China’s Declining Influence in Nepal: Implications for the U.S. and India

Publication: China Brief Volume: 22 Issue: 7

By:

Introduction

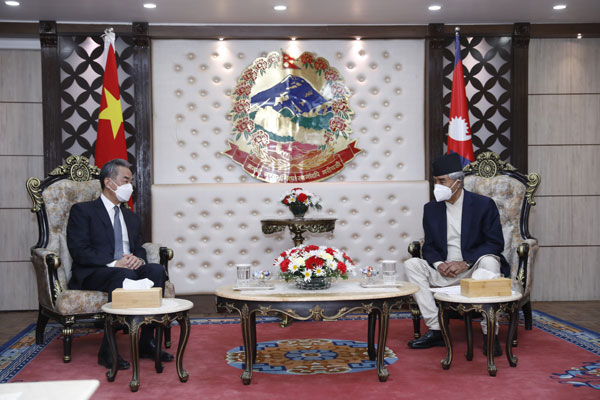

During Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Kathmandu on March 25-27, China and Nepal signed nine agreements covering an array of fields including a technical assistance for a cross-border railway feasibility study, economic, and technical cooperation, and COVID-19 vaccine assistance to Nepal (Kathmandu Post, March 26). However, none of the agreements concerned Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects (Kathmandu Post. March 27). In the run-up to Wang’s visit, Nepali media cited government sources that the visit’s “major purpose” was “to push for the implementation of the BRI and sign at least two projects during the visit if possible.” A senior Nepali government official stated “we have already received the text of the project implementation plan of the BRI from China,” which will lay the groundwork for the execution of future projects (Kathmandu Post, March 15).

Since 2015, China’s political influence and economic presence in Nepal have witnessed remarkable growth. However, the failure of Nepal and China to finalize any BRI projects while Wang was in Kathmandu represents an unexpected setback to Chinese interests in the Himalayan country. It comes less than a month after the Nepali parliament ratified the controversial Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compact, a $500-million U.S. grant for the development of power transmission and road construction projects, which makes the situation particularly mortifying for Beijing. What do these developments portend for Sino-Nepali relations, as well as for the Sino-Indian geopolitical rivalry playing in Nepal and the broader region?

Limited Interaction

Nepal and China became neighbors only after Beijing’s annexation of Tibet in 1950, prior to which Nepal shared borders with Tibet. For decades thereafter, Chinese influence in Nepal failed to meet Beijing’s expectations for two main reasons. First, the Himalayas are a formidable barrier to connectivity and trade between the two countries. Second, India wields enormous influence in landlocked Nepal, which is economically reliant on its southern neighbor. India is Nepal’s largest trade partner and is the destination for 74 percent of its exports. Almost all of Nepal’s third-country trade transits through India (Embassy of India, July 2, 2021). Furthermore, the 1950 India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship requires Nepal to consult India on defense and foreign policy issues. [1] Given its long-running geopolitical rivalry with China, India has ensured that Nepal remained firmly in its sphere of influence for decades.

Nepal’s importance to China stems from its location: Nepal shares borders with Tibet to its north and India to its south. With a large number of Tibetans seeking refuge in Nepal, China needed a friendly government in Kathmandu to clampdown on Tibetan activism and also to prevent the U.S. and India from channeling support for anti-China activism inside Tibet through Nepal. Additionally, Nepal could act as a corridor for China to access India’s vast market (China Brief, November 16, 2015). Hence, China has had clear strategic interests in building a strong relationship with Nepal.

China’s Growing Role in Nepal’s Economy

Despite the challenges posed by the geographic barrier of the Himalayas and India’s firm influence, China has made inroads into Nepal, especially in recent decades. This progress was facilitated in part by Beijing’s growing economic capacity to build infrastructure projects in Nepal and by the outreach of successive Nepali governments, who, anxious to counterbalance India’s overbearing presence with that of China, wooed Beijing. This prompted King Mahendra to court Beijing in the 1960s. Chinese infrastructure projects including the Kathmandu-Kodari highway, which links the Nepali capital with the Chinese border, were completed in this period (Xinhua, March 4, 2017). In 2005, when India halted military supplies in response to King Gyanendra’s authoritarian moves, the Nepali monarchy turned to Beijing, which moved in swiftly to supply Nepal with weapons (China Brief, November 16, 2015).

China also grew from a “marginal” lender in the early 2000s to become Nepal’s top investor in 2014. China’s role in Nepal’s economy received a huge boost in 2015-16, when India imposed an ‘unofficial blockade’ on Nepal that lasted for several months. The ensuing scarcity of fuel, medicine, and other essential commodities triggered a tidal wave of anti-India sentiment in the country. The Nepali government turned to China, which stepped in to supply gasoline, breaking India’s monopoly on fuel sales to Nepal (China Brief, November 16, 2015). Several agreements followed, including the Transit Transport Agreement, under which China provided Nepal with seven transit points—four sea ports and three land ports—for trade with third countries. Such agreements sought to limit Nepal’s extreme dependence on India for global trade access, and consequently reduce its vulnerability to Indian pressure (Kathmandu Post, January 2, 2020).

In 2018, Nepal signed a Framework Agreement to join the BRI. Kathmandu embraced the Chinese initiative as it presented the landlocked country with opportunities to build its infrastructure, improve connectivity, access global markets, and reduce its deep dependence on India. The two countries identified nine projects for potential BRI funding. These included four road projects, two hydroelectricity projects, one cross-border railway, one cross-border power transmission line, and one technical institution (Kathmandu Post, January 18, 2019). China’s share of Nepal’s total foreign direct investment (FDI) surged from 42 percent in 2015-16 to a staggering 95 percent in early 2021 (Gateway House, September 16, 2016; Xinhua, September 16, 2021).

China’s Clout in Nepali Politics

China’s rising political clout in Nepal is built on its growing economic presence. When Nepal became a republic in 2008, China lost its main patron—the monarchy—and therefore began cultivating Nepal’s communist parties. These efforts have been fruitful. During the presidency of Pushpa Kamal Dahal, the former Maoist chief, Nepal joined BRI and also enabled China to play a pivotal role in government formation.

Soon after an alliance of the Communist Party of Nepal-United Marxist Leninist (CPN-UML) and the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist Center (CPN-MC) swept parliamentary elections in December 2017. Vice Minister of the International Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Guo Yezhou, reportedly worked to unite the two parties (Kathmandu Post, February 21, 2018). In May 2018, Nepal’s two largest communist parties merged to form the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) in May 2018, which provided Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli with a majority government. Political and ideological consultations and bonds grew between the Nepali and Chinese communist parties. CCP officials held training sessions for NCP leaders and grassroots workers on “Xi Jinping Thought” (The Himalayan, September 23, 2019, September 25, 2019). In October 2019, Chinese President Xi Jinping traveled to Nepal, which was the first visit by a Chinese president in over two decades (Xinhuanet, October 12, 2019). During the visit, the two sides signed 20 agreements, marking the apogee of China’s influence in Nepal (Himalayan Times, October 14, 2019).

Under the NCP government, Nepal’s foreign policy tilted away from India toward China. Oli took increasingly hostile positions vis-à-vis India, accusing it of trying to oust him from power and encroaching into disputed territory in the Lipulekh-Kalapani-Limpiyadhura area. He went on to alter Nepal’s maps to show this territory as part of Nepal, and even amended the constitution to make the new map official (The Hindu, June 18, 2020). Indian Army chief M M Navarane said that the allegations against India were “at the behest of someone else,” hinting at a possible Chinese role in the charges (The Wire, May 15, 2020). As a result, anti-India protests raged in Nepal.

China had high stakes in the survival of the NCP-majority Nepali government. Consequently, when a power struggle broke out in 2020 between Oli and Dahal, chairperson and co-chairperson of the NCP, respectively, Beijing swung into action. The Chinese ambassador to Nepal Hou Yanqi engaged with top leaders in an effort to keep the NCP united. Her direct access to Nepali officials and leaders, including President Bidhya Devi Bhandari, Oli, and Dahal raised eyebrows in the region (Deccan Herald, December 27, 2020). When Hou’s mediatory efforts failed, Beijing rushed a team led by Guo to save the government (The Himalayan, December 30, 2020). However, China’s dogged mediation efforts failed to forestall a split in the NCP and the Maoist government collapsed.

Setbacks for China

The exit of the NCP from power resulted in a government led by the Nepali Congress (NC)—a party that is seen as more aligned with India’s interests—taking charge in Kathmandu in July 2021. Since then, there has been a marked toning down in the Nepali government’s criticism of India. Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba’s silence on India’s road widening activity in the Lipulekh-Kalapani-Limpiyadhura area prompted criticism from the public and political opposition (Nepal Live Today, January 9).

Since the exit of the NCP government, Chinese interests have suffered a setback in Nepal in recent months. Developments relating to the MCC and BRI projects lay bare China’s declining ability to influence Kathmandu’s decisions. China tried hard to stall the MCC compact’s ratification by the Nepali parliament. The Chinese Foreign Ministry strongly criticized the U.S. for its “coercive diplomacy” and “infringement” of Nepal’s sovereignty “for selfish gains” (Annapurna Express, February 23). Despite Beijing’s reservations, the Nepali parliament nevertheless ratified the compact on February 27 (Deccan Herald, March 5). Beijing’s inability to prevent the MCC compact’s ratification signal its declining influence in Kathmandu.

As for the fate of BRI projects, despite the initial enthusiasm, not a single project has taken off over the past five years. Political turmoil in Nepal is partly to blame for the lack of progress under the NCP government, but the failure of the two sides to finalize projects during Wang’s recent visit indicates that the NC government is taking a tough position on negotiating project terms. During discussions with Wang, the Nepali side reportedly insisted that the Chinese provide grants rather than loans, or at very least, soft loans. The Nepali side even set a cap on the interest that the Chinese could charge. They also told the Chinese that bids for project implementation should not be restricted to Chinese firms (Katmandu Post, March 27). Nepali Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba appears to be leveraging the MCC grant from the U.S. to secure better financing terms from Beijing for BRI projects (The Diplomat, March 30).

Conclusions

China’s failure to prevent the ratification of the MCC compact and to bring Nepal on board with BRI projects on its terms signal a reduction in Beijing’s capacity to influence policy and decision making in Kathmandu. This decline could impact China’s strategic and economic interests in several ways. The future implementation of the MCC will enhance the U.S. presence and influence in Nepal. As Indian and American interests in Nepal coincide, the rise of American influence will help India in its geopolitical competition with China in Nepal. The connectivity and power projects envisaged under the MCC will also provide Indian economic and other interests in Nepal with a shot in the arm. Overall, this round of the geopolitical battle between China on the one hand and India and the U.S. on the other, has gone in the latter’s favor.

However, it is not the end of the road for China in Nepal. Beijing has worked systematically to build support for itself not just with Nepali politicians but also among the media, business community, and general public. This broad support for China and its BRI projects has not disappeared. Public sentiment against India is still far greater than against China and can be easily triggered to stir up mass unrest. Furthermore, the NC government is a minority government that is fragile and vulnerable to pressure. Therefore, a return of Beijing-preferred political parties and politicians to power in Nepal cannot be ruled out.

Dr. Sudha Ramachandran is an independent researcher and journalist based in Bangalore, India. She has written extensively on South Asian peace and conflict, political and security issues for The Diplomat, Asian Affairs, and the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor and Militant Leadership Monitor. She can be contacted at sudha.ramachandran@live.in