China and Saudi Arabia Solidify Strategic Partnership Amid Looming Risks

China and Saudi Arabia Solidify Strategic Partnership Amid Looming Risks

While the wider Middle East remains convulsed by conflict and instability, China’s influence and interests in the region continue to expand in a familiar pattern. As the world’s largest consumer of energy overall and the world’s second biggest importer of crude oil, China’s Middle East policy continues to be driven by the need for secure sources of energy. The China National United Oil Company (Chinaoil), a joint subsidiary of China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and Sinochem Corporation, alone purchased 7 million barrels of Middle East crude in January 2017 (Yibada.com [New York City], February 5). Unsurprisingly, China’s closest partner in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia is home to roughly 18 percent of the world’s total oil reserves and is the world’s top exporter of crude. The two countries’ relationship was solidified in 2009 when China surpassed the United States as the top destination of Saudi oil exports. Although Russia overtook Saudi Arabia as China’s number one supplier of oil in 2016, China’s reliance on Saudi oil will remain central to its energy security calculus (Gulf Business [Dubai], January 17).

However, multiple state-level bilateral exchanges in 2016 point to an evolving relationship that transcends oil. Sino-Saudi relations witnessed an unprecedented expansion in bilateral security cooperation in 2016 in the form of their first ever joint counterterrorism exercise (al-Jazeera [Doha], October 23, 2016). The increasing pace of Sino-Saudi contacts points to a more expansive phase of bilateral relations over a convergence of interests in the security sphere. The increasingly security-focused elements on display in China’s relationship with Saudi Arabia represent the latest sign of China’s growing appetite for showcasing its military capabilities beyond its borders. At the same time, given Saudi Arabia’s predicament, China’s growing engagement with the kingdom exposes it to a multitude of risks.

Energy, Economics, and Diplomacy

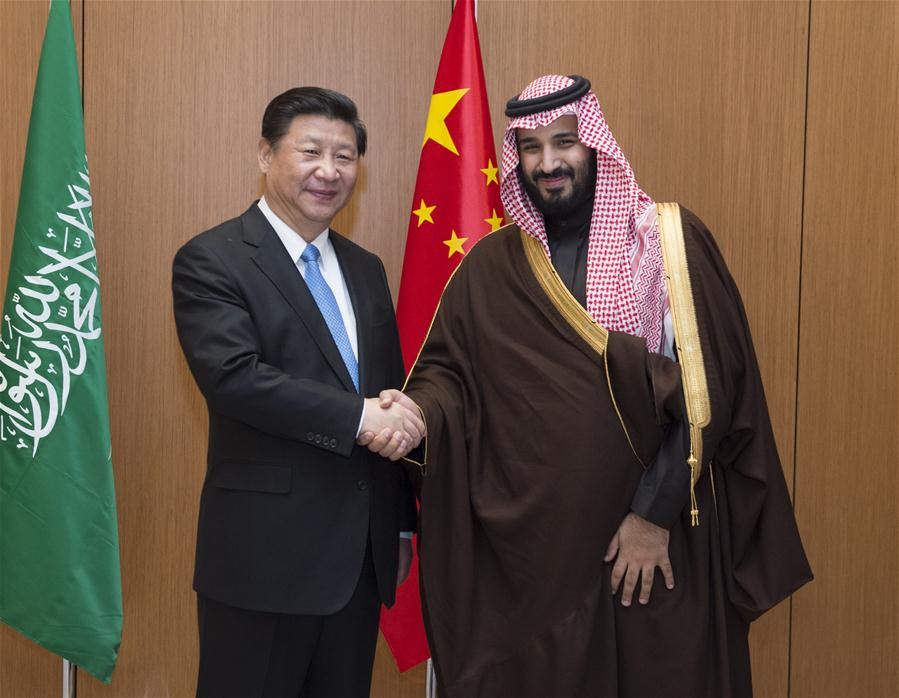

The outcome of the Saudi Deputy Crown Prince Muhammed bin Salman al-Saud’s three-day visit to Beijing in August 2016 is further illustrative of the growing amity between China and Saudi Arabia. The ambitious and multi-titled grandson of King Salman bin Abdulaziz al-Saud—Prince Salman also serves as Saudi Arabia’s second Deputy Prime Minister and Defense Minister—has emerged as the face of the kingdom’s drive to reform, modernize, and diversify its economy under its Vision 2030 plan (al-Arabiya [Abu Dhabi], April 26, 2016). Salman visited at the invitation of Chinese Vice Premier Zhang Gaoli, shortly ahead of the September 4–5 meeting of the eleventh annual meeting of the Group of 20 (G20) in Hangzhou. Salman’s meetings with Vice Premier Zhang yielded fifteen memorandums of understanding (MOUs) governing cooperation in the energy, mining, housing, finance, infrastructure, and public works sectors. The MOUs also outlined plans to help finance reconstruction projects in areas affected by earthquakes in China, collaboration between the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology and King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, and future cultural exchanges. Prince Salman also met with officials representing the Bank of China, Bank of China for Telecommunications, and the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank (Asharq al-Awsat [London], August 30, 2016). The two sides also announced the creation of a joint bilateral strategic body to act as a framework for future bilateral contacts (al-Arabiya, August 30, 2016; Xinhua, August 30, 2016). Prince Salman also met with China’s Defense Minister Chang Wanquan in an exchange that yielded a commitment to further advance Sino-Saudi security cooperation (Xinhua, August 31, 2016).

Similarly, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s January 2016 visit to Saudi Arabia yielded a host of energy and trade agreements. China imported approximately 1 million barrels per day of crude oil in 2016 from Saudi Arabia, accounting for around 20 percent of its overall energy demand (Gulf Business, January 17). China is also Saudi Arabia’s biggest oil customer and overall largest trading partner. Xi’s visit was the first stop on a three-nation Middle East tour that would also bring him to Egypt and Iran. His trip was the first by a Chinese president to the kingdom in seven years. Xi’s talks with King Salman resulted in the elevation of the current bilateral relationship to what was termed a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” Both leaders appeared side-by-side at the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center in Riyadh to remotely inaugurate the Yanbu Aramco Sinopec Refining Company (YASREF) oil refinery (YASREF, February 9, 2016; Xinhua, January 21, 2016; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, January 20, 2016). Located in Yanbu Industrial City along the Red Sea in the kingdom’s al-Medina Province, YASREF represents a joint venture between the Saudi Arabian Oil Company (Aramco) and the China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Sinopec). Initiated in 2012 at an initial investment of $10 billion, the effort represents China’s single-largest investment in Saudi Arabia. Aramco holds a 62 percent stake while Sinopec holds a 37 percent stake in YASREF (YASREF, February 9, 2016). YASREF is a full-conversion refinery and the first overseas refinery constructed by Sinopec.

Xi used the occasion to praise the state of Sino-Saudi relations and emphasize the kingdom’s role in China’s OBOR initiative. Recognizing the significance of China’s emphasis on establishing a web of regional trade and communication lines, Saudi Arabia has since expressed interest in joining the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) (Express Tribune [Karachi], October 1, 2016). Both sides also reiterated their agreement on a range of range of regional topics, including combatting terrorism. Numerous agreements governing cooperation in the energy, communications, technology, environment, culture, aerospace, and scientific sectors were also concluded (Xinhua, January 21, 2016).

As the last country to recognize the People’s Republic of China in 1990, Sino-Saudi relations have grown markedly from their previous state of passive indifference to Cold War tensions. Saudi Arabia’s strategic alliance with the United States took precedent over all else in foreign affairs. The changing geopolitical landscape has prompted Saudi Arabia to revise its foreign policy. Much has been said of former U.S. president Barrack Obama’s declaration of a U.S. strategic pivot towards Asia. Saudi Arabia has initiated its own strategic pivot of sorts toward Asia and, in particular, China (al-Monitor, March 13, 2014). In doing so, Saudi Arabia is seeking to diversify its portfolio of foreign relations to offset what it perceives to be a decline in U.S. global influence and a shift in the U.S. Middle East calculus. Saudi trepidation over the prospects of a U.S. détente with Iran, disagreements over the conflict in Syria, and a host of other issues have propelled the kingdom to seek out new partners.

China’s highly touted friendship with Iran also is likely to weigh heavily on Saudi thinking. In this context, Saudi Arabia’s overtures to China also reflect an effort to offset the extensive inroads that have already been achieved in Sino-Iranian relations. A visit by a delegation representing Yemen’s Houthi rebellion to Beijing in November 2016 is also likely to have raised suspicions about China’s intentions in Yemen’s civil war given the diplomatic efforts to end the conflict. Saudi Arabia is determined to reverse Houthi gains through military action and reassert its influence in Yemen while China has advocated for a peaceful resolution of the conflict (Middle East Observer [Stockholm], December 3, 2016; al-Araby al-Jadeed [London], December 1, 2016). China’s continued support for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in Syria represents another potential concern given Saudi Arabia’s support of efforts to topple the Ba’athist regime. During an August 2016 meeting with Syrian Defense Minister and Deputy Prime Minister General Fahd Jasim al-Furayj in Damascus, Chinese Rear Admiral Guan Youfei reaffirmed China’s support for the Ba’athist regime and relayed a commitment to increase Sino-Syrian military cooperation. Youfei also conveyed China’s concerns about the prevalence of Chinese and other ethnic Uighur militants associated with the al-Qaeda-affiliated Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) who have joined the most radical factions within the Syrian insurgency (Diplomat [Tokyo], January 27; South China Morning Post [Hong Kong], August 16, 2016). TIP is implicated in a host of attacks in China’s Xinjiang-Uighur Autonomous Province and beyond.

Security Affairs

Unlike its energy, economic, and diplomatic aspects, the security dimension of China’s relationship with Saudi Arabia has received less scrutiny. Historically, the security dimension in Sino-Saudi relations has been quite limited. The extent of Sino-Saudi security relations is generally attributed to Saudi Arabia’s acquisition of China’s Dongfeng-3 (DF-3; NATO CSS-2 [“East Wind”]) nuclear-capable intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) in the late 1980s (China Brief, October 24, 2002). The conclusion of the missile deal occurred prior to the 1990 establishment of formal diplomatic relations between both countries. Saudi Arabia is also known to have subsequently acquired DF-5 (CSS-5) intercontinental ballistic missiles from China. Saudi Arabia is also reported to have procured the yet more advanced DF-21 missile system in 2007, allegedly with U.S. approval (Middle East Institute, February 9, 2016; Nuclear Threat Initiative, August 2015; Defense-Update [Qadima], May 2, 2014; Diplomat, January 31, 2014). Saudi Arabia’s pursuit of Chinese ballistic missile platforms served to enhance the kingdom’s deterrent capacity against Iran, Iraq, and Israel after its requests for U.S. missile and other advanced defense systems were rejected. The Chinese-supplied missiles are operated by the Royal Saudi Strategic Missile Force and are deployed in numerous locations, including the Al-Sulayyil Strategic Missile Base, southwest of the capital Riyadh. It is one of at least two missile bases reportedly constructed by China in the 1980s (ababiil.net [Yemen], July 1, 2015).

The security umbrella afforded by the longstanding U.S.-Saudi strategic relationship remains the foundation of the kingdom’s national security strategy. Saudi Arabia’s reliance on U.S. weapons platforms is further illustrative of its dependence on the United States. Saudi Arabia is one of the world’s largest importer of weapons, having surpassed India in 2014 as the single-largest arms importer overall. The kingdom is also the single-largest importer of U.S. defense systems (SIPRI, February 2016). Nevertheless, Saudi Arabia has demonstrated at least a passing interest in purchasing additional Chinese defense systems, including the jointly produced Chinese-Pakistani JF-17 fighter (The News International [Karachi], November 17, 2016). Saudi Arabia is also reported to have reached a deal with China’s Chengdu Aircraft Industry Group (CAIG) for the purchase of a number of medium-altitude, long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) capable of conducting intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance operations as well as targeted strikes (Arab News [Jeddah], September 1, 2016). Saudi Arabia is also rumored to have expressed an interest in potentially developing a submarine with Chinese assistance (Tactical Report [Mansourieh], September 2, 2016).

President Xi’s January 2016 visit to Saudi Arabia yielded a commitment from both sides to increase bilateral security cooperation, especially in the counterterrorism arena (Xinhua, January 20, 2016). A delegation led by Meng Jianzhu, a special envoy of Xi’s, traveled to Riyadh in November 2016 to meet with King Abdulaziz to discuss a range of security issues. Both sides announced a commitment to forge a five-year plan to increase bilateral security cooperation (Arab News, November 7, 2016; Middle East Observer, November 7, 2016). Jiazhu’s visit followed a milestone in Sino-Saudi security relations. China and Saudi Arabia staged their first joint counterterrorism exercise in October 2016. Dubbed “Exploration 2016,” the exercise was held over a fifteen-day period in China’s southwestern city of Chongqing. The exercise featured Special Forces units attached to the Royal Saudi Land Forces and their People’s Liberation Army (PLA) counterparts. The exercises, which featured two 25-member contingents representing both countries, were designed to improve the respective capacities of both countries to conduct counterterrorism, hostage rescue, and other complex operations (South China Morning Post, October 27, 2016; Asharq Al-Awsat, October 27, 2016; Asharq Al-Awsat, October 23, 2016).

Looming Risks

A snapshot of Saudi Arabia’s geopolitical picture reveals some of the risks China faces as its engagement with the kingdom grows. Despite its autocratic character, Saudi Arabia has been spared the wave of upheaval witnessed elsewhere in the Arab world. Even as it confronts a domestic terrorist challenge in the form of a resilient al-Qaeda and self-anointed Islamic State, heightened sectarian tensions, and growing displays of popular dissent, Saudi Arabia has managed to present an image of constancy. Its reality is far more complex. Saudi Arabia is beset with a litany of challenges to its domestic security, political stability, economic viability, and regional standing. The fall of oil prices has undermined the kingdom. The removal of a number a number of economic sanctions levied against Iran following the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action agreement has helped facilitate the steady return of Saudi Arabia’s archrival into energy markets. The growth of the U.S. shale industry has likewise helped to chip away at the kingdom’s comparative advantage in the oil sector. In a measure designed to help bolster oil prices, Saudi Arabia helped the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries reach an agreement to slash production, but any short-lived increases in the price of oil are not likely to offset the kingdom’s many structural challenges (Economist [London], December 3, 2016). Given the blows to China’s interests in Egypt, Libya, Syria, and other Arab countries beset by instability in recent years, the potential destabilization of Saudi Arabia would have major repercussions for Chinese interests. Saudi Arabia’s problems extend to the foreign policy front. Saudi Arabia’s intervention in Yemen has been disastrous. Saudi Arabia has also failed to achieve its objectives in Syria and other fronts. Despite its official repudiation of extremism, Saudi Arabia remains the ideological wellspring of the austere Wahhabist and Salafist philosophies that have helped to nurture violent radical Islamist currents worldwide. This includes ideological movements that have helped spawn extremists in China or are otherwise targeting Chinese interests abroad.

Conclusion

While Sino-Saudi relations will continue to flourish, the kingdom’s precarious geopolitical predicament exposes China to multiple energy and economic risks. The security facets of the bilateral relationship will likely draw the most attention, although are no indications that they will exceed its energy, economic, and diplomatic facets even as the kingdom is likely to invite closer security cooperation. Despite its impressive inroads, China is in no position to displace or otherwise categorically offset U.S. influence in Saudi Arabia or the wider Middle East. Just as important, there are no indications to suggest that China has its sights set on overtaking the United States as the region’s dominant military actor. Saudi Arabia remains a critical member of an entrenched U.S. regional alliance network, a reality that is not likely to have been lost in Beijing. At the same time, China’s rising influence in the Middle East does provide it with tangible strategic advantages, including crucial leverage that could be brought to bear over the United States in a future crisis in the South China Sea or other possible friction points in Asia or elsewhere down the line.

Chris Zambelis is a Senior Analyst specializing in Middle East affairs for Helios Global, Inc., a risk management group based in the Washington, D.C. area. He is also the director of World Trends Watch, Helios Global’s geopolitical practice area. The opinions expressed here are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of Helios Global, Inc.