Chinese Military Aviation in the East China Sea

Chinese Military Aviation in the East China Sea

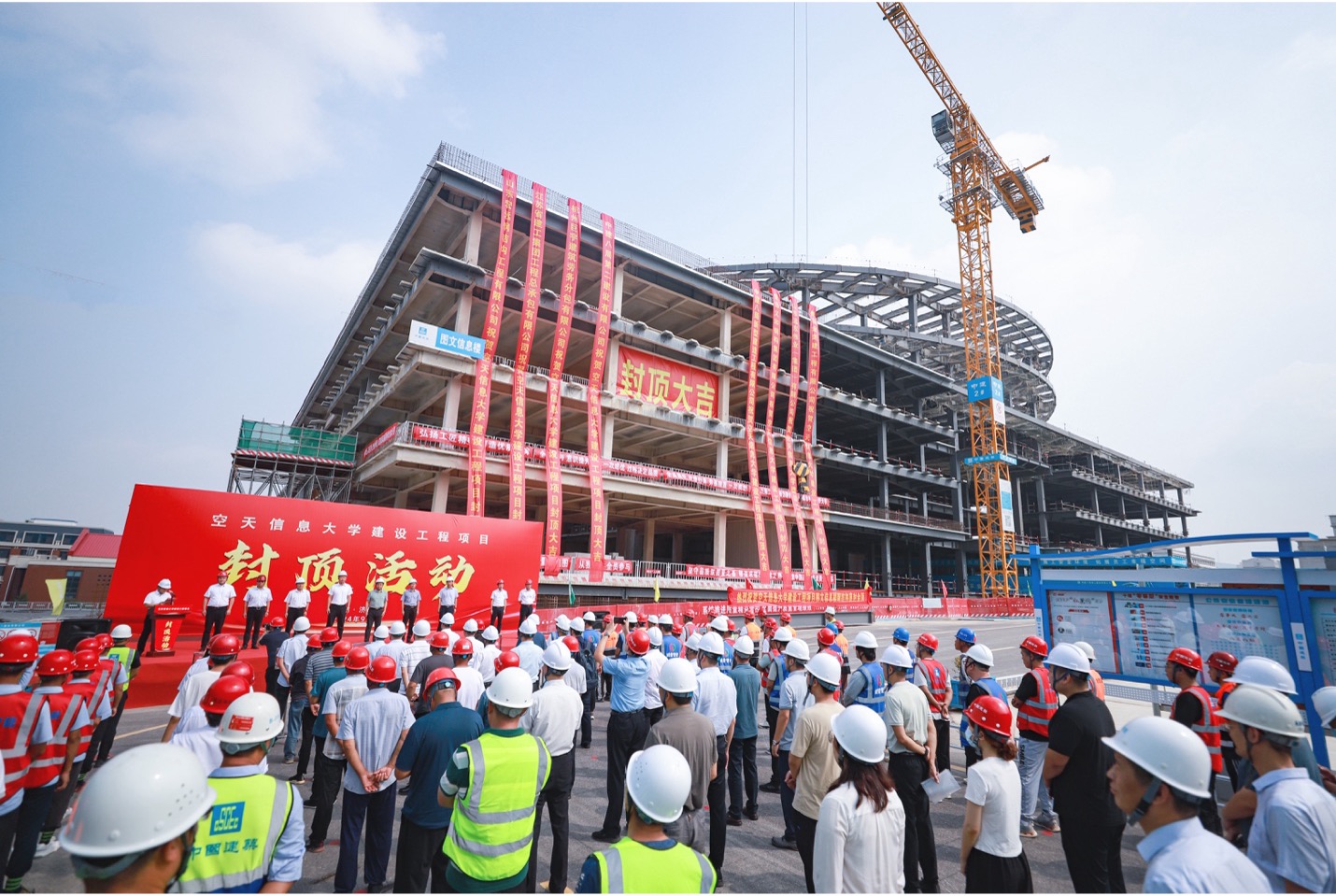

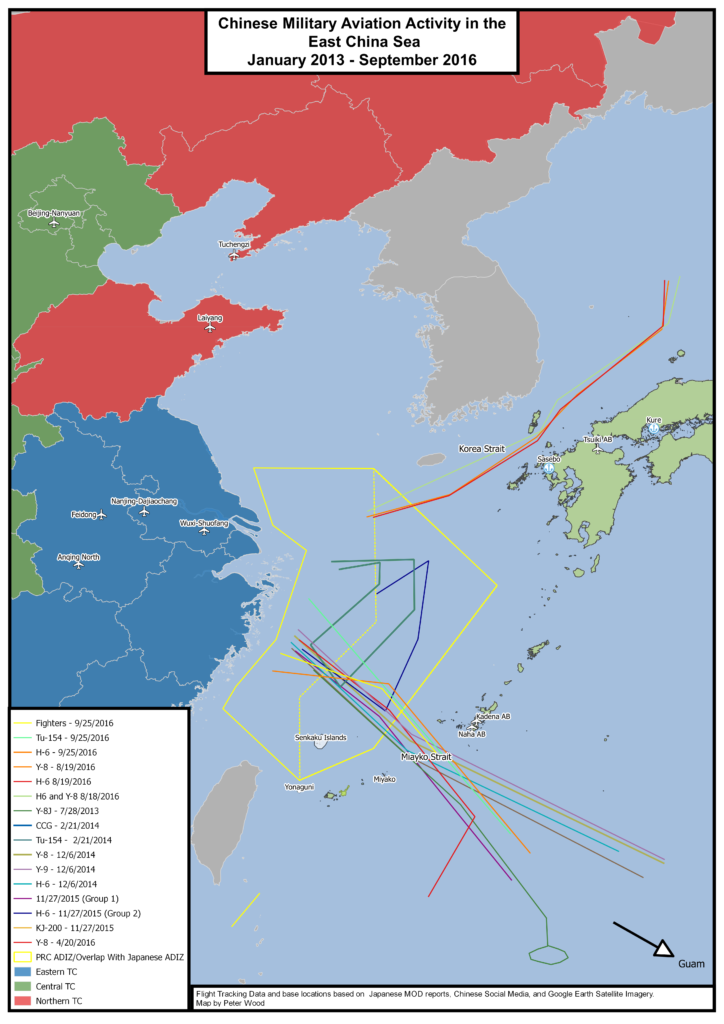

On September 25, the Chinese Air Force performed a series of long-range patrols through the Miyako Strait and into the Western Pacific involving more than forty aircraft (Xinhua, September 25). PLA Air Force spokesperson and Senior Colonel Shen Jinke (申进科) emphasized the routine nature of the patrols and their role in enforcing China’s announced Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) (China Brief, September 3, 2014). These exercises, like those made by other countries, are meant to signal Chinese will to its neighbors, and form an important part of its training. Understanding the context and role of such exercises is important as the Chinese military gains confidence, increases the realism and tempo of its training and, uses such gestures to back up a foreign policy that challenges the status quo in East Asia. Though information about these flights is imprecise, an examination of the aircraft involved, their bases, and what is represented by the schedule and flight paths they take, they can hint at important facets of doctrine and future combat missions and are significant steps toward building a clearer picture of what China wants to do with its Air Force and Naval Aviation.

For the United States and Russia, such flights are routine, as are their interception by fighter aircraft and other surveillance aircraft. But for China, long-distance patrols act as milestones and points of national pride. Other facets, such as an emphasis on nighttime operations (something that is routine for the United States) represent improvements over previous years, when Chinese aircraft only trained during the day. Other frequently mentioned aspects, such as “operating in complex electromagnetic environments” reflect core concepts of Chinese warfighting theory, which envisions a systematic degradation of the ability to communicate via radio, or navigate via GPS-type (Beidou) systems.

Significantly, the origin and frequency of the flights can tell observers a lot about Chinese training and maintenance. China is incrementally improving its ability to effectively monitor and control its air space and self-defined maritime borders. That task imposes significant burdens on China, requiring advanced, overlapping early warning and cueing radars, as well as sufficient fighter and surveillance aircraft. Each airframe is only good for so many flight hours. Intercepting other nations’ aircraft, sending using advanced airborne sensors to search for submarines, or vacuuming up electronic signatures all impose costs that have to be justified in terms of pilot and sensor operator experience gained and military deterrence enhanced.

Drawn from a range of Chinese media sources and reports by the Japanese Ministry of Defense, the following map and database of Chinese military aviation exercises in the East China Sea is an attempt to provide additional context to these exercises.

| Chinese Air Interception Database – 10/20/2016

Full database with citations available here. |

||

| Date | Type | Aircraft Tail Number – Affiliation |

| 2013 | ||

| January 5, 2013 | Y-12 | Coast Guard |

| January 11, 2013 | Y-12 | Coast Guard |

| January 15, 2013 | Y-12 | Coast Guard |

| February 28, 2013 | Y-12 | Coast Guard |

| July 24, 2013 | Y-8J | 9321 PLA Naval Aviation 2nd Division, 4th Air Regiment, Laiyang, Shandong, North Sea Fleet |

| August 26, 2013 | Y-12 | Coast Guard – B-3826 |

| September 8, 2013 | H-6H (2) | 81215 PLA Naval Aviation 6th Naval Aviation Division, Benniu/Danyang, East Sea Fleet |

| October 1, 2013 | Y-12 | Coast Guard |

| October 25, 2013 | Y-8J (2),

H-6G (2) |

H-6G: 81215 PLA Naval Aviation 6th Naval Aviation Division, Benniu/Danyang, Jiangsu, East Sea Fleet |

| October 26, 2013 | Y-8J (2),

H-6G (2) |

81218 PLA Naval Aviation 6th Naval Aviation Division, Benniu/Danyang, Jiangsu, East Sea Fleet |

| October 27, 2013 | Y-8J Early Warning Aircraft (2), H-6G (2) | Y-8J: 9301, 9311: PLA Naval Aviation 2nd Division, 4th Air Regiment, Laiyang, Shandong, North Sea Fleet

H-6G: 81217 PLA Naval Aviation 6th Naval Aviation Division, Benniu/Danyang, Jiangsu, East Sea Fleet |

| November 16, 2013 | Tu-154 | |

| November 17, 2013 | Tu-154 | B-4015 34th Division, 102nd Air Regiment, Beijing-Nanyuan, PLAAF HQ |

| China Announces Establishment of East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone | ||

| November 23, 2013 | Tu-154, Y-8 | B-4015: 34th Division, 102nd Air Regiment, Beijing-Nanyuan, PLAAF HQ

Y-8: 30011 |

| 2014 | ||

| February 21, 2014 | Tu-154, Y-12 | B-4015: 34th Division, 102nd Air Regiment, Beijing-Nanyuan, PLAAF HQ, B-3826 China Coast Guard |

| March 9, 2014 | Y-8 Electronic warfare aircraft, H-6H (2) | Y-8: 9351 PLA Naval Aviation 2nd Division, 4th Air Regiment, Laiyang, Shandong, North Sea Fleet |

| March 14, 2014 | Tu-154 | B-4015: 34th Division, 102nd Air Regiment, Beijing-Nanyuan, PLAAF HQ, Possible ASW role |

| March 23, 2014 | Y-12 | China Coast Guard |

| May 24, 2014 | Su-27 | Intercepted Japanese planes near Senkakus. The article claims the jet was part of 7th Air Division, but the identification number suggests it is part of the 33rd air division based in Chongqing which is equipped with the fighters. *note the Russian-made R-77 AAMs |

| June 12, 2014 | Tu-154 | |

| October 3, 2014 | Y-9 | 9221: PLA Naval Aviation 4th Air Regiment, Laiyang, Shandong, North Sea Fleet |

| December 6, 2014 | Y-9, Y-8J (2), H-6G (2) | 81213 PLA Naval Aviation 6th Naval Aviation Division, Benniu/Danyang, Jiangsu, East Sea Fleet |

| December 7, 2014 | Y-9, Y-8J (2), H-6G (2) | 81214 PLA Naval Aviation 6th Naval Aviation Division, Benniu/Danyang, Jiangsu, East Sea Fleet |

| December 10, 2014 | Y-8J (2), Y-9, H-6 (2) | 81213 PLA Naval Aviation 6th Naval Aviation Division, Benniu/Danyang, Jiangsu, East Sea Fleet |

| December 11, 2014 | Y-8J (2), Y-9, H-6G (2) | H-6G: 81214 PLA Naval Aviation 1st Naval Aviation Division, Benniu/Danyang, Jiangsu, East Sea Fleet |

| 2015 | ||

| February 14, 2015 | Y-9 | Y-9: 9241 PLA Naval Aviation 1st Independent Regiment, Laiyang, Shandong |

| February 15, 2015 | Y-9 | |

| May 21, 2015 | H-6K (2) | H-6Ks: 20110 PLAAF, 10th Bomber Division, Anqing North, Anhui |

| First Flight Through the Miyako strait | ||

| July 29, 2015 | Y-9, Y-8J, H-6 (2) | H-6G: 81218 PLA Naval Aviation 6th Naval Aviation Division, Benniu/Danyang, Jiangsu, East Sea Fleet |

| July 30, 2015 | Y-9, KJ-200, H-6G | H-6: 81218 PLA Naval Aviation 6th Naval Aviation Division, Benniu/Danyang, Jiangsu, East Sea Fleet |

| November 27, 2015 | H-6K (4), H-6K (4), Tu-154, Y-8, KJ-200 | H-6Ks: 20119, 20211, PLAAF, 10th Bomber Division, Anqing North, Anhui

B-4029: 34th Division, 102nd Air Regiment, Beijing-Nanyuan, PLAAF HQ, KJ-200: 33173 26th Special Mission Division 76th Early Warning regiment, Wuxi-Shuofang. Note that the presence of a KJ-200 on this particular mission likely indicates the presence of a unit commander acting as in-air coordinator. Under normal circumstances the commander remains in the base air traffic control tower. |

| December 7, 2015 | Y-8 (2), H-6 (2) | |

| December 10, 2015 | Y-8 (2), Y-9 (1), H-6 (2) | |

| December 11, 2015 | Y-8 (2), Y-9 (1), H-6 (2) | |

| 2016 | ||

| January 31, 2016 | Y-9, Y-8 Early Warning Aircraft | Korea Strait Also entered KADIZ |

| April 20, 2016 | Y-8J | Miyako Strait |

| August 18, 2016 | Y-8 Early Warning (9321), H-6G (81311) | |

| August 19, 2016 | Y-8 Early Warning (9321), 2 H-6G (81212, 81214) | Second day in a row Y-8 #9321 is photographed. Unclear whether the H-6Gs photographed on the second day was also part of the patrol on the 18th. |

| September 25, 2016 | H-6 (4) (20015), Tu-154 (B-4015), Y-8 Intel (unclear, likely model, (2) Fighter Aircraft | |

The scope and frequency of patrols is clearly increasing but overall numbers of strategic bombers and specialized aircraft remain limited. The diversity of aircraft that participate is noteworthy, with airborne early warning, electronic warfare, maritime surveillance as well as bombers and fighters all participating and practicing their respective roles. However, China’s aviation modernization program, while significant, still faces a number of structural hurdles related to personnel and even basic equipment.

One such example is how China deals with maritime aircraft maintenance. Cleaning aircraft that operate at sea incurs additional heavy maintenance costs. Salt water is corrosive and can damage the skin of the aircraft and interfere with sensitive equipment. This requires bases with units that regularly fly over water to have what are essentially large water sprayers like a car wash for aircraft (“wash racks”). U.S. standard operating procedures for naval aircraft (NAVAIR 01-1A-509-2) requires comprehensive cleaning with fresh water and solvents every seven days for aircraft operating at sea. However, a review of satellite imagery of Chinese air bases identified above as well as other PLA Naval Aviation bases revealed no similar facilities. Circumstantial evidence, such as large pools of water in empty spaces on relevant airfields shortly after patrols are known to take place (and no rain is known to have fallen) appear to indicate that the Chinese military relies on traditionally spraying down of its aircraft after long missions by hand.

Despite the sometimes alarmist presentation of the military patrols through the East China Sea by Western media, and the chest-beating tone in Chinese media, such actions really only represent an aspirational capability. China’s military technology has made great strides, but training, and equipment still lag far behind many of its neighbors, not to mention the United States. Tracking investment in new, long-range fighters (such as the Su-35), strategic bombers and specialized aircraft such as early warning and tankers will provide one indication that China is building an air force capable of credible long-range operations. But these platforms can only be brought online with any degree of effectiveness if pilot and maintenance training receive major investment. Specialized support infrastructure, such as the “wash racks” described above, would be an easily detectable indication that China was going to increase its tempo of oversea military flights.

Going forward, continued attention to these patrols in the East and South China Seas, with the context of training, equipment and maintenance capabilities can provide China’s neighbors and the United States a useful metric for measuring its progress as its military continues its modernization program and attempts to enforce its views of maritime and aerospace sovereignty in East Asia.

Note on methodology:

- In most cases, information about these flights, as well as the tracks used in the map are drawn from Japanese MOD reports. Other countries in East Asia, do not report interceptions, due to political sensitivities, or, in the Philippines case, inadequate early warning radar coverage and aircraft. For events presented by the Chinese press, they are less generous with data and do not provide maps of routes taken by aircraft, though in some cases context clues or deliberate background images provides some additional context as to where they have gone. To the degree that it is possible to identify aircraft by serial numbers (bort numbers) I have included them in the table. Some reports do not include the numbers or use unclear photos. Where possible multiple methods of identification have been used, such as verifying that specified bases are home to the listed aircraft with Google Earth imagery. In terms of interpretation, training cycles and even weather should be taken into consideration for Chinese air operations. The Sea of Japan (and nearby areas), for example, sees heavy rainfall and high winds between April and September, particularly June, July and August, periods that roughly correlate with lower incidents of interceptions. Readers are invited to let me know if I have missed anything.

Additional References:

Andreas Rupprecht and Tom Cooper, Modern Chinese Warplanes: Combat Aircraft and Units of the Chinese Air Force and Naval Aviation, Houston: Harpia, 2012.