China’s Ideological ‘Soft War’: Offense is the Best Defense

Publication: China Brief Volume: 14 Issue: 4

By:

Beijing regularly reminds us that its foreign policy eschews the export of ideology and meddling in the political affairs of other countries. According to its concept of “peaceful development,” China has no intention of exporting ideology or seeking world hegemony, nor does it seek to change or subvert the current international order. In the same breath, Beijing frequently chides the United States as a serial offender in exporting ideology to shore up its international hegemony as the world’s dominant superpower.

China sees itself as the target of powerful Western political, military and media efforts to pursue neoliberal strategies of ideological world dominance.

Beijing thus purports to maintain a defensive posture in relation to the export of ideology by other actors and the United States in particular. It articulates this in terms of safeguarding its “ideological security” against “ideological and cultural infiltration.”

Beijing characterizes its strategic intentions as mainly “inward-looking” while the United States’ are “outward-looking.” Thus, their strategic intentions do not clash (China Daily, September 9, 2013). While this inward versus outward characterisation appears prima facie to suggest a non-competitive arrangement, reality suggests otherwise. In addition to its defensive ideological posture—and as much as Beijing might state otherwise—there is an “outward-looking” element to this posture. While there exists no evidence that Beijing is exporting ideology for the purpose of universalizing its political values, there is evidence that it is doing so to safeguard its own ideological security in the face of a US-led “soft war.”

By examining Chinese discourse on the subject, this paper examines the extent to which Beijing is exporting its ideology to shore up support abroad, most notably among non-Western developing nations. To this end, it will be shown that Beijing is maneuvering to put its worldview forward as an alternative to the ideological hegemony of the West.

Defending Against Ideological Infiltration

“Exporting ideology” is used as a pejorative term by Beijing to refer to a state or non-state actor attempting to indoctrinate a country’s government and/or people. The Chinese concept of the export of ideology (shuchuyishixingtai (v.); yishixingtaishuchu (n.)) incorporates notions of hegemony, homogenization and universalism. Beijing conceptualizes “exporting ideology” as a universalizing endeavor in which a state or non-state actor seeks to globalize their ideology by replacing all others.

Thus, it associates Western neoliberalism and religious fundamentalism (such as wahhabi Islamism) with the export of ideology, demonstrated in recent times by such phenomena as the “color” revolutions, the spread of jihadist violence and the erosion of indigenous cultural values. Western neo-liberalism is described by Chinese political commentator Fu Yong as a form of “postmodern imperialism,” in which the objective is neither land, resources nor direct political control, but rather ideological dominance (Global View, June 2006).

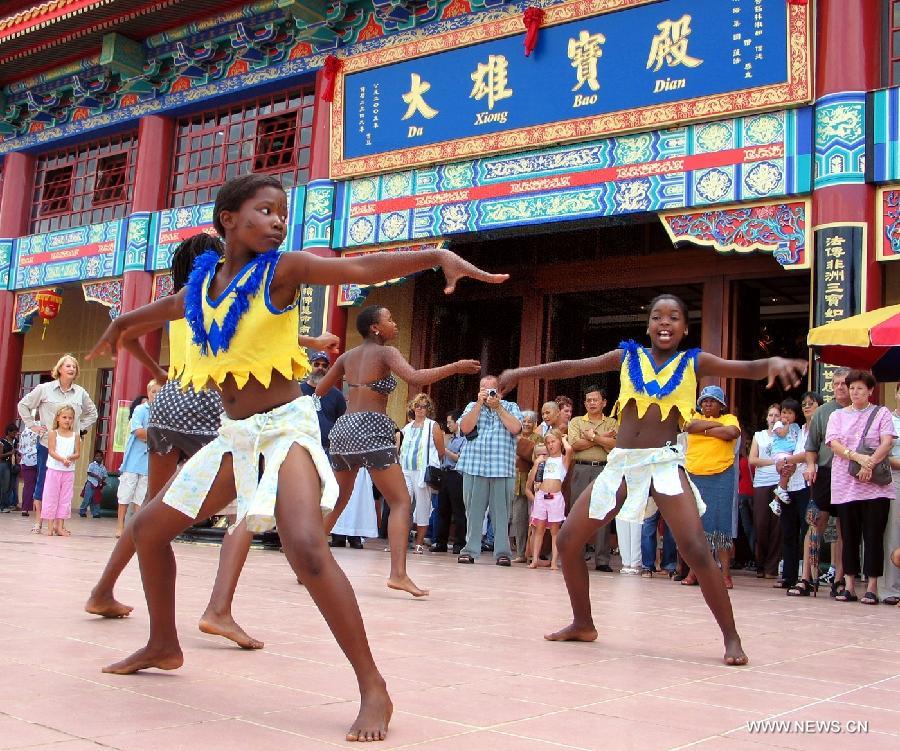

China, we are told, does not export ideology but rather promotes its culture and economic cooperation overseas, seeking greater understanding and acceptance with the goal of a multipolar and ideologically heterogeneous world. It is a line regularly invoked in relation to China’s development assistance and trade cooperation with Africa. In relation to its relations with Africa, veteran Chinese diplomat Liu Guijin, states that Beijing “strictly follows the principle of equality and mutual benefit.” Its dealings with the continent are not for the “export of ideology and development mode, not to impose its own social system, not to attach political strings… nor to seek privileges or a ‘sphere of influence’ ” (address given at the 2010 China-Africa Economic Cooperation Seminar).

Accordingly, socialist countries, including China, are depicted as victims or targets—not perpetrators—of ideological export. China’s experience of receiving ideological export is thus articulated in terms of “ideological infiltration” or “ideological and cultural infiltration” (sixiang/wenhua shentou). China, for example, has been the target of ideological infiltration by wahhabi Islamic doctrine in the troublesome autonomous region of Xinjiang. China’s people have as a whole have been victims of infiltration by the Western values of money worship, hedonism and extreme individualism and, in North Korea, Western imperialist ideological and cultural infiltration is reported to be “more vicious than ever” (China.com, September 2, 2013).

Cheng Enfu, head of the Institute of Marxism at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, notes that, the infiltration of American ideology and values into other countries has accelerated with globalization and technology, with ideological security (yishixingtai anquan) facing increasingly severe challenges from information networks (Global Times, June 3, 2013). In acknowledgment of this, national ideological security has been elevated as a policy imperative under Xi Jinping. Listing “cultural threats” among its five focuses, China’s new National Security Committee, announced after the Party’s third plenum in November, is the latest in a string of initiatives to shore up ideological security. Colonel Gong Fangbin, a professor at the National Defense University, pinpoints “the ideological challenges to culture posed by Western nations” as a target of the committee (South China Morning Post, January 14).

Surviving Cold War 2.0—a ‘Soft War’

The Global Financial Crisis is seen by a number of Chinese theorists as emblematic of the declining economic power of the West relative to China and BRICS economies. This decline has precipitated a shift in European and US foreign strategy away from economics to a greater reliance on soft power and a strengthening of ideological exports (Guangming Daily, June 27, 2013).

China thus finds itself thrust into an era of ideological “soft war” (ruanzhan). Unlike a hot, cold or hard war, a soft war is a contest of soft power in which the purpose of each state is to “protect its own national interests, image and status so as to promote a stable international environment conducive to its development” (Liberation Daily, May 10, 2010). In the soft war era, states Zhao Jin, Associate Professor at Tsinghua University’s Institute of International Studies, international relations is no longer a hard power scenario in which “might is right,” but where “morality” and “justification” become the basis of relative state power (Liberation Daily, April 23, 2010).

Originally used by Iranian authorities following the disputed presidential election of 2009, the term “soft war” referred to a climate of opposition that forced the government to crack down on dissent though media controls and propaganda campaigns. Robert Worth, writing for the New York Times (November 24, 2009), comments that the term is “rooted in an old accusation [by Iran’s leaders]: that Iran’s domestic ills are the result of Western cultural subversion.” The alleged strategy of soft war, writes University of Pennsylvania professor Munroe Price, “is one of encouraging internal disintegration of support for the government by undermining the value system central to national identity” (CGCS Mediawire, October 22, 2012). It undermines a society’s values, beliefs and identity to “force the system to disintegrate from within.”

Price notes that broadcasters in the West often point to the collapse of the Soviet bloc as a triumphant example of the use of media in “altering opinion and softly preparing a target society to become a more intense demander of democratic change” (International Journal of Communication, 6, 2012). Although a desirable model in the West, it is regarded a cautionary tale in Beijing, an example of the West’s strategy of “peaceful evolution” (heping yanbian). Formulated during the Cold War by former US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, the strategy pursued “peaceful” transitions from dictatorship to democracy in communist countries. Researchers in China have assessed that the fundamental reason for the collapse of the Soviet Union was a lack of cultural construction, leaving the socialist system without a bulwark against the West’s strategy of peaceful evolution (Zhang Ji, Qi Chang’an, Socialism Studies 6, 2003).

Thus, the production of culture in China remains firmly controlled by the Party. Within China’s domestic political discourse, the terms “ideology” and “culture” are often used together and often interchangeably, and responsibility is placed on the media and cultural workers to correctly guide public thinking. Dissent, as we have seen with Beijing’s recent crackdowns on rogue journalism and internet rumors, continues to be stifled (for more on the recent crackdowns, see “The Securitization of Social Media in China” in China Brief, February 7). The continuing development of the culture industry to promote ideology and to project China’s soft power both at home and abroad is thus intended “to ensure cultural security as well as the nation-state’s image.” [1]

Shaping a Favorable International Environment: Culture on the Offensive

Delivering a speech at a group study session of members of the Political Bureau of the Party’s Central Committee on 30 December 2013, president Xi Jinping called for deeper reform of China’s cultural system in order to build a solid foundation for the nation’s cultural soft power (wenhua ruanshili) (Xinhua, January 1). Xi said that “the stories of China should be well told, voices of China well spread and characteristics of China well explained.”

Beijing’s international cultural charm offensive is, according to official pronouncements, about making China understood so as to minimize uninformed misgivings over China’s rise among international audiences. The objective is perhaps nowhere more clearly articulated than by Minister for Culture, Cai Wu, when addressing Xinhua reporters during an August 2010 interview:

We aim to carry out cultural exchanges with China not to export ideology and mode of development , but through the dissemination of Chinese culture, so our culture can be truly attractive, to impress people, resonate , strike a chord , win respect , enhance communication of the mind, and seek understanding and cooperation so that the outside world gains a comprehensive, accurate understanding of the true face of contemporary China; thereby creating a more favorable international environment for our modernization (Xinhua, August 6, 2010).

But there is clearly a range of views about the role that the international promotion of culture should play in Chinese strategy. In his 1998 Analysis of China’s National Interests, which won the China Book Prize, Tsinghua University’s Yan Xuetong observes that “exporting ideology is a major part of promoting Chinese culture. It is also an important way to raise China’s international status.” According to Yan, whose views are purported to closely reflect those of Beijing, China’s quest to enhance its status and the United States’ efforts to maintain its current position is a “zero-sum game.” It is the battle for people’s hearts and minds that will determine who ultimately prevails, and that the country that displays the most “humane authority” will win.

Yan’s zero-sum game echoes the characterization of the soft war era put forward by his junior Tsinghua University colleague Zhao Jin, in which “morality” and “justification” become the basis for a state’s relative power. In this sense, we see a link between moral authority and soft power: the more widespread the acceptance of a state’s moral authority within the international system, the greater its soft power. The logic of commanding the international moral high ground within a soft war era thus requires that a state achieve moral authority among a more dominant collection of states than do its competitors.

The “favorable international environment” in which Beijing seeks to pursue China’s development is one that requires claiming this high ground, allowing China to rise unencumbered by an international moral consensus dominated by the West. It has required a posture that—despite Beijing’s foreign policy rhetoric—is outward looking. It necessitates the recruiting of partners to Beijing’s way of thinking and away from the West’s. It requires—and results in—the projection of its ideology beyond its borders. Thus, China exports its ideology to markets around the world in direct and targeted competition with Western ideological exports, competition that is being played out most intensively in regions such as Africa, Central Asia and Latin America.

Conclusion

China purports to seek an ideologically heterogeneous world in which differences are respected and ideologies peacefully coexist. It does this in part via its projection of cultural soft power, which ostensibly promotes Chinese culture in pursuit of understanding and a favorable international environment in which to pursue its national interests.

Facing a soft war scenario in which US-led Western ideological infiltration poses an enduring existential threat to the socialist Chinese state, Beijing finds itself locked in a zero-sum soft conflict with the United States. Beijing must therefore thwart Western ideological hegemony within the international system in order to create for itself the favorable international environment it seeks. It does—and will continue to do—so by seeking to “contain” the global ideological footprint of the West within its geographic footprint, and to expand its own.

Neoliberal ideology will thus continue to be seen as an enemy of the Chinese state, in terms of its infiltration both of China and of the non-Western world. China’s efforts will focus on (i) pursuing agenda-setting strategies aimed at the West in order to break the perceived dominance of neoliberalism within Western political discourse, media and cultural production; and (ii) defending the non-West against the export of ideology by the West by continuing to cultivate support for Chinese culture and ideology in the developing world. China’s soft war is thus a battle on two fronts: domestically in defense against foreign ideological infiltration, and externally in its export of ideology.

Notes

- Jiang Fei and Huang Kuo, “Transnational Media Corporations and National Culture as a Security Concern in China,” in V. Bajc and W. de Lint (Eds.), Security and Everyday Life. Routledge (2011).