China’s New Leaders to Strengthen the Party-State

Publication: China Brief Volume: 12 Issue: 23

By:

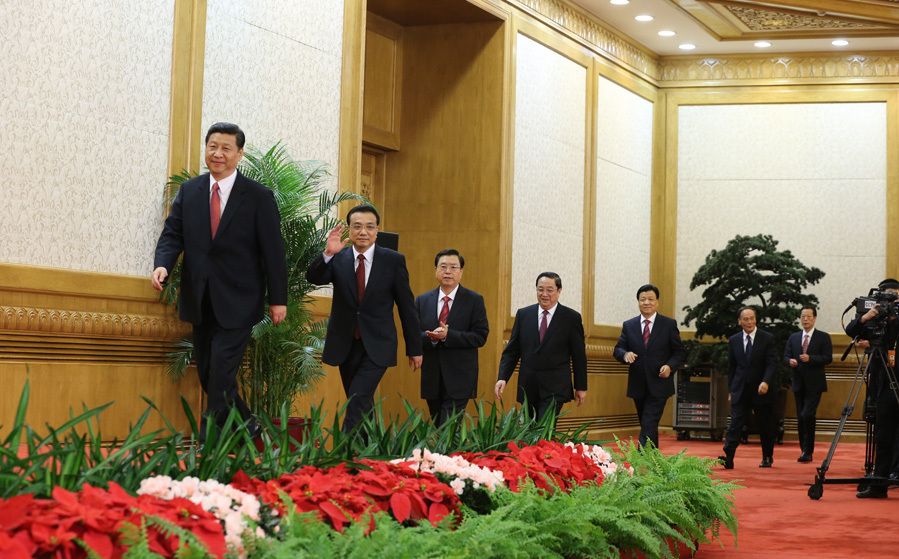

The rightward-shift in China’s politics was institutionalized formally at the highest level on November 15 when Xi Jinping became the new general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Right-leaning leaders dominate the new seven-member Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC). In addition to Xi, they include four others holding key posts in the party and government (see Table). The only voices of the left in the new leadership are Premier-designate Li Keqiang and propaganda czar Liu Yunshan, both products of the Communist Youth League system. The new right-leaning leadership is composed primarily of those like Xi who in their policy leanings emphasize law and order, the developmental state and expanding China’s international power. The era of Bismarck has dawned in China.

|

Table 1. |

||

|

Name |

Position |

Faction |

|

Xi Jinping |

General Secretary |

Leninist Nationalist |

|

Li Keqiang |

Premier |

Marxist Romantic |

|

Zhang Dejiang |

NPC Chairman |

Leninist Nationalist |

|

Yu Zhengsheng |

CPPCC Chairman |

Leninist Nationalist |

|

Liu Yunshan |

Propaganda Director |

Marxist Romantic |

|

Wang Qishan |

CDIC Chairman |

Leninist Nationalist |

|

Zhang Gaoli |

Executive Vice Premier |

Leninist Nationalist |

While it easy to overemphasize the importance of the leadership transition, several changes are notable. The return to a seven-member Politburo Standing Committee following the nine-member committee that resulted from a political standoff in the 2002 succession will make things easier for Xi. As stated in a previous article, since Xi does not enjoy the imprimatur of influential CCP “elders” (yuanlao), his position would be precarious if he took over a divided PBSC (“The Politics and Policy of Leadership Succession,” China Brief, January 20). The shrinking of the body back down to seven had the effect of giving him a five to two advantage over the left-leaning forces—two of whose members, Wang Yang and Li Yuanchao, were squeezed out of the competition. Moreover, Xia’s two closest allies—Wang Qishan, previously vice premier in charge of trade and finance, and Zhang Dejiang, previously vice premier in charge of energy, transportation and industry—both made it in. Xi will be more in control with five out of seven seats compared to five out of nine.

The other notable change is the emphasis placed on law and order. Wang, who is best known for his work on economic policy, was made head of the party anti-corruption watchdog, suggesting Xi intends to oversee this area personally. In both his “meet the press” speech and in his first speech issued three days later, Xi put special emphasis on the dangers posed to the party by corruption. Unusually, he even made a veiled reference to the overthrow of authoritarian regimes in the Middle East in the latter speech: “In recent years, as a result of the accumulation of problems, a number of countries have experienced popular anger, street protests, social unrest, and regime collapse. Corruption was among the most important of the reasons.” Xi said the party was in danger of developing rickets from “calcium deficiency” if it did not rebuild its principles from the inside (Southern Daily, November 19). This extraordinary admission that the CCP may have lost any historical legitimacy or special claim and is today no different from standard-issue authoritarian regimes signaled both how Xi thinks of the party and how far the party has come.

The release of the speech on November 18, just three days after his selection, signaled that Xi is far more in charge during his leadership transition than was Hu, whose first major speech was not released for nearly a month after his selection in 2002 and who all but disappeared from public view during that time. In the same vein, Xi’s takeover of the party’s Central Military Commission also was indicative of his strong succession. Hu, by contrast, waited nearly two years for the military succession. Hu made sure he was the one to strut across China’s first aircraft carrier, Liaoning, in September and to lay claim at the congress to being the father of China’s rising status as a “maritime power.” Xi quickly asserted himself, however, as the leader of China’s growing military by issuing a eulogy and commendation for the chief designer of China’s carrier-borne aircraft program, Luo Yang, who died of a heart attack while organizing the first landings of aircraft on the Liaoning from 18 to 25 November (Xinhua, November 27). Official media jumped in to declare Luo as “the new Qian Xuesen”, referring to the father of China’s atomic bomb (Global Times, November 27). The suggestion is clear: China is entering a new era of global assertiveness under Xi who, like Mao, will “stand up” to the world.

Still, while the Xi era, not the Xi-Li era, is undoubtedly dawning, the term limits of all CCP heads now have been established firmly. Xi made no attempt to praise the policies of Hu in his cluster of opening speeches, showing he intends to take the country in a new direction if he can. The urgency of acting quickly, however, is underscored by the notion that his successors in 2022—if the CCP survives until then—will likewise feel no compulsion to follow his lead. As befits the open-ended nature of the 2022 succession, one 49-year old from the right-side, Sun Zhengcai, and one from the left-side, Hu Chunhua, joined the Politburo as regular members. The future is up for grabs even if the present surely belongs to Xi.

Policy Implications

In retrospect, the CCP was extraordinarily successful this political season in inculcating a sense of excitement and anticipation about its new leadership among overseas scholars, analysts and journalists. A more effective propaganda campaign is hard to imagine. Breathless commentary and eager curtain-raisers filled the media and policy journals prior to the congress. Looking back on the Hu Jintao era, however, provides a welcome corrective. In fact, the leadership transition is not that important except for what it tells us about the forces shaping Chinese politics and policy. The Xi leadership, as with the Hu-Wen leadership before it, is more a consequence than a cause of China’s politics and policy.

What are those forces? The main policy divisions in China today pit the right-leaning “Leninist Nationalists” who want a strong, nationalist state with a bare-knuckled market economy against the left-leaning “Marxist Romantics” who want a just and redistributive state. The Leninist Nationalists moved up through technocratic positions in government, usually in wealthy coastal areas, and care most about national power and party discipline. The Marxist Romantics usually earned their spurs within party organizations and in poor inland areas, and they care most about social equity and party ideology (“The Politics and Policy of Leadership Succession,” China Brief, January 20). Despite widespread claims, the high-profile party chief of Chongqing Bo Xilai, whose fall before the congress might have made it easier for Xi to shrink the PBSC to seven, was a classic Leninist Nationalist. His embrace of Maoist symbolism merely underscored how Mao has increasingly become a hero of the angry, nationalist right in China rather than of the downtrodden, romantic left.

Xi’s initial speeches harped on the main themes of the Leninist Nationalists: economic growth, the middle class, party corruption and national greatness. There were few words about inequality, ideology, fairness or justice. With five of seven PBSC seats under his command, the main implication of the leadership transition for policy is that the Leninist Nationalist vision will face few if any constraints within the party. The main limitations, rather, will be external: whether China’s people and its economy respond positively to the policy prescriptions of this group.

What should we expect in terms of immediate policy decisions? One implication is that liberalizing political reforms are off the table. The Leninist Nationalists want to rebuild party and state power, not disperse it. For the last ten years, for instance, there has been a vigorous debate within the party about an experiment in a separation of government functions into decision-making, administration and supervision in Shenzhen known as “administrative trifurcation” (xingzheng sanfenzhi) [1]. Although the Leninist Nationalists have managed to prevent the model from spreading, it is now almost certain that the experiment will be buried once and for all. Narrower administrative reforms such as the retiring of regulations through an “administration examination and approval” (xingzheng shenpi) reform committee within the State Council also may be slowed.

Another implication is that the attempts by outgoing Premier Wen Jiabao and Hu to revitalize rural China through an expansion of peasant property rights, an end to limits on internal migration and a shift of state welfare spending to rural areas will face stiff resistance. Instead, the pro-growth Leninist Nationalists will take their cues more from the developmental dictators of Asia’s past such as Park Chung-hee, the military general whose rule in South Korea from 1963 to 1979 is credited with spurring that country’s miracle. Park, whose daughter may become South Korea’s new president in December, is the subject of fascination in policy circles in China [2]. For many, China should embrace the sort of right-wing developmental dictatorship that Park represents. Under Xi, such views will get a stronger hearing.

Finally, when it comes to technocratic policy issues in areas like energy, economics, trade and the environment, Xi could achieve greater progress than his predecessors given his stress on growth and government efficiency. A draft Climate Change law issued in March, for instance, suggests China will focus on technology and renewable energy development at the center of its plans. Carbon taxes are unlikely, and a national emissions trading scheme will not launch until 2016 at the earliest. Given massive subsidization of renewable energy and energy-saving technology, the Xi administration, however, could bend China’s soaring greenhouse gas emissions trend line down. Doing so will depend in part on rebuilding state capacity—something the Leninist Nationalists will consider their top priority.

Notes:

-

See, for example, Hu Bing, “Xingzheng sanfenzhi: zhidu beijing fenxi [Adminstrative Trifurcation: A Background Analysis],” Hubei shehui kexue [Hubei Social Sciences], 2004, pp. 14–17; and Yu Liuning, “Woguo xingzheng tizhi gaigede xin tujing—xingzheng sanfen zhi [Administrative Trifurcation: A New Breakthrough in Administrative Reforms in China],” Qiye daobao [Enterprise Herald], 2012, pp. 19–20.

-

See, for example, Hao Honggui, “Pu zhengxi jiquan tongzhi yu hanguode zhengzhi xiandai hua [Park Chung-hee’s Concentrated Control and the Political Modernization of South Korea],” Tansuo yu zhengming [Exploration and Views], No. 12, 2008, pp. 72–75.