AirSea Battle and ADIZ: A Reaction to a Reaction

Publication: China Brief Volume: 13 Issue: 24

By:

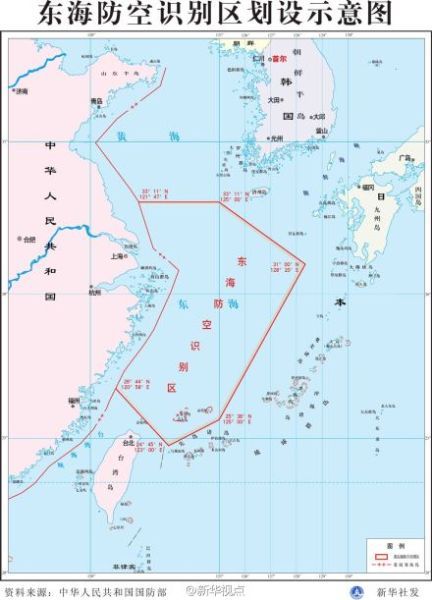

On November 23, China announced the creation of a new Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) covering the East China Sea. Immediate reactions have focused on its effect on the territorial claims of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. However, the new ADIZ is also a major step toward China’s ambitions to monitor and restrict foreign military activity in what it describes as its “Near Seas.” As Peter Mattis writes in this issue of China Brief, the rollout of the new zone displays no signs of crisis language, but instead appears to be the result of a careful policy process—likely a long-term effort to neutralize U.S. efforts to ensure access to the East China Sea, themselves a reaction to previous Chinese actions.

The ADIZ belongs not only to the context of China’s territorial disputes, but also to an escalating, if low-key, disagreement with the United States over operations in the Near Seas. It provides a legal framework for China’s complaints about U.S. intelligence-gathering flights near China’s borders, and for radar tracking and harassment of aircraft that fail to report flight plans to Chinese authorities—what Ministry of Defense (MoD) spokesman Yang Yujun described as “potential air threats” (MoD website, November 23).

In Chinese analysis, these efforts are necessary to resist growing threats from the U.S. military against the integrity of Chinese borders. The ADIZ is thus likely a response not only to Japan’s “nationalization” of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, but to the U.S. operational concept dubbed “Air-Sea Battle” (ASB) highlighted in Chinese analysis as proof of the threat of possible U.S. military intervention in China’s interests. ASB is itself a reaction to China’s earlier efforts to develop Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capabilities, suggesting that Chinese and U.S. military planners are already engaged in a conceptual arms race to produce frameworks for controlling access to the Near Seas.

While China’s military capabilities are growing they pale in comparison to those of the United States. Clearly aware of this, Beijing has developed a strategic posture that places its forces in position to wage an asymmetric struggle instead. Referred to as counter-intervention operations by Chinese scholars, or A2/AD by American strategists, PLA forces would attempt to exact vicious losses using ballistic and cruise missiles, ultra-quiet conventional submarines, advanced mines, possibly UAVs, and other weapons that are sophisticated and increasingly home-grown. Having studied the lessons of past military campaigns waged by Washington over the last several decades, Beijing sees strategic suicide in allowing a larger power the military advantage of building-up forces and then striking in mass. Halting such a build-up through an A2/AD strategy—with many Chinese scholars arguing for massive preemptive strikes—seems the best strategy if conflict ever occurred. [1]

In response to growing A2/AD challenges around the world, the United States has developed the operational concept of Air-Sea Battle. Holding a similar title to the NATO concept of AirLand Battle of the 1980s, ASB, in very broad terms, seeks to create a higher level of “jointness” between American air and sea power to overcome the challenge of A2/AD environments. At a recent public hearing of the House Armed Services Committee’s Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee, Rear Admiral James G. Foggo defined the concept as it stands today:

Such an operational concept is clearly aimed at negating China’s A2/AD capabilities, although almost all official ASB-related documents from the U.S. military take pains to avoid naming China specifically. This version of ASB implies the possibility of strikes on Mainland China to cripple important A2/AD command and control (C2) and C4ISR systems that would drive Beijing’s A2/AD “system of systems” (The Diplomat, September 26). Understanding Beijing’s reaction to ASB is of importance for obvious reasons: China is increasingly concerned over the implications of ASB, its effectiveness against its growing military might and A2/AD strategy. Through a series of articles in mainstream Chinese media, comments by senior officials and most importantly possible acquisitions of new military technology from Russia that could help defend current and future ADIZ plans, Beijing has demonstrated a clear focus on the challenge presented by ASB. Indeed, China’s reaction to the concept will have clear ramifications for the security situation throughout the Indo-Pacific, for America’s allies, as well as for the various flashpoints throughout the region.

Reactions in the Press to AirSea Battle

An unsigned article in the People’s Daily titled, “AirSea Battle Renews Old Hostility,” argued, “If the U.S. takes the AirSea Battle system seriously, China has to upgrade its anti-access capabilities. China should have the ability to deter any external interference but unfortunately, such a reasonable stance is seen as a threat by the U.S.” The article goes on to note that:

Chinese officials have also commented in various formats dismissing the ambiguity of American defense officials to name ASB as being specifically aimed at China. Speaking to the Financial Times, Li Yan, a researcher at the Chinese Institutes of Contemporary International Relations notes that “even if you say it’s not completely aimed at China, it is still mainly aimed at China.” He went on to explain that “For the Americans have said very clearly that AirSea Battle is mainly directed at anti-access and area denial warfare, and [past U.S. assessments] all show that they believe China is conducting anti-access and area denial warfare” (Financial Times, December 8, 2011).

While one must take seriously Chinese statements concerning ASB, scholars must also look for changes in Beijing’s actions, specifically, changes in military tactics, strategy and/or procurement. As noted above, China may seek to enhance its A2/AD capabilities to offset the power of ASB. Indeed, recent reports suggest Beijing may be close to signing various deals with Russia in hopes of enhancing its own A2/AD and conventional military capabilities.

Striking at ASB Through New Defense Technology

One such agreement that has been in and out of the news in recent years is China’s possible acquisition of the SU-35 fighter. While the deal is by no means sure, it is an indication of China’s military desires (see China Brief, October 10). . If acquired, the SU-35 would give China the ability to deploy advanced fighter jets for longer periods of time in the East and South China Seas, improving the effectiveness of patrols in the new ADIZ. The aircraft would also likely be superior to most fighters in Asia (minus the F-22 or later F-35) and fill the gap until presumably domestic 5th generation stealth airframes can come on line like the much-discussed J-20.

Beijing may also be interested in acquiring a new generation of ultra-quiet submarines from Moscow (Want China Times, September 9; South China Morning Post, March 25). This has been tied to press reports surrounding a possibly SU-35 sale in many instances. While reports do vary on the firmness of any deal, an infusion of new submarines would be of vital importance to China not only for the ability to deploy undersea vessels with greater capabilities but also new technologies each sub would come with (Russian AIP engines, quieting technologies etc.). Such technologies could give future Chinese boats new capabilities over time that would help negate the large advantage American and allied forces have in anti-submarine warfare that could be part of an ASB-based strategy.

Reports have also surfaced that Russia may even consider selling to China its most prized air defense system, the much discussed S-400 (Voice of Russia, May 6, 2012). Such a sale would have clear ramifications if such systems were deployed across the Taiwan Strait and near the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku islands. In its article detailing the possible sale, Defense News notes that such a sale will give Beijing “complete air defense coverage of Taiwan” and allow for important “ballistic-missile defense capabilities that it lacks” (Defense News, May 25). Such a system would also certainly raise the level of risk U.S. and allied forces would face if kinetic strikes on the Mainland were part of an ASB strategy. If deployed in the area of the East China Sea, such new air defense technology would also assist in giving teeth to China’s new ADIZ.

While China may clearly be exploring its options to increase the utility of its A2/AD capabilities against a future ASB-based strategy via Russian weapons sales, there are clear challenges to such a strategy. First, even if Beijing were to purchase all of the above weapons systems, Chinese planners would need ample time to learn the intricacies of such systems, adapt them to their own needs, tie them into China’s own command and control systems as well as achieve a high level of competency in training to be able to fight under war-time conditions—certainly not something that can be done quickly.

History also suggests that Moscow may balk at such agreements. Russia has not forgotten the case of the SU-27 fighter sold to China in 1992 and in time expanded to allow Beijing to build the aircraft domestically. The agreement broke down when Russia accused China of copying the plane and recasting it for sale on the global arms market. However, given warming relations, increased military cooperation and joint training as well as converging goals of negating American power, Moscow may see increasing utility in selling such weapons to Beijing.

The dueling strategic doctrines of Beijing and Washington will have ramifications not only for both parties but the entire Asia-Pacific and wider Indo-Pacific. A trend of precarious security competition—recently highlighted by China’s ADIZ declaration—is in danger of now becoming what many political scientists like to term a “security dilemma.” With America attempting to negate China’s A2/AD strategy with ASB and Beijing looking for responses to ASBChina is likely to take more steps like the establishment of the East China Sea ADIZ, worsening the risks of miscalculation and conflict (The Diplomat, December 4).

While both sides clearly seek strategic advantage over the other, both parties must recognize continued dialogue and cooperation on various fronts can at least hope to mitigate some strategic tensions. China’s creation of an ADIZ in the East China has been interpreted by many as a hostile act driven by territorial disputes. The move, however, must also be seen in the context of growing Sino-U.S. security competition involving new military platforms, operational concepts and strategies–a conceptual arms race to produce frameworks for accessing and controlling parts of the global commons in maritime Asia.

What the future holds for this region may be decided not only by how each side responds to one another’s strategic maneuvers, but if both sides are serious at looking for ways to reduce tensions. If not, a toxic pattern of move and counter-move could be the new norm—with dangerous ramifications for years to come.

Notes:

- See Jiang Lei, Modern Strategy for Using the Inferior to Defeat the Superior, Beijing: National Defense University Press, 1997, and Shen Kuiguan, “Dialectics of Defeating the Superior with the Inferior,” in Chinese Views of Future Warfare, Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 1998.