Chinese Foreign Policy in South Sudan: the View from the Ground

Publication: China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 13

By:

This article draws on a number of interviews conducted in South Sudan by the author in June 2016.

China’s foreign policy in South Sudan is undergoing significant changes due to a deteriorating security situation and uncertain relations with the South Sudanese government. On July 10, two Chinese peacekeepers were killed outside Juba (People’s Daily Online, July 11). Several other peacekeepers wounded and as a result, much of the embassy staff and several civilian workers were also evacuated (SCMP, July 17). Social tensions and an economic downturn had previously prompted the Chinese embassy to repeatedly issue warnings to Chinese citizens working in the country (Chinese Embassy South Sudan, February 1, March 16, July 9). Diplomatically there are other indications that Chinese forces and companies in the country are not entirely welcome. These events take place against a larger ongoing recalibration of China’s foreign and security policy in Africa (China Brief, June 1; July 6).

Until the outbreak of civil war in 2013, Chinese companies saw South Sudan as a great economic opportunity. Investment in the oil sector grew rapidly, leading to a significant rise in the number of Chinese nationals living there. After 2013, expectations were somewhat moderated but a largely stable situation had given investors hope that the situation could stabilize. However, by the beginning of 2016, even before the most recent outbreak of violence, concerns about China’s presence had already resulted in a downturn in relations. In May, rumors spread in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, that Chinese representatives were calling for the resignation of South Sudan’s Finance Minister, David Deng Athorbei. At the root of crisis was the “Note 2016046” signed by Ma Qiang (马强), China’s Ambassador to South Sudan, and addressed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on May 18, in which he expressed his disappointment in Athorbei’s characterization of Chinese oil production in South Sudan as exploitative (Nyamilepedia, June 7).

China’s interests in South Sudan, and the necessity of navigating its complex politics have required China to be more directly involved politically than it traditionally prefers, skirting Beijing’s long-held principle of non-interference.

China’s Interests in South Sudan

After 30 years of civil war, South Sudan was created in 2011 as part of an international strategy to reshape Eastern Africa. Recent attempts by the international community to establish a transitional government have ended in several outbreaks of violence. In August 2015, the international community brokered the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (ARCISS). This deal brought together the Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU), led by President Salva Kiir of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), and the first Vice President Riek Machar, from the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement in Opposition (SPLM-IO) in April 2016 (South Sudan Tribune, April 28). Elsewhere in the leadership of the TGoNU are ministers from the Former Detainees (FDs) and Other Political Parties (OPPs).

With major economic and political interests in South Sudan, Beijing has strongly advocated for an end to the political crises and violence in the country. With the support of the Juba Chinese Businessmen’s Association and the Chinese Embassy, more than 7,000 Chinese citizens are currently working in the country (including the United Nations Mission in South Sudan – UNMISS) and over 50 Chinese companies are operating in the country. [1]

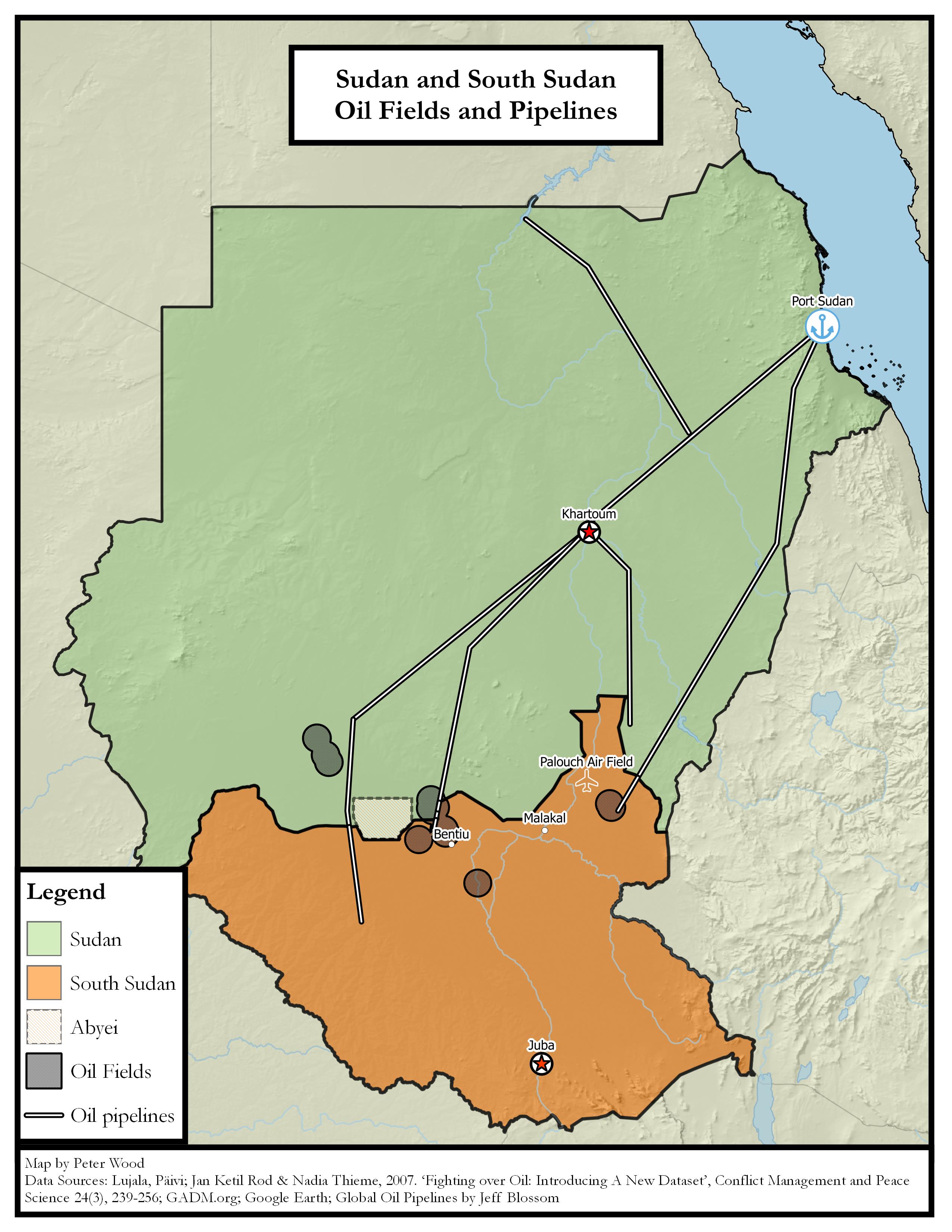

Chinese investment in Sudan’s oil sector predates South Sudan’s independence. After independence, a consortium led by China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) with Malaysia’s Petronas and India’s ONGC Videsh remained, developing oil fields in the newly created state. [2] However, the South Sudanese government has closed most of the oil fields. Along with the threat of violence, this forced Chinese oil companies to seriously cut back their plans for the area after December 2013. Presently, China imports 46 percent of South Sudanese oil via Port Sudan in the Republic of Sudan, but has not restarted exploring options for the construction of new pipelines since 2013. [3] As of June 2016, Palouch is the only remaining field in production oil (see map for more detail).

Since January 2014, oil production has averaged 163,000 barrels per day, with oil revenue equaling roughly $20 million per month. Much of this revenue is siphoned into a large number of poorly supervised South Sudanese bank accounts, creating doubts about the future profitability of CNPC’s investments in the country and making the South Sudanese government grateful to CNPC for not leaving in 2013. [4] However, under economic and social pressure, Juba may have to renegotiate the terms of its agreement with CNPC. [5] The Asia Directorate at the South Sudanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirms that Beijing needs to help South Sudan in the security, mining and agricultural sectors. However, this same source argues that Juba first needs to strengthen the institutions before further opening up South Sudan’s natural resources to Chinese development. [6]

With these priorities in mind, the South Sudanese central government has set up mechanisms to limit China’s development of the country’s resources. With their profits at stake in the aftermath of independence, Beijing turned the federal structure of South Sudan into an advantage: Chinese companies bypassed the central government and took their requests directly to county administrations. Following an increase in Chinese demands being sent to the state governors, the central government decided in 2012 to centralize all such requests at a “China Desk” at the Ministry of Finance. In 2016, continued tensions between the Finance Minister and the Chinese Ambassador led to a transfer of this “China Desk” under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation in 2016. The Asia director of the Ministry is currently setting up a “Ministerial Working Group” gathering a group of technical experts with undersecretaries for each minister involved. The Ministry will select the Ministerial Working Group’s panel of experts, and they will work together on the projects submitted to China inside the framework of the last Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Summit. Several interviewees suggested that Chinese aid is profit-oriented, leading to a misunderstanding between Beijing and Juba and raising the possibility of a conflict over aid in the future. [7]

China and the Mediation Process

Many South Sudanese politicians and thinkers recognize that China’s economic interests in the country have required Beijing to be politically engaged, contradicting its policy of non-interference in local politics. Beijing is currently mediating between South Sudan’s two main political parties in an effort to stabilize the country, which in turn would guarantee the security of its interests. As one member of South Sudanese civil society put it, “Chinese interests would not be secured during the [civil] war so only talking to the government would not work. Thus, engaging with all parties to reach peace was the best way to proceed.” [8]

As one of its first experiences mediating between various political entities in a transitional process, China has engaged with a wider variety of actors than it usually does. In the aftermath of the independence, China began funding several projects for the government and supported the SPLM in building up the newly-born country. The years 2013–2014 represented the high point of Sino-South Sudanese relations, culminating with the sale of Norinco (北方工业) weapons in July 2014 to South Sudan’s armed forces, the Sudanese People Liberation Army (SPLA) (China Brief, October 10, 2014). The deal cemented Beijing as a trust-worthy partner for the South Sudanese government, and as an opponent for the rebels—which subsequently became the SPLM-IO. As a result, on the eve of the outbreak of civil war in December 2013, the Chinese government appeared to be directly supporting the Dinka SPLM against the Nuer rebels. This, in turn, put more pressure on the Chinese government and businesses. As violence escalated in Bentiu and Malakal (see map), 400 Chinese oilfield workers had to be evacuated by the South Sudanese army. [9]

The 2013 civil war triggered a rebalancing of China’s relations with the different parties and further engaged it in the mediation process. China attempted to strengthen relations with the government via the Norinco arms deal. At the same time, however, Beijing invited a delegation of rebels to China to meet Chinese officials and begin building trust. In terms of political structure, Beijing is advocating for a one-party system to maintain unity and avoid having ethnicity-based politics. In this scenario the SPLM would be the overarching structure for the different South Sudanese political groups. Today “the opposition sees China as a key player to speak for economic power. If there is no talk with China, they will stick to supporting the government.” [10]

There are also rumors in Juba that China is still arming both parties. Several sources confirmed than an alleged arms deal with the rebels could be linked to the protection of oilfields controlled by the rebels. This shows that “China engages with the two parties on their own terms” which turns to be quite harmful for the peace agreement. Despite this, China continues to be engaged in the search for conflict resolution: Zhong Jianhua (钟建华), China’s Special Representative for African Affairs, was sent by Beijing to meet with both parties and start the mediation process. [11] China is playing a key role in the mediation process, supporting the UN in the management of Internally Displaced People (IDPs), engaging the South Sudanese army through financial donations (including a recent donation of $1 million) and by sending special representatives. However the South Sudanese government would like China to further engage in the stabilization of the country despite Beijing’s claim that they don’t have the capacity. [12]

At the Crossroads of Perceptions

Chinese efforts to build a positive image across the spectrum of the South Sudanese society through gifts, aid and mediation have not affected the mainstream perception of China in South Sudan. In fact, the domination of government-government exchanges have so far limited any serious change in perceptions among ordinary South Sudanese. This is further reinforced by the tight links between the Chinese UN mission, its Embassy and Chinese businesses.

Some areas have seen improvement in relations. The South Sudanese civil society and government welcomed the arrival of Chinese troops in the UNMISS. The peacekeepers are engaging with local communities and frequently visit Juba University to interact with students. Chinese businesses are also engaging the local community. The Chinese business association came first in late 2013 to donate medicine and food items to IDPs. The largest Chinese company in the country, CNPC, funded the creation of the Protection of Civilians Camp 3 in Juba by paying to clear the land, build fences and set up the first tents. A new computer laboratory in Juba University was also built with funds from CNPC. [13]

Nonetheless, people-to-people exchanges remain limited. Most Chinese workers in South Sudan have limited English language skills. One of those interviewed noted that Chinese intellectuals and officials in China are much more open to discussions than Chinese working in South Sudan. [14] The combination of a language barrier and perhaps a reluctance to discuss issues in South Sudan further limits dialogue outside of government-to-government communication. This has led to widespread South Sudanese dissatisfaction with Chinese businesses.

From Bilateral to Multilateral Engagement

Even though China prefers bilateral engagement, the complex and unstable situation in South Sudan has forced Beijing to engage on a multilateral level with new partners. In fact, Chinese organizations have decided to be part of some joint initiatives in this transition process, and have a seat at the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Committee (JMEC) which monitors the implementation of the 2015 peace agreement. Even though Chinese representatives “passively observe the discussion in multilateral settings,” they are represented in almost all the weekly or monthly meetings organized by the international community in Juba. Their engagement with the recent International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s mission to South Sudan demonstrates that Beijing is also learning how to “better coordinate with other major players to exert pressure altogether.” [15] This pressure would be the main driver of China’s alignment on the IMF’s position. The international community also advocates for China to play a larger role in mediating this crisis at a regional level. Even though Beijing does not appear as a game changer in the peace process, it could use its close relations with Sudan to mediate between the two neighbors. China needs peace to proceed with oil production. [16] The next meeting of the friends of JMEC will take place in Khartoum and will be chaired by China and Sudan.

China’s engagement through the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) displays a shift in its security policy in Africa (ECFR, June 14). In December 2014, Beijing announced the arrival of 700 combat troops in UNMISS. Far away from the oil fields, they were assigned to protect the UN House and the Protection of Civilians camp 1 (PoC1) in Juba. Given the level of violence in the country, being based in Juba appeared to be the safest assignment that the Chinese battalion could receive. UN staff saw this as a litmus test for further engagement in peace-keeping operations, as their lack of experience raised questions among UN officials about their real capabilities to protect PoC1 and the UN House. [17] As the recent attacks on the compound emphasized, however, the situation in Juba is also perilous, and Chinese peacekeepers’ responsibilities and need to prove themselves up to the job has become even more important.

Conclusion

With major investments in oil and a military presence in the UN mission, South Sudan has been a land of challenges and opportunities for China. In this volatile political and economic context, Beijing has taken a number of new political postures such as mediating between parties, deploying a battalion of PLA soldiers as part of a UN mission, engaging on a multilateral level on peace process, and supporting the IMF requests. The eruption of violence in July between the SPLM and the SPLM-IO will most likely reshuffle the relations between the two governments, further putting Chinese foreign policy principles under pressure and highlighting a variety of changes in China’s foreign policy in this transitional period.

Abigaël Vasselier is the Asia and China program coordinator at the European Council on Foreign Relations. She graduated in a Master’s degree in Asian Politics at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and in International Relations at Sciences Po Aix en Provence. She also studied at China Foreign Affairs University in Beijing.

Notes

All interviews were conducted by the author in June 2016 in South Sudan.

1. Interview of an official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. This contrasts with the numbers given by the MOFCOM which counts 140 Chinese companies in South Sudan and 2,000 Chinese on the ground.

2. Given that CNPC is the major shareholder of this consortium, a Chinese official presides this consortium assisted by a South Sudanese Vice-President.

3. Interview of a member of the South Sudan Legislative Assembly. On December 15th, 2013, a civil war erupted between the Nuers and the Dinkas. This conflict opposing the government and the rebel is still ongoing.

4. Interviews of a member of the South Sudan Legislative Assembly and an official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

5. CNPC signed a six-year agreement with the South Sudanese government in December 2014 to increase oil production in three blocks and to rehabilitate aging oil fields.

6. Interview of an official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

7. Interview of an official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation; Member of the South Sudan Legislative Assembly; Interview of an active member of the South Sudanese civil society. China has identified 10 key projects that is willing to fund through a commitment of $60 billion for the African countries. Each Chinese Embassies will serve as a proxy for the government to receive proposals and grant loans. These $60 billion are breakdown into « Ten major plans to improve cooperation with African countries »: $5 billion grants in interests’ free loans, $35 billion for preferential loans, 5 billion additional capital for China-Africa development bank, $5 billion for special loans for entrepreneurs, $10 billion for African production capacity.

8. Interview of a member of South Sudanese civil society organizations.

9. A scholar at Juba University confirmed that the Chinese compounds in the oil fields are still protected by the South Sudanese army; Interviews with a South Sudanese think-tanker and an active member of South Sudanese civil society organizations.

10. Interviews with a South Sudanese think-tanker, a Professor at Juba University, and a member of the South Sudan Legislative Assembly.

11. Interview of a Professor at Juba University.

12. Interview of a member of the South Sudanese civil society.

13. Ibid

14. Interview of a Professor at Juba University; Interview of a member of the South Sudanese civil society.

15. Interview of European diplomat in South Sudan; Interview of a member of the South Sudanese civil society.

16. Interview of a European diplomat in South Sudan.

17. Interviews of UN officials.