China’s Sinking Port Plans in Bangladesh

Publication: China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 10

By:

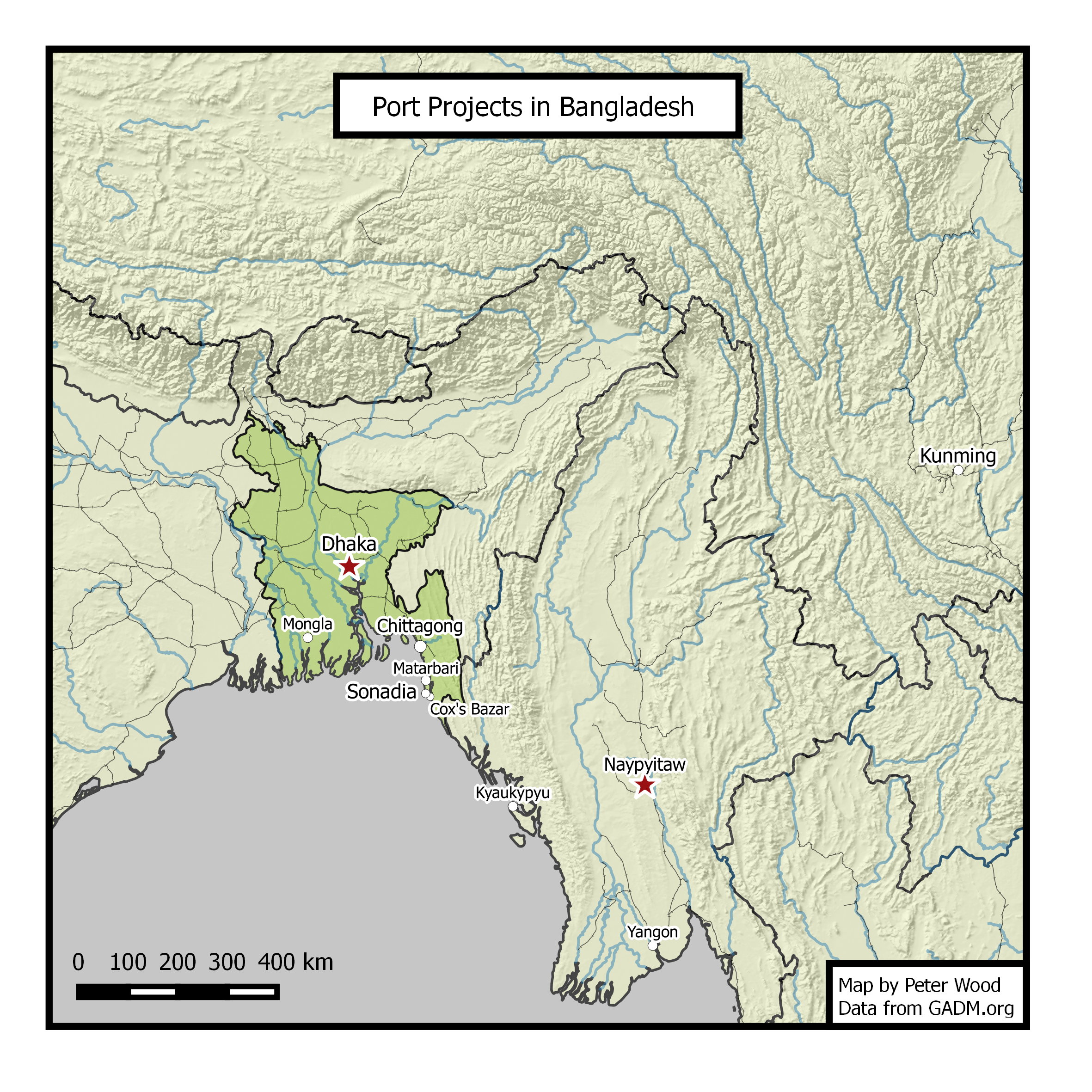

A key link in China’s Maritime Silk Road (MSR) suffered a setback in February when Bangladesh’s Awami League (AL) government shelved plans for construction of a deep-sea port at Sonadia, south of Chittagong. Bangladesh is an important participant in China’s “One-Belt, One-Road” (OBOR) initiative. An Indian Ocean littoral state, it figures in the OBOR’s overland links (via the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar [BCIM] corridor) as well as maritime components. China was hoping to design, build and operate the port at Sonadia, which was expected to emerge an important transshipment hub for the MSR (Daily Observer, September 12, 2015). It would have been an alternative to the deep-sea port at Kyaukpyu that Beijing is building to link its underdeveloped southern provinces to the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. It would have further eased its dependence on the sea routes transiting the Straits of Malacca.

The port at Sonadia would have been Bangladesh’s first deep-sea port. The Bangladeshi government has been keen to build a deep-sea port in the country as its existing ports at Chittagong and Mongla have a shallow draft, are heavily congested and inadequate to meet the mounting needs of its growing economy, which is reliant on sea-borne trade. When the idea of building a new deep-sea port at Sonadia was first conceived in 2006, it was seen as a way to not only overcome the limitations of the Chittagong and Mongla ports but also to transform Bangladesh into a maritime transshipment hub for landlocked Nepal, Bhutan, India’s Northeastern states and China’s Yunnan province (Daily Star, March 20, 2013, Bdnews24.com, June 8, 2014 and Bdnews24.com, June 4).

When Bangladesh sought China’s help to build a deep-sea port at Sonadia, the latter responded positively (Daily Star, October 25, 2010). It submitted a detailed project proposal and agreed to provide loans to cover a major part of the project cost (Daily Star, January 23, 2012 and Bdnews24.com, June 8, 2014). Other countries, including the United Arab Emirates and Netherlands submitted proposals too, but these proved less attractive to Bangladeshi decision makers (Prothom Alo, June 4, 2014). According to former Ambassador and Secretary in Bangladesh’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Humayun Kabir, China’s experience in implementing several mega infrastructure projects in Bangladesh over the past 30 years and proven expertise in construction of deep-sea ports in the region, demonstrated that it could “provide technology, funds and expertise at a competitive rate.” [1] All of these elements worked in China’s favor, and Bangladesh was set to award the contract to the state-owned China Harbor Engineering Company Ltd (Prothom Alo, June 4, 2014). The two sides unexpectedly failed to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) during Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s visit to Beijing in July 2014. A few months later Bangladesh’s Minister for Planning Mostafa Kamal said that the government was reconsidering the project (Dhaka Tribune, January 11, 2015). The final blow came in February when Bangladesh called off the project (Times of India, February 8).

The Decision to Cancel

So why did Bangladesh cancel the Sonadia project? In 2014, Japan came up with a proposal for a project at Matarbari, 25 km from Sonadia, which would include not only a deep-seat port but four coal-fired power plants and an LNG terminal. It offered to provide 80 percent of the funding for the $4.6 billion port on easy terms. Building two ports just a few kilometers apart was seen as economically unviable, and as Japan’s terms were more favorable, the Bangladesh government chose the Matarbari project and scrapped a port at Sonadia (Dhaka Tribune, January 11, 2015 and Daily Observer, September 12, 2015).

Geopolitics played a role too. India, Japan and the U.S., which are wary of China’s growing presence in the Indian Ocean, are reported to have pressured the Bangladesh government to cancel the Sonadia project (Asian Age, February 10). The latter was unable to resist such pressure. India had “stood behind” the AL government in 2014 on the issue of the “questionable general elections” that returned it to power and in the circumstances, the latter did not want to “displease” India, the former ambassador observed. [2] Commenting on the AL government’s vulnerability to pressure from the U.S., a retired Indian Military Intelligence specialist on South Asia pointed out that the U.S. played “a major role in bringing back Sheikh Hasina to power” and she has “a big stake in the U.S.’ continued support for her.” This and the fact that the U.S. is Bangladesh’s largest market for readymade garments, its largest earner of foreign exchange, appears to have prompted the government to shelve the Chinese project. [3]

Setback for China

Sino-Bangladesh co-operation has deepened over the decades. The two countries now share a robust military relationship. Bangladesh is China’s second largest weapons market (after Pakistan) and China is Bangladesh’s largest supplier of military equipment, accounting for 82 percent of all of Dhaka’s weapons purchases between 2009 and 2013 (Dhaka Tribune, March 18, 2014). China is also Bangladesh’s largest trading partner; two-way trade was worth $12 billion in 2014 (Daily Star, October 2, 2015). Chinese investment in Bangladesh has grown significantly in recent years. Between 1977 and 2010, Beijing’s investment in Bangladesh amounted to just $250 million compared to roughly $200 million in 2011 alone (Daily Star, September 21, 2012). Investment has surged since with China pledging billions of dollars in investment in garment factories in special economic zones, infrastructure building, etc (Click Ittefaq, September 30, 2015).

China’s role in infrastructure building in Bangladesh is significant and growing. It is upgrading Chittagong port and building road and railway links from Kunming in Yunnan province to Chittagong. It has undertaken financing and building of eight “friendship bridges,” including the Padma Multi-purpose Bridge, which is Bangladesh’s largest-ever infrastructure project, and a high-speed “chord” train line between Dhaka and Comilla (New Age, February 13, 2015; Daily Star, March 8, 2015 and Daily Star, October 2, 2015). Its work on the overland component of the OBOR in Bangladesh appears to be progressing well.

However, OBOR’s maritime component has run into difficulties. In addition to the shelving of the Sonadia port project, development of Matarbari port is being undertaken by Japan, China’s rival. Besides, the prospects of China alone being awarded the contract to build a planned port at Payra in Patuakhali district seem dim now. Since Payra is situated closer to the Indian mainland than is Sonadia, India’s opposition to a China-built port here can be expected to be fiercer. At best, China can expect to be part of a large group of countries developing this port (Times of India, February 8).

While China would be able to use these ports for trade, it will have to share use of these ports with other countries. This will be case with Chittagong and Mongla ports too; an MoU signed by India and Bangladesh last year allows Indian cargo ships access to these ports (Bangladesh, Ministry of Foreign Affairs).

A group of Indian analysts argue that China’s MSR strategy is just a more benignly packaged version of the U.S.-coined “string of pearls strategy.” (Nikkei Asian Review, April 29, 2015). In the context of Bangladesh, this would mean that military motivations and not economic interests underlie China’s interest in building and operating ports and that the ultimate goal is to use Bangladesh’s commercial ports as naval bases should the need arise. This goal would require China to design ports and to operate them. The shelving of the Sonadia projects denies China such a role. Importantly, it would require China to have immense influence over the Bangladesh government. Bangladesh’s recent decisions on port building that went against China indicate the latter’s waning influence.

The cancellation of the Sonadia port is a blow more to the MSR’s military goals, if any, than to its economic goals as the loss of Sonadia does not prevent China from using Bangladesh’s other ports or the deep-sea port at Kyaukpyu to link up Yunnan province. It only weakens the prospects of China finding ports in Bangladesh for military use.

Battles Ahead

The setback over the Sonadia project, though disappointing to China, is unlikely to deter it from seeking greater influence in Bangladesh through investments and participation in infrastructure projects, especially port-related ones. Imported oil, much of which is transported on ships via sea routes in the Indian Ocean, makes it imperative for China to establish close ties with Bay of Bengal littoral states, including Bangladesh. It can be expected to accelerate efforts to develop such ties. Already in 2015, it promised to invest $8.5 billion in 10 infrastructure projects (New Age, February 13, 2015).

However, it can expect its investment plans in Bangladesh to be challenged by other powers that are eyeing Bangladesh as an investment destination and to further their strategic interests. Japan, for one, which is Bangladesh’s largest aid donor and development partner, has pledged $6 billion in soft loans. As part of its Bay of Bengal Industrial Growth Belt (BIG-B) initiative, the centerpiece of its strategy in the region, Japan is developing an industrial agglomeration along the Dhaka-Chittagong-Cox’s Bazar belt that focuses on industry and trade, energy and transportation (South Asia Monitor, April 15). The Matarbari complex is part of this initiative. Japan’s wresting of the deep-sea port project from China signals Tokyo’s significant capacity to take on the Chinese in South Asia.

While Japan has the technical expertise and financial muscle to match, even better Chinese infrastructure project proposals, it is India’s influence in Bangladesh that is the major obstacle in the way of Beijing’s ambitions in the Bay of Bengal. When Bangladesh was under military rule and in the years that the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) was in power, India’s relations with Dhaka were under considerable strain. But with the AL at the helm since 2008 and especially after 2014, India’s relations with Bangladesh have improved remarkably (The Hindu, May 11, 2015). Indeed, Bangladesh is now “clearly tilted toward India; it influences major decisions,” the former ambassador observed. China wields only “moderate influence” in Bangladesh, in comparison, he said. [4] In the circumstances, it is unlikely that Bangladesh would go against Delhi to award projects to China, especially those that are seen to undermine India’s security interests.

Adding to China’s woes in Bangladesh is the growing convergence between India and the U.S., underscored recently in their agreeing in principle on a Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement, which will enable their militaries to use each other’s assets and bases for repair and replenishment of supplies and assumes importance as they seek to counter the growing maritime assertiveness of China (The Hindu, April 18). On issues in India’s neighborhood, the U.S. is “silently recognizing these countries as areas of India’s strategic influence,” the military intelligence specialist said, adding that this is “probably worrying” China. [5] This means that India’s hand in Bangladesh will be strengthened by US backing.

However, China’s recent setbacks in Bangladesh—besides the shelving of the Sonadia port project it lost a $1.6 billion power project in the Khulna district in western Bangladesh to India early this year—do not necessarily mean that its future in the South Asian country is wholly bleak. It has advantages over India. India’s influence in Bangladesh may be high at present, but this could change should the AL lose power. Unlike India, China has a good relationship with political parties and politicians across the political spectrum. Additionally, while India enjoys close cultural and social ties with the Bangladeshi people, it also faces fierce opposition there from Islamists and other pro-Pakistan sections as well as those who resent Delhi’s high-handed behavior. China’s relationship with the Bangladeshi public, in contrast, is not tempestuous or prone to swings. Should India’s influence in Bangladesh stir deep resentment in its neighbor, it could face a backlash. China would benefit from that.

The Bangladesh government will need to carefully balance the three power blocs in its region: China, India and the U.S. It needs investment and better infrastructure to trigger economic development but will need to be especially sensitive to India, its giant neighbor which surrounds it on three sides.

Conclusions

Bangladesh’s shelving of the Chinese proposal for a deep-sea port at Sonadia does not bode well for Beijing. It indicates that China wary countries have the capacity and the will to counter its plans and projects. The shelving of the Sonadia port project should serve as a reminder to Beijing that regional and global powers will oppose, perhaps even displace its OBOR-related infrastructure projects with projects of their own, should China’s projects threaten its rivals’ security and other interests.

Dr. Sudha Ramachandran is an independent researcher and journalist based in Bengaluru, India. She has written extensively on South Asian peace and conflict, political and security issues for The Diplomat, Asia Times and Geopolitics.

Notes

1. Author’s Interview, Humayun Kabir, former Ambassador and Secretary in Bangladesh’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Dhaka, April 21.

2. Author’s Interview, Kabir.

3. Author’s Interview, Col. R. Hariharan, a retired Indian Military Intelligence specialist on South Asia, Chennai, April 29.

4. Author’s Interview, Kabir.

5. Author’s Interview, Hariharan.