Chinese Inroads in DR Congo: A Chinese “Marshall Plan” or Business?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 9 Issue: 1

By:

Since achieving independence five decades ago The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has been ravaged by a dictatorship, war and political strife. Although large in territory and rich in mineral and other precious raw materials, the DRC is a failed state that has been seemingly incapable of maintaining any semblance of stability. With the lowest ranking per capita GDP, life expectancy, literacy rate and a host of other human development indicators, it suffers from rampant corruption on a level of pandemic proportions [1]. Despite an election in 2006 and the deployment of the largest UN peacekeeping mission in history (18,000 troops), war looms in Congo’s Eastern region as clashes between rebel forces and the central government have already displaced up to a million people (All Africa, November 10, 2008). At the same time, large-scale mining contracts and other economic activities have flowed into the DRC in recent years owing to the global boom in demand for raw materials. China—a relatively new comer in this new scramble—has committed to $9 billion for investment in the DRC last year, thus becoming one of the most influential players in the Congolese economy almost overnight.

Changing Domestic Priorities and China-DRC Relations

China’s relations with the DRC after its independence in 1960 have been bumpy at best. While Beijing established revolutionary “brother-in-arms” relations with many other new African states immediately after their colonial occupiers departed, China-DRC diplomatic relations were interrupted twice, and finally stabilized under President Mobutu Sese Seko in 1972. After Laurent Kabila overthrew Mobutu in 1997, bilateral ties continued to improve, and the past decade saw impressive growth in bilateral trade.

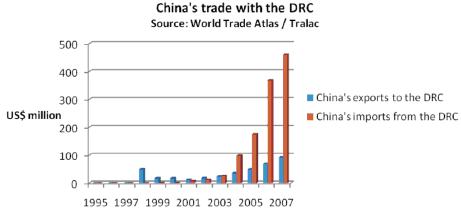

China has strategically shifted away from actively supporting radical ideologies around the world in the 1960s and 1970s and moved toward becoming a major economic investor that proclaims neutrality in political matters. Reinventing itself as the world’s manufacturing power house has resulted in rapid growth of China’s demand for energy, minerals and other resources. As indicated in the Tralac bilateral trade volume figures, Chinese imports from the DRC more than quadrupled from 2004 to 2007 [2]. Despite the DRC’s dismal business environment, China’s huge appetite for copper, cobalt, other minerals and the vast potential of the DRC to provide these metals have driven a range of large, medium and small Chinese companies and banking institutions into the heart of the largest country in Africa. These companies have built some impressive landmark buildings such as the National Parliament, the People’s Palace, and the country’s largest outdoor venue, Stade des Martyrs (The Martyrs’ Stadium). China’s Huawei Technologies Corporation Ltd. has been laying and upgrading the Congolese telecommunications and Internet infrastructure. China has also provided training for students through other aid programs as a part of its overall African engagement strategy [3].

A Chinese "Marshall Plan" or Infrastructure for Resources?

Yet the aforementioned projects are dwarfed by the massive $9 billion dollar, multi-year multi-project deal that the two countries signed in 2008. Negotiations began in the fall of 2007 for the amount of $5 billion, and another $3.5 billion were added to the deal later. Under the terms of the deal, the Export-Import Bank of China pledged a $9 billion loan and finance to build and upgrade the DRC’s road (4,000 km) and rail system (3,200 km) for transportation routes that connect its extractive industries, and to develop and rehabilitate the country’s strategic mining sector in return for copper and cobalt concessions (Reuters, April 22, 2008). In return, China will gain rights to extract 6.8 million tons of copper and 420,000 tons of cobalt (proven deposit)—and the operations are expected to begin in 2013 [4].

The DRC National Assembly approved the agreement in May 2008. After some adjustment on the Chinese side, three major Chinese companies, China Railway Group, Sinohydro Corporation and Metallurgical Group Corporation, controls a total of 68 percent of the new joint venture Sicomines, with the rest of the shares held by Gécamines and the DRC government [5]. By May 2008, 150 Chinese engineers and technical personnel were already in the DRC working on the new joint venture (Northern Miner, May 19, 2008).

The scope of this infrastructure in exchange for resources agreement is unprecedented in many ways. The promised investment is more than three times that of the DRC government’s annual budget ($2.7 billion for 2007). The Chinese Ambassador to the DRC hailed the deal as only the beginning of China’s active promotion of its relations with the DRC. But Congo’s Infrastructure Minister Pierre Lumbi praised it as a “vast Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of our country’s basic infrastructure.” Other than long distance road and rail construction, the package also includes two hydro-electric dams and the rehabilitation of two airports [6]. If fully disbursed, this will be the single largest Chinese investment in Africa. No other countries or international financial institutions have come close to initiating such a massive project in such a short period of time.

Many see the influx of Chinese capital as hope that the DRC can finally move forward with some desperately needed infrastructure development. President Joseph Kabila stated that “for the first time in our history, the Congolese people can see that their nickel and copper is being used to good effect.” Yet critics have lashed out at the arrangement as a sellout of DRC’s natural resources. They argue that the entire arrangement is a ruse intended to veil the Kinshasa’s corrupt regime’s scheme to grab money at the expense of ordinary Congolese. Others have argued that the deal is bad for Congo due to the huge profits for China. Yet others claim that the Chinese investment will further fuel the armed conflicts raging in the most resource wealthy parts of the country.

It is difficult to arrive at a precise estimate on the mineral profits for China’s initial investment. Estimates have ranged from $14 billion to $80 billion (Mining Weekly, September 28, 2008). But with the recession hitting many major developed economies, metal prices have declined sharply in recent months. For instance, copper price has dropped from $9,000 per ton at its peak to the current price of just over $3,000 [7]. Based on various calculations, Chinese profits will have to be adjusted to the market situation.

It is also hard to imagine, with such large fortune at stake, that Beijing would want to see the DRC destabilized. If anything, it is in China’s fundamental interests to build a more secure environment for its long-term presence. That may explain the specific clause in the agreement which specifies that native Congolese workers will compose 80 percent of the work force on all projects.

The Lubumbashi Copper Boom and Bust

It is too early to make definitive conclusions about the $9 billion mega deal as many Chinese copper extractors and smelters in the Southeast province of Katanga have clearly gone through a business cycle of prosperity and decline. When the worldwide demand for copper and cobalt increased, especially from China, many Chinese enterprises, ranging from large to small, went to the mining city of Lubumbashi to set up extraction smelting operations. While the large firms were securely financed and planned to lay the foundations for a long term relationship, many medium and small sized companies, with limited financial flexibility, went to Congo in the hopes of making a quick buck [8]. But after the Congolese government placed a ban on raw ore exports in 2007, these small businesses became mainly involved in processing and trading and found that, even in the midst of the copper rush, earning a quick profit was far from easy.

Unlike well-established Western companies with integrated mining and processing operations, many new Chinese firms were set up for smelting only. They depended heavily on raw materials collected from individual manual miners and once the furnace was up and running many of them found that they did not have enough supplies. The more experienced Western firms, on the other hand, could secure supply for the furnaces from their own large-scale mechanized mining operations.

When the Katanga provincial governments implemented new regulations, demanding that the processor of minerals must supply the raw materials from their own mines, many small Chinese smelting plants were forced to stop their operations due to a lack of resources and increasing cost. While some simply diversified into trading activities for large firms, others were stuck with their investment in land, plant and other equipment [9].

Contrary to popular perception that the all-powerful central government is behind all the advances of Chinese enterprises, almost none of the medium-sized and small Chinese companies receive any kind of governmental assistance. There is not even a Chinese consulate in Lubumbahi [10]. A provincial government minister told the author that there were very few cultural exchange activities between China and the Katanga province, something quite in contradiction to the assumption that China is facilitating its commercial interests through a variety of cultural and socio-political initiatives.

The continuous decline in metal prices has resulted in over 300,000 workers losing their jobs in the mines and factories around Lubumbashi. The renewed fighting and turmoil in the East has also adversely affected the security situation in the resource rich province. In the latest development, more than 10 people, including one Chinese citizen, were killed in Lubumbashi. The government security forces are stretched thin and skyrocketing unemployment is making the city more difficult to manage (Agence France-Presse, December 26, 2008).

Another “Great Game” by the Great Powers?

Despite the deteriorating business operating environment, many Chinese and international businesses continue to expand in the DRC. “There is still money to be made,” as the CEO of a Chinese medium mining firm told the author last fall. However, the situation has grown increasingly bleaker due to the country’s shaky stability and falling commodity prices.

The long-term outlook for China’s role in the DRC is not clear (the same can be said for China’s overall strategy toward Africa). Even if Beijing’s $9 billion infrastructure for resources project is fully implemented, China will still remain a newcomer in the Western dominated mining sector of the DRC. For example, the 6.8 million ton copper deposit concession to the Chinese side is only about two-thirds the amount controlled by a single American firm, Freeport—operator of Congo’s huge Tenke Fungurume mine [11]. Yet there are indications that the United States and other Western countries are concerned about Chinese intentions in the DRC in particular and in Africa in general. There is also an emerging debate on whether the on-going war in North Kivu province is the result of the growing rivalry between the United States and China in the DRC [12]. In a country that has 10 percent of the world’s copper and one-third of its cobalt reserves, 75 percent of Congolese live below the poverty line. It remains to be seen whether Chinese investment actually improves the lives of ordinary Congolese or whether it merely serves to intensify the competition among the great powers for the control of the world’s natural resources and adds to the misery of the local population.

Notes

1. UNICEF, Statistics on Democratic Republic of the Congo, available at https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/drcongo_statistics.html.

2. Gilbert Malemba N’Sakila, “The Chinese Presence in Lubumbashi, DRC,” The China Monitor, Issue 24, October 2008, Centre for Chinese Studies, University of Stellenbosch, p. 7.

3. “Millicom Awards Major Network Contract to Huawei,” News from Huawei’s corporation website, April 13, 2008, available at

https://www.huawei.com/africa/en/catalog.do?id=399.

4. Hannah Edinger and Johanna Jansson, “China’s ‘Angola Model” comes to the DRC,” The China Monitor, Issue 24, October 2008, Centre for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch University; Alfred Cang, “China Railway to Fund $2.9 Billion Congo Mining Project,” Reuters, April 22, 2008, Dow Jones Factiva.

5. “DRC: Loan Tensions,” Economist Intelligence Unit – Country Monitor, August 18, 2008, Dow Jones Factiva.

6. Timothy Armitage, “DRC Outlines US$9.25 Billion Deal with China,” Global Insight Daily Analysis, May 13, 2008, Dow Jones Factiva.

7. The author’s own calculation based on data available at https://ca.advfn.com/.

8. This section is based on the author’s field research and interviews in Lubumbashi and surrounding areas, September 7-12, 2008.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Calculation based on “Mutual Convenience,” The Economist, March 13, 2008.

12. F William Engdahl, “China’s US$9bn Hostage in the Congo War,” Asia Times Online, December 2, 2008.

Acknowledgement: The author would like to thank Stellenbosch University’s Centre for Chinese Studies, Johanna Jansson, and Simin Yu for providing field trip support and research assistance.