China’s Tacit Approval of Moscow’s Ukraine Policy

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 44

By:

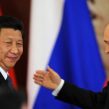

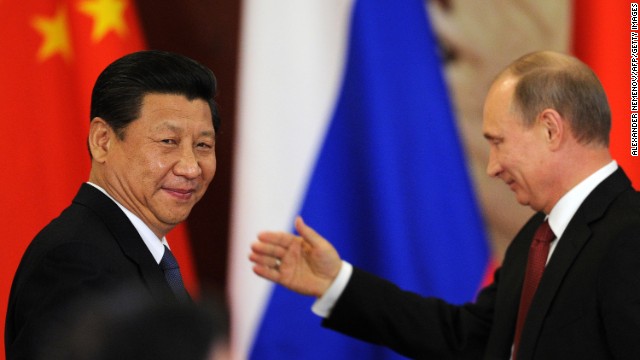

Since Moscow initiated military operations in Ukraine in February 2014, China has seemingly adopted an ambiguous stance as Russia’s annexation of Crimea and destabilization of southeastern Ukraine evoked international condemnation. During the past year, Beijing and Moscow strengthened their strategic partnership by deepening economic ties and enhancing bilateral military cooperation. China’s comparative silence on the Ukraine crisis has given way to unusually blunt remarks from a Chinese diplomat in Brussels who recently expressed tacit support for Moscow (UNIAN, February 27). Such remarks and the continued dynamic growth of Sino-Russian relations contradict efforts by the United States and the European Union to diplomatically and economically isolate Russia. Moreover, they leave open the question as to whether Beijing and Moscow are forming a de facto military alliance.

On February 26, Qu Xing, China’s Ambassador to Belgium urged the West to “stop playing a zero-sum game” with Russia over the Ukraine crisis. In particularly candid remarks, he suggested that Western governments need to “respect” Russia’s interests, appearing to indicate strong Chinese support for Moscow (UNIAN, February 27). China has assumed a publicly ambiguous position on the crisis, although most Russian analysts highlight Beijing’s repeated abstentions in the United Nations Security Council as evidence of some level of support for the Kremlin.

Russian assessments are mixed on issues of the growth of Sino-Russian relations toward some form of alliance or on possible support for Moscow’s actions in Ukraine. Most Russian experts see the former principally driven by economic factors and the latter as more complex—though some level of Chinese backing for Russia is commonly assumed. In terms of economic cooperation, the underlying message coming out of Moscow is “business as usual,” with no indication that Beijing’s policies toward Russia are impacted by events in Ukraine. Russian specialists on China openly declare that economic ties form the long-term basis of the bilateral relationship, and this also feeds into cooperation in multilateral forums such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) or BRICS (loose political grouping of rising economies Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). Bilateral trade is increasing, while the May 2014 energy deal agreeing to supply 38 billion cubic meters (bcm) of Russian natural gas annually to China over 30 years for $400 billion set a new record. Military cooperation is also growing, but has its limits, with Moscow traditionally proving reluctant to supply more high-technology items to Beijing (Rusprav.tv, March 4).

While the future of the Sino-Russian strategic partnership remains open for discussion, a researcher in the General Staff Academy in Moscow has offered some insights into how the top brass may view this relationship, as well as offering additional points concerning China’s diplomatic stance over Ukraine. Colonel (retired) Viktor Gavrilov, a leading researcher in military history at the Research Institute of the General Staff Academy, recently assessed developments in bilateral relations with China regarding whether the strategic partnership is becoming a military alliance (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, March 6).

Gavrilov, no doubt influential in shaping views on the role of Sino-Russian relations within the academy, concluded that the relationship is far from an alliance, nor is the rapprochement forging an “anti-American” bloc. Despite the present problems in Russia’s relations with the US, Gavrilov believes that both Russia and China are still seeking opportunities to cooperate with Washington. In Russia’s case this is reduced to a low level but still extends to the P5+1 Iran nuclear talks, for instance. In this context, Gavrilov believes that Russia and China respect each other’s national interests as they pursue the strategic partnership. His complex assessment of the bilateral relationship notes that other researchers point to a “marriage of convenience” between Russia and China tied to a mutual tacit agreement to support the other party at the international level (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, March 6).

In terms of bilateral military ties, Gavrilov notes a pattern of deepening cooperation both in joint exercises and arms sales. He highlighted Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu’s visit to Beijing in November 2014 to complete the process of registering China as having “special status” as a strategic partner. This means China will receive advanced Russian weapons systems such as the S-400 surface-to-air missile system (SAM) and the multirole Su-35 fighter, as well as the anti-ship missile system “Onyx.” According to Gavrilov, discussions are ongoing to supply the tactical missile system “Iskander-M” and the “Tornado-G” multiple-launch rocket system (MLRS) (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, March 6).

In fact, Gavrilov offers balanced coverage of Beijing’s response to the Ukraine crisis, in the general context of mutual sympathy between Russia and China over territorial issues, while adding that Chinese officials had restated the country’s official adherence to non-interference in the internal affairs of another state and its respect for Ukraine’s “independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity.” In light of China’s internal problems in Tibet and Xinjiang, Gavrilov sees logic in Beijing’s approach to Ukraine. Indeed, this neutral position on the crisis, seemed consistent with China abstaining on key votes in the UN Security Council: Chinese diplomats were careful to avoid any measures that risked conflict escalation. “Although they did not specify what types of actions, in their opinion, may complicate the situation, it seems that these statements were designed for both Russian and Western audiences. In the subsequent voting on the resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations concerning the Crimean referendum, China again abstained, citing the same reasons.” But the author argues that China also opposed imposing sanctions on Russia (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, March 6).

For Gavrilov, China’s actual position on Ukraine, broadly supportive of Russian policy, is rooted in its assessment of the strategic partnership. He notes: “Anyway, Russia’s position reinforces the cautious nature of the Russian-Chinese strategic partnership by demonstrating that in cases of conflicts of interest, Russia will refrain from both strong support and condemnation from its ally in a strategic partnership,” arguing that same calculation explains China’s position on the crisis in Ukraine (Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye, March 6).

In these varied Russian assessments of the development of bilateral ties with China during the past year, a complex and balanced picture emerges tying this relationship primarily to economic cooperation. But the Ukraine crisis has de facto pushed Russia closer to China while the latter has avoided at crucial points any clear condemnation of Russia’s actions. The remarks by China’s ambassador to Belgium add an extra dimension to this narrative. Moscow clearly fails to perceive itself to be “isolated” by the West’s reaction to the crisis, which may be linked to Russia’s close ties with its Asian partner.