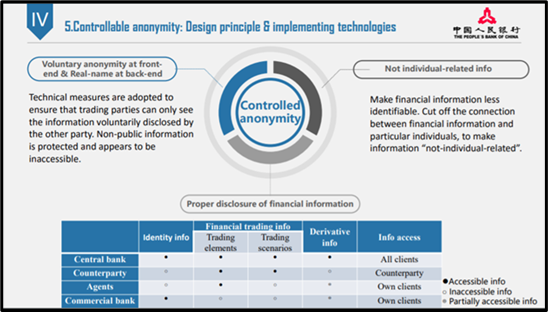

Foreign analysts have expressed concerns that the DC/EP could become another tool for China’s export of digital authoritarianism, warning that it could “create the world’s largest centralized repository of financial transactions data…[and] create unprecedented opportunities for surveillance.”[1] Researchers have questioned the strengths and limits of the DC/EP’s so-called “controllable anonymity” (可控匿名, kekong niming) (see image below). There are also strong concerns about whether or not the digital yuan has sufficient security provisions for protecting consumers’ data and preventing fraud (Quartz, October 26, 2020). Although China has aggressively pursued the “informatization” of its economy and society, its track record on data protection and consumer privacy has been less than ideal. Some have also questioned the organization of DC/EP’s two-tiered system. Multiple digital wallet operators could lead to data fragmentation or information silos (China Briefing, February 8). And, because DC/EP is entirely virtual, even state policymakers have worried that it could increase currency volatility (Xinhua, April 20, 2020).

Conclusion

Events last year increased the urgency for a Chinese digital currency. Guo Weimin (郭卫民), chief scientist at the state-owned Bank of China, said in January that the key advantage of the digital yuan would be its ability to trace cash flow in real time, permitting the better collection of debt and collateral during periods of economic stress such as a pandemic. Guo also suggested that the digital yuan could help solve age-old problems of transparency in corporate financing as well as having potential industrial and supply chain applications that would contribute to future growth (Sohu, January 24). And as already mentioned, successfully implementing the digital yuan would aid RMB internationalization, which has long been a priority for the Chinese leadership. CIPS, China’s current alternative to the global SWIFT system, has so far failed to gain serious international traction and currently processes a fraction of the daily transactions that go through SWIFT. Still, China’s trade and investment partners have increasingly settled transactions along the Belt and Road Initiative using CIPS, with the RMB being used to settle 20 percent of China’s foreign trade in 2020 (Atlantic Council, November 30, 2020). Successful cross-border adoptions of the DC/EP would aid this trend, creating another powerful lever to expand China’s international trade ties and influence.

Yet there are many outstanding questions about the safety and security of the digital yuan, as well as concerns about its implications for foreigners doing business with Chinese individuals or companies. Amid all this, China’s sprint to roll out the digital yuan over the next year will bear close watching.

Elizabeth Chen is the editor of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, feel free to reach out to her at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] For a detailed discussion of these concerns see: Samantha Hoffman, John Garnaut, Kayla Izenman, Matthew Johnson, Alexandra Pascoe, Fergus Ryan and Elise Thomas, “The Flipside of China’s central bank digital currency,” October 12, 2020, ASPI, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/flipside-chinas-central-bank-digital-currency; Yaya J. Fanusie and Emily Jin, “China’s Digital Currency: Adding Financial Data to Digital Authoritarianism,” January 26, 2021, CNAS, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/chinas-digital-currency.