Chinese Public Opinion and North Korea: Will Anger Lead to Policy Change?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 15 Issue: 1

By:

North Korea’s suspected role in the November 2014 cyber attack on Sony Pictures, a Japanese-owned film studio in Hollywood, has once again dragged China into a discussion of its role in and responsibility for preventing or limiting North Korea’s provocations. Recent revelations of desperate North Korean border guards entering China and killing Chinese civilians over food and money reveal the growing challenges domestically to China’s traditional support for North Korea and suggest one potential opening for U.S. policy makers who seek to change China’s policy—harnessing Chinese public opinion (Xinhua, January 7).

Border Troubles

Despite their espoused alliance, China and North Korea have a long history of issues along their border, including military clashes in 1968 and 1969. Most recently, on January 7, Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) spokesman Hong Lei confirmed that in late December 2014 a North Korean solider had fled his post, crossed the border and killed four Chinese citizens while searching for food before he was shot and killed by Chinese police (Xinhua, January 7). This follows a June 2010 incident, in the midst of China’s support for the North after it sunk and killed 46 South Korean soldiers on the Cheonan naval frigate, which the MFA said involved a North Korean border guard killing three Chinese citizens “suspected of engaging in cross-border trading” (China News, June 8, 2010). Both the 2010 and 2015 MFA public statements were in response to South Korean media reports, highlighting the Chinese government’s reluctance to proactively discuss the negative aspects of its relationship with Pyongyang.

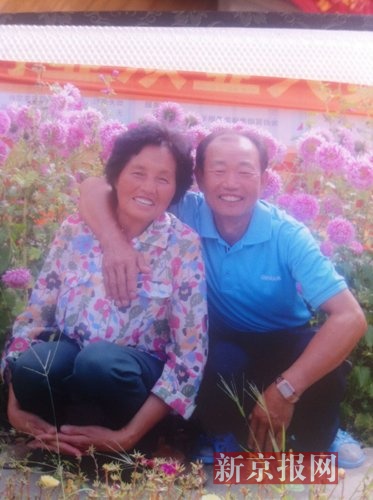

This latest incident touched off a wave of investigative reporting that has so far unearthed at least two largely unknown but similar killings. In December 2013, a “North Korean male” killed a Chinese family and stole 20,000 Renminbi before being arrested by Chinese police (Sohu, January 8). In September 2014, a North Korean civilian killed a family of three and the local Chinese government promptly covered it up (Beijing News, January 6). Sohu reported that killings have been happening since at least 2005—when five North Korean border guards robbed a hotel at gunpoint and killed a Chinese police officer—and that one village right along the border, Nanping, has had over 20 people killed by North Koreans in recent years (Sohu, January 8). Beijing News quoted someone from another village as saying, “they (North Koreans) often come over, wanting money and something to eat… they’re holding a weapon and we don’t dare to not give them something” (Beijing News, January 6).

Reflecting a seemingly growing frustration, Sohu commented, “For two countries who say they have a friendship and ‘blood alliance,’ but time and again have mishaps, and do not have basic crisis control mechanisms and the common corresponding emergency plans, this is not only very strange, but hard to understand” (Sohu, January 8). The Chinese media has also previously covered Chinese public concerns over the environmental damage caused by North Korea’s nuclear tests and also publicized the three hijackings of Chinese fishing vessels by North Koreans, likely the military, in 2012, 2013 and 2014 (Global Times, February 16, 2013; Beijing News, September 24, 2014).

Growing Public Consciousness

While Chinese foreign policy is still largely isolated from Chinese public opinion, the Chinese government is becoming more sensitive to public criticism on hot button issues like territorial disputes with Japan. For North Korea, however, the Chinese government has remained unswayed by growing domestic criticism of Pyongyang and Kim Jong-un. Beijing knows the Chinese public’s distaste for Kim is unlikely to translate into strong criticism of the government that would push it to action, in part because North Korean transgressions against China rarely receive prominent coverage in state-run media and because the government would never allow street protests, compared to its active coordination of some public protests against Japan.

Yet the Chinese government is not deaf to the media and the Chinese public’s changing tone. While the Chinese public is largely unconcerned with the North’s aggression against South Korea, Japan or the United States—indeed, some look fondly on the land of communism—North Korean killings of Chinese citizens will not curry favor for Pyongyang. Chinese netizens often refer to Kim Jong-un as “Fatty Kim the Third” and have been very critical of North Korea, and Beijing’s response, for the hijackings since 2012. Indeed, polling shows that the percentage of Chinese who view North Korea as a military threat rose from 0.4 percent in 2005 to 10 percent in 2014, with many more holding an unfavorable opinion (Mansfield Foundation, April 26, 2005; The Genro NPO, September 9, 2014).

Harnessing Chinese Public Opinion for North Korea Policy

The United States has historically had difficulty changing Chinese government attitudes toward North Korea, but Washington may want to start focusing more on Chinese public opinion by disclosing more information about the direct impact of North Korea’s actions on Chinese civilians when appropriate. The South Korean government appears to have done just this in March 2014, when Seoul revealed that a recent North Korean rocket launch had nearly hit a Chinese passenger plane, leading to a strong Chinese public reaction and subsequent government response (China Daily, March 7, 2014).

While the Chinese government certainly retains some red lines for media censorship about North Korea, its decision to relax restrictions and allow increased criticism may turn into a double-edged sword if North Korean attacks on Chinese civilians continue. The increasingly open public debate about North Korea policy is intended to be a signal to Pyongyang of Beijing’s displeasure, but the Chinese public may in turn begin to pressure the Xi Jinping administration for more action as it learns how costly the relationship really is for China.