China’s East China Sea ADIZ: Framing Japan to Help Washington Understand

Publication: China Brief Volume: 13 Issue: 24

By:

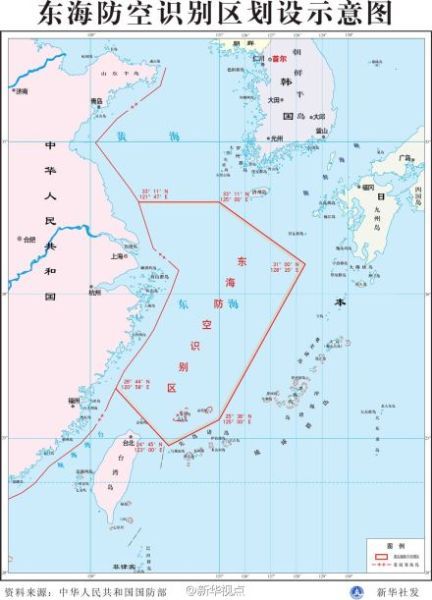

On November 23, Beijing announced that a new Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) would go into effect over the East China Sea, overlapping existing Japanese and South Korean ADIZ, requiring all air traffic passing through the zone to file flight information irrespective of its destination. Despite eliciting strong responses from Tokyo and Washington as well as restrained but negative responses from Seoul, Taipei and Canberra, China claimed the ADIZ was a routine measure for improving awareness of its airspace and protecting its national security without any ulterior motive (China Daily, November 30; PLA Daily, November 27; Xinhua, November 25; Yonhap News, November 25, Xinhua, November 23). Maintaining an ADIZ is a relatively common practice, but Beijing’s justification for the new zone rested explicitly on its disputed claim over the Diaoyu (or Senkaku) Islands (Xinhua, November 25). From the beginning, Beijing has appeared prepared to address specific foreign concerns, manage diplomatic backlash, and coordinate the launching and publicizing of air patrols. This suggests a deliberate action, even if the reasons for why now remain mysterious. The ways in which Beijing described the ADIZ’s establishment indicates China has used this opportunity not only to reinforce its claim on the Diaoyu Islands, but also to drive a wedge between Japan and the United States.

The Execution of Policy, Not the Incitement of Crisis

One of the most notable features of China’s presentation of the ADIZ and its policies is the absence of crisis language. As Paul Godwin and Alice Miller have chronicled, Beijing makes steadily escalating statements prior to using military force—a feature noted in China’s wars since 1949. [1] The principle mouthpieces of the party, while refuting Japanese and U.S. protestations, have remained relatively tame in their language. Only one statement in an institutional, unsigned editorial in the military’s paper evoked this kind of warning:

In addition to the absence of crisis language from authoritative outlets, the ADIZ story was not initially played up in China media web portals and required deliberate interest in defense news to find. This further demonstrates China’s effort to present the formation of the ADIZ in a low-key manner.

Indeed, Beijing’s entire presentation of the ADIZ focuses on establishing China’s action as normal and legal as well as expressing China’s concern for peace. Institutional and expert commentaries in the days that followed the announcement were filled with annotations such as “having no intention to generate tensions,” “a move of justice to safeguard regional peace and stability” and the assertion the ADIZ “cannot be described as a threat to another country” (China Military Online, November 28; Xinhua, November 25; PLA Daily, November 25). The hawkish defense commentator Luo Yuan and National Defense University professor Meng Xiangqing even suggested the ADIZ, in the words of the latter, “will in fact bring more security for aircraft flying over the East China Sea. The zone will help reduce military misjudgment”—a position reiterated by the defense ministry this week (Xinhua, December 3; China-US Focus, November 27; Xinhua, November 26).

Four indicators strongly suggest the declaration of the ADIZ was a well-planned policy action that was coordinated across the government, or least among senior policymakers. Although China may be getting vastly better at crisis management and getting its message out, these indicators buttress the hypothesis that the ADIZ was deliberate, considered policy:

- Xinhua announced the ADIZ as a “Statement by the Government of the People’s Republic of China,” which is relatively rare and suggests a policy coordinated at the highest levels—the Politburo Standing Committee and possibly the Central Military Commission (Xinhua, November 23).

- Chinese diplomats in at least three countries—the United States, Japan and Australia—had prepared talking points to downplay the implications of the ADIZ as well as any suggestion that it affected the sovereignty disputes in the East China Sea (Xinhua, November 26; Xinhua, November 25; The Australian, November 25; South China Morning Post, November 25).

- A variety of Chinese military and legal experts across the PLA’s different institutions were prepared to discuss the ADIZ, its implications as well as its consistency with domestic and international law and treaty commitments. In addition to the Ministry of National Defense spokesmen, Beijing presented comments from the PLA Air Force, the PLA Navy and National Defense University as well as their affiliated education establishments (Xinhua, November 26; People’s Daily, November 24; Xinhua, November 24; Xinhua, November 23).

- Shortly after announcement of the ADIZ, Beijing dispatched and publicized its first aerial patrol of the newly-designated zone (People’s Daily, November 24; Xinhua, November 24).

Framing Tokyo for Washington’s Benefit

The careful control of the ADIZ presentation indicates that China’s story has a calculated message for a targeted audience. Although Beijing is demonstrating once again that the Diaoyu Islands are, in fact, disputed, the main messaging appears directed at Washington and its commitment to Japan. In many respects, the U.S.-Japan alliance and the basing of U.S. military forces is one of the keys to the military aspects of Washington’s “rebalancing toward Asia”—a feature recognized as such by Chinese analysts (PLA Daily, February 2; Dang Jian, January 18).

China’s propaganda presentation contains three themes relevant to the United States and aimed at driving a wedge between it and Japan. Although none of these are necessarily new, the ADIZ declaration offered an opportunity to use them within the context of an emerging crisis:

- Japan, not China, is the threat to regional peace and stability

- Washington is failing to live up to its commitments in the post-World War II world

- Tokyo is dragging the United States toward conflict

Japan, not China, is the Threat to Regional Peace and Stability:

Consistent with its past conflicts, Beijing has painted its actions as defensive and the internationally-recognized, appropriate reaction to the provocation of Japan’s military activities on its periphery (PLA Daily, November 27). Tokyo rather than Beijing, especially because of the government’s purchase of Diaoyu Islands last year, is portrayed as the real threat to the status quo and regional stability. MND spokesman Yang Yujun stated “Facts have proven that it is Japan who has been creating tense situations” or, as one unsigned editorial put it, “[Washington] should pin the blame on the real offender for changing the status quo in the East China Sea and undermining regional peace and stability” (Xinhua, November 25). In Beijing’s telling, the situation is only going to get worse as the return of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe presages a more firm Japanese policy—a process already begun. One of the institutional editorials protesting China’s innocence noted “Abe has taken a series of worrisome actions, including increasing Japan’s military budget for the first time in 11 years, staging more military exercises and even openly announcing the intention to revise Japan’s pacifist constitution” (Xinhua, November 25).

Washington is Failing to Live Up to Its Commitments in the Post-World War II World:

China has attempted to frame controlling Japan (and restraining its militarism) as part of the U.S. post-World War II international system. An unsigned Xinhua editorial stated Tokyo “has also rejected and challenged the outcomes of the victory of the World Anti-Fascist War” (Xinhua, November 25). MND spokesman Yang added “Japan also boosted its military capacity under various disguises, attempting to change the post-World War II international order” (Xinhua, November 29). One article appearing on a Central Party School-run news portal before the ADIZ announcement even equated Washington’s tolerance of rising Japanese militarism with appeasing Germany prior to the outbreak of World War II—something that provides an immediate palliative at the expense of long-term stability (Seeking Truth Online, October 23).

Beyond the issue of Japanese militarism, the 70th anniversary of the Cairo Declaration this month offered the opportunity to invoke the Allies’ commitment to restoring Chinese territories lost to Japan. The declaration stated “all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and Pescadores,” which was later reaffirmed by the Potsdam Declaration in 1945. China’s current interpretation is that this includes the Diaoyu, so “in international law, the Diaoyu Island and its affiliated islands have been returned to China since then” (Xinhua, December 1; Xinhua, November 25).

The other, more current, U.S. failure relates to China’s assessment that Washington has acted in bad faith over its commitment to not take a position on the sovereignty of the Diaoyu Islands. The official statements reacting to the ADIZ delivered by Secretary of State John Kerry and Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel along with the B-52 flights suggest, at least to Chinese analysts, that Washington already has taken a clear stand against China. As Su Xiaohui, a researcher at the MFA-run China Institute for International Studies, wrote, “[the United States] even pretended to have forgotten its consistent claim of holding no positions in the issue of the Diaoyu Islands while making stress on its obligation to its allied country” and reiterated its treaty commitment to help Japan defend the islands (People’s Daily Overseas Edition, November 28).

Tokyo is Dragging the United States toward Conflict:

The official Chinese press have castigated Washington’s responses to the establishment of the ADIZ, suggesting that the United States is emboldening an increasingly militaristic Japan and moving Beijing and Washington closer to conflict. Xinhua opined that “The U.S. overreaction has bolstered Japan intentionally or unintentionally,” allowing Tokyo to malignly influence U.S.-China relations (Xinhua, November 27). According to an English-language editorial, “Washington’s ‘message’ will only add fuel to Tokyo’s dangerous belligerence and further eliminate room for diplomatic maneuvers. More importantly, it may put China and [the United States] on a collision course” (China Daily, November 28). Elsewhere, Xinhua warned the United States that “keeping a blind eye to the dangerous tendency in Japan could prove to be risky and might even jeopardize the U.S. national interests” (Xinhua, November 25).

This theme raises the hope that, should Washington not support Japan, Sino-American competition and/or conflict may be averted. An editorial in the English-language China Daily addressed this directly: “The ‘more collaborative and less confrontational future in the Pacific’ [Kerry] envisages rests more on Japan being sensible and peaceful” (China Daily, November 26). A Japan not confident of U.S. support, according to the Chinese media, would be less prone to militarism and more likely to deal fairly with China over the future of the Diaoyu Islands.

Conclusion

At this early date, there seem to be few clear conclusions about Beijing’s intensions in announcing an ADIZ. First, there seems little doubt that this was a coordinated policy that was executed at a time of Beijing’s choosing. It is not a policy free-for-all, but rather another calculated step that reinforces Chinese territorial claims and cannot be easily turned back, as the White House’s recommendation for U.S. commercial airlines to abide by China’s ADIZ regulations recognizes. Second, the way in which China has framed the issue suggests a deliberate effort to convince the United States that its interests are not aligned with Japan’s. The U.S.-Japan alliance is key to the U.S. rebalancing toward Asia, and many Chinese analysts have long seen this policy as little more than a prelude to—or a façade for—containment, or at least as destabilizing East Asia (Xinhua, November 26; “Pivot and Parry: China’s Response to America’s New Defense Strategy,” China Brief, March 15, 2012).

Beijing’s arguments rely on Washington’s privileging Sino-U.S. cooperation on a range of global issues above other commitments. As it has been presented, Japan appears to join a set of issues—including Taiwan and export controls—that Beijing claims inhibit progress in the Sino-American relationship. The framework that Beijing has put forward for reconciling problems in U.S.-China Relations—the “New Type of Great Power Relations” or “New Model of Relations among Major Countries” (xinxing daguo guanxi)—reinforces this kind of thinking, because it speaks to the long-held hope of a partnership and avoiding the pessimistic repetition of great power conflict (“Chinese Dreams: An Ideological Bulwark, Not a Framework for Sino-American Relations,” China Brief, June 7; “China’s Search for a ‘New Type of Great Power Relationship’,” China Brief, September 7, 2012). Yet, Beijing’s behavior in the South and East China Seas suggests this hope will come at the cost of acceding to Chinese pressure on the international system. Thus, the choice is not between U.S. relations with China or countries on its periphery, but rather between a partnership with China and preserving the international system Washington created.

Notes:

- Paul H.B. Godwin and Alice L. Miller, China’s Forbearance Has Limits: Chinese Threat and Retaliation Signalling and Its Implications for Sino-U.S. Confrontation, China Strategic Perspectives, No. 6 (Washington, DC: National Defense University, 2013) <https://www.isn.ethz.ch/Digital-Library/Publications/Detail/?ots591=0c54e3b3-1e9c-be1e-2c24-a6a8c7060233&lng=en&id=166508>