China Pursues Ambitious, but Risky, Financial Reforms

China Pursues Ambitious, but Risky, Financial Reforms

China’s leadership has, in the past year, announced many reforms to the Chinese economy, and especially the country’s financial system. Some are slated to be implemented over time, while some are already in the process of being implemented. How can we distinguish between the two, and what should we expect in the coming months?

First, several major financial reforms have been announced and implemented in the past year. These include the July 2013 removal of controls on bank lending rates, the September 2013 announcement of the formal opening of the Shanghai Free Trade Zone, and the December 2013 issuance of negotiable certificates of deposit (PBOC “Notice on Furthering Market-Based Interest Rate Reform,” July 22, 2013; “Framework Plan for the China (Shanghai) Pilot Free Trade Zone,” September 2013; PBOC “Interim Measures for Interbank Deposits,” December 8, 2013).

The July 2013 removal of controls on bank lending rates was announced by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) as a step toward full bank interest rate liberalization. PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan later announced that deposit interest rate ceilings would be removed in the next one to two years (PBOC “Notice on Furthering Market-Based Interest Rate Reform,” July 22, 2013; Caijing, March 11). This reform was made effective immediately but had little real impact on lending rates, as most lending rates were already at or above the benchmark rate of 6 percent. The move was considered symbolic progress toward further interest rate marketization.

The Shanghai Free Trade Zone began operations in September 2013, with the stated aim of experimenting with reforms in interest rates and capital account openness. The Zone has already welcomed consulting companies to help domestic and foreign companies set up businesses inside the zone, but little progress has been made in implementing the promised reforms, and it has failed to attract a significant number of foreign enterprises. However, the Zone has lifted deposit rates on foreign currency deposits under $3 million, allowed cross-border RMB settlement to occur, and allowed the extension of overseas RMB loans, with certain restrictions. The Zone is a step toward liberalization of the exchange rate and capital account.

Issuance of negotiable certificates of deposit was also permitted as of December 2013; these instruments are traded on the interbank market and provide banks with another way to raise funds. Although less impactful than other reforms, this enhances the transparency of the interbank market.

Second, many economic and financial reforms were targeted at the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Communist Party Congress and the National People’s Congress. This includes a very long list that reflects the broad scope of the 12th Five Year Plan. Although many of the economic reforms impact the financial sector, for the sake of limiting the discussion we focus on projected financial reforms (Xinhua, March 15). The financial reforms within this list include: Setting up small- and medium-sized private banks, implementing a deposit insurance system, enhancing the stock issuance process, continuing with the deregulation of interest rates, improving the Internet banking sector, creating a market-based exchange rate system, increasing cross-border use of the RMB and increasing the capital account convertibility of the RMB. Closely related economic reforms include easing foreign investment in several sectors, including the banking sector; reducing barriers to international investment by Chinese enterprises; encouraging an increase in private investment; and reducing government investment in for-profit infrastructure projects.

The Chinese leadership generally keeps the details of the reform processes, such as the timetable, private until they go live, but some officials have hinted about certain reforms, including the deposit insurance system, interest rate liberalization, creation of private banks, regulation of the Internet banking sector and currency reform in public appearances or communiqués. In his state-of-the-nation address at the National People’s Congress, Premier Li Keqiang said that the deposit insurance system would be initiated and further interest rate liberalization carried out this year (Xinhua, March 14). The launch of pilot programs to set up five private banks in Tianjin, Shanghai, Zhejiang and Guangdong this year was announced by Chairman of the China Banking Regulatory Commission, Shang Fulin, at a press conference during the National People’s Congress (Xinhua, March 11). The People’s Bank of China has drafted some regulations to reduce risks in the Internet banking sector, to protect user information and data. Currency reform may already be beginning, as the People’s Bank of China announced in mid-March a widening of the RMB-dollar trading band to 2 percent (PBOC “PBC Public Announcement [2014] No. 5,” March 17). PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan stated in November 2013 in a guidebook explaining Third Plenum decisions that the central bank would exit interventions in the currency market; completion of this process is projected to happen by 2020 (Xinhua, November 15, 2013). What all of this means is that several major financial reforms are expected to be undertaken in 2014.

The most wide-reaching of both classes of reforms—those that were implemented this year, and those that were announced—are liberalization of interest rates and increased marketization of the exchange rate. These are fundamental, institutional reforms that will allow China to move closer (although certainly not completely) to a model of free market finance. Without these key changes, a continued move toward a market economy would be very difficult to pursue.

Lifting the lending rate floor was a symbolic move toward full interest rate liberalization, which will allow depositors to achieve higher returns on their deposits and discourage individuals from looking to riskier financial sectors for higher returns. Bank interest rates determined on the market as a result of interest rate liberalization will feed into the Shanghai Interbank Offer Rate, or SHIBOR, and improve the pricing of other financial instruments, such as corporate bonds. This will allow China’s financial system to become less policy-driven and more interest rate-driven, especially as state owned enterprises are pushed by higher lending costs to increase the efficiency of their use of bank capital.

Increased marketization of the exchange rate will have a strong impact on trade, as export and import prices fluctuate within the liberalizing band. If the exchange rate liberalization eventually results in appreciation of the currency, as it is widely expected to do, this will force export-oriented industries to become more competitive and will allow households to purchase a larger basket of goods from abroad, boosting imports. Some critical industries may remain protected as they are exposed to increased foreign competition, but the manner in which they are protected is up for debate. Subsidies to critical sectors like steel, for example, have already resulted in international outcry as overproduction has flooded global markets. The gradual removal of distortions imposed by the fixed exchange rate, guaranteed loans for inefficient investment and controlled interest rates will reduce the ability of the leadership to manage key sectors, and this issue will have to be addressed.

Elimination of government intervention in the currency market by 2020 will sharply reduce China’s need to build up dollar reserves to maintain the value of the currency, which will have large knock-on effects on American debt. A simultaneous increase in capital account convertibility of the RMB will provide a pressure valve on “hot money” flows; however, complete capital account convertibility, which is likely to be slower in coming, must be closely monitored to prevent too much “hot money” from entering or exiting the economy and setting the stage for financial crisis. This can sharply impact the real economy, as well as asset and commodity prices. Hence a balance in capital account convertibility is essential for the stability of both Chinese and global markets.

Thus far, the reforms that have been carried out have not had a significant impact on the business community, which has been more focused on events like the U.S. Federal Reserve’s tapering policy and the recent exchange rate depreciation of the RMB against the dollar. The reduction of uncertainty through the announcements of increased financial reform has on average bolstered global stock markets, while expectations on the ground regarding the reform process have been mixed. Some business analysts predict potentially strong and negative short-term impacts of financial reforms, particularly if the reforms are implemented rapidly and create clear losers, with long-term benefits of marketization. Others view the reforms as generally positive in terms of promoting productivity and efficiency among firms. At this point, however, there is no clear, unified reaction to these reforms within the business community.

China has some very large reforms on the agenda that address the very nature of its financial system, correcting fundamental distortions and increasing the presence of market forces. These reforms will affect many aspects of the Chinese financial and real economy, and, although they are positive moves toward more efficient allocation of capital, will have to be watched carefully for unexpected adverse effects. A focus on institutionalizing transparency and reducing related policy biases are essential to the success of these reform processes. Increased rebalancing of the economy toward new sources of profitability, such as consumption-related industries, can result in economic growth that will create an opportunity to reduce government intervention in the economy—but not a guarantee that state enterprises will not find ways to maintain their current standing.

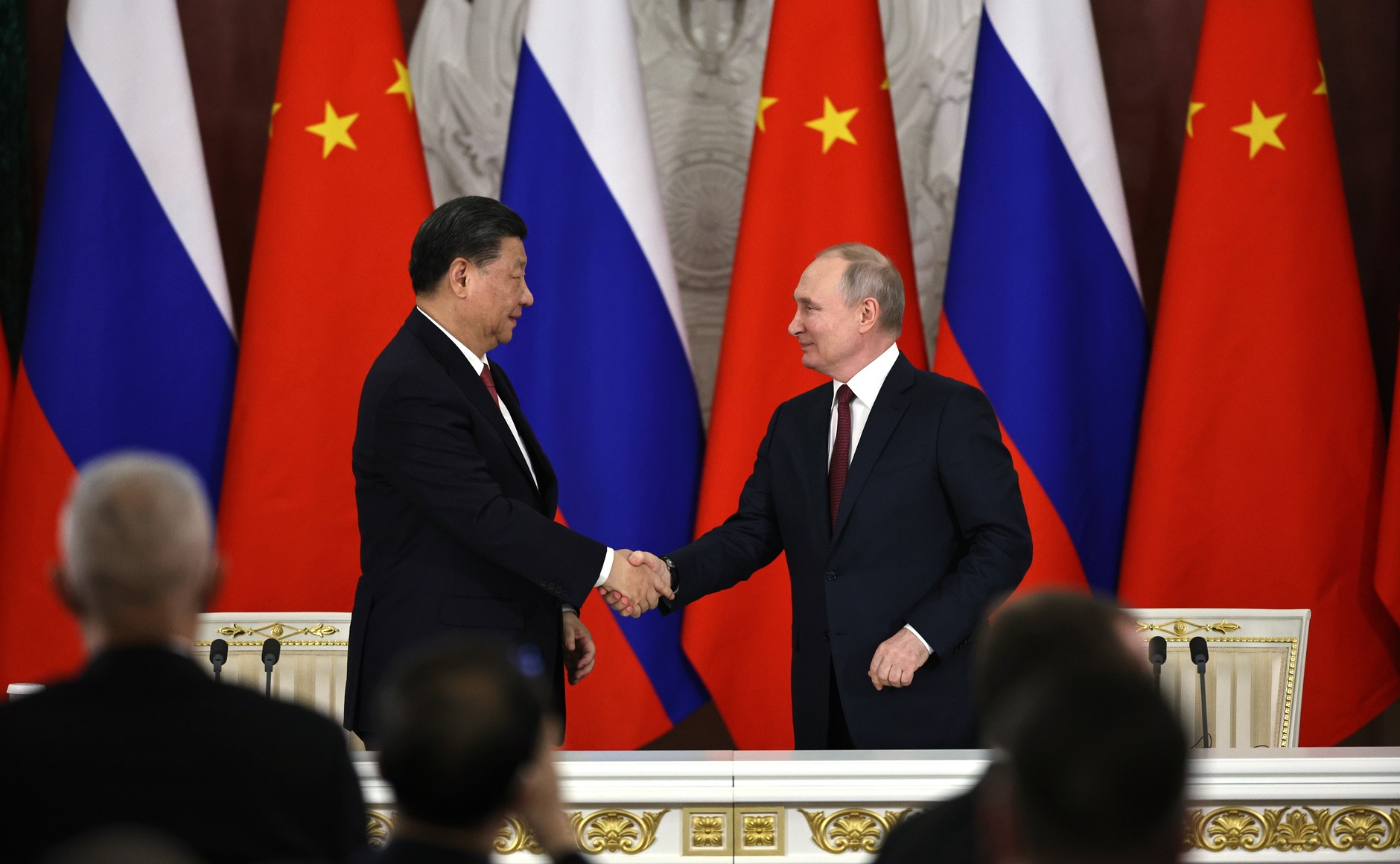

Much is riding on the success of the Xi-Li administration’s reforms. Many elements of this ambitious agenda have been slated for implementation in the coming months, yet, due to the complexity of realizing all of these changes, analysts wait with bated breath to measure their success. One can only hope that technocrats in Beijing are agile enough to respond to unforeseen consequences of their plan.