Chinese Survey Vessel Incident Puts Malaysia’s South China Sea Approach Under Scrutiny

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 8

By:

Introduction: Challenges to Malaysia’s South China Sea Approach

Malaysia has traditionally pursued what might be termed a “playing it safe” approach with respect to the South China Sea, where it pursues a combination of diplomatic, economic, legal, and security initiatives to secure its interests as a claimant state, while also being careful not to disrupt its bilateral relationship with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This approach stems in part from the balance Malaysia has struck between preserving its claims, which are essential not only to its territorial integrity but also its prosperity, as some fields and platforms used to exploit hydrocarbons lie within China’s declared “nine-dash line.” It also reflects broader realities and constraints, including the relatively distant geographical location of Malaysia’s claims relative to other claimants. It further incorporates the symbolic and substantive importance of maintaining closer ties with China (which is now the country’s largest trading partner), and the limitations of Malaysia’s own military capabilities. [1] It is also consistent with broader considerations in Malaysian foreign policy, including advancing the country’s status as a trading and maritime nation, and preserving global norms and international law as opposed to “might makes right” approaches. [2]

This approach is being tested by increasing incidents in the South China Sea (SCS). Earlier this month, the Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8, accompanied by several coast guard and maritime militia vessels, encroached into Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) to protest Malaysia’s ongoing energy exploration activities. This resulted in simmering tensions between the two countries, which had been ongoing since last year, spilling over into public view. The incident put the new Malaysian government’s approach to China and the South China Sea under greater scrutiny—and revealed constraints that the Southeast Asian state faces in fashioning a response to Beijing’s continued assertiveness amid wider challenges at home and abroad.

Recalibration Amid Growing Concerns

Over the past few years, Malaysian policymakers have recalibrated aspects of the country’s SCS strategy as they become more aware of the challenges posed by China’s assertiveness. For example, under the government of Prime Minister Najib Razak (2009-2018), while there was a commitment to advancing Sino-Malaysian ties, Malaysia undertook a series of activities intended to advance its interests amid rising Chinese activities in the SCS. These Chinese actions included growing incursions by Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) and maritime militia vessels—with the CCG’s presence off Luconia Shoals being a case in point—and interruptions of some of Malaysia’s energy exploration activities (New Straits Times, July 29, 2019). Malaysia’s responses included the historic filing of a joint submissions claim with Vietnam; launching diplomatic protests against Beijing’s actions; increasing patrols around the country’s waters; and deepening defense ties with other major powers, including the United States (United Nations, May 7, 2009; Contemporary Southeast Asia, December 2016).

The pattern of recalibration continued even after the shock election result in May 2018 that ousted Najib and brought the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government to power, led by returning Premier Mahathir Mohamad. During the past two years of the PH government, some of Mahathir’s rhetoric has suggested an inconsistent policy, and Malaysia has agreed to bilateral steps—including what was characterized as a new SCS consultation mechanism in September 2019 (PRC Foreign Ministry, September 12, 2019; Malay Mail, November 4, 2019). However, there were also clear efforts to put a greater focus on the maritime domain and the SCS—as reflected in remarks made by officials, as well as formal documents such as Malaysia’s defense white paper and foreign policy framework (Malaysiakini, June 17, 2019; MINDEF Malaysia, 2020).

Perhaps the most consequential action in this context was Malaysia’s submission of a new extended continental shelf claim to the United Nations last December (United Nations, December 12, 2019). The submission reinforced Malaysia’s determination to consolidate its claims legally amid China’s assertiveness and ahead of the conclusion of a potential ASEAN-China Code of Conduct, as was made clear by then Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah following protests by Beijing (Borneo Post, January 4). On the other hand, tensions between Malaysian, Vietnamese, and Chinese vessels began to play out last year and into 2020. This occurred as Kuala Lumpur began conducting some exploration activities in disputed waters, which in turn spotlighted the question of whether Malaysia would be able to back up its claims and sustain this position over time (AMTI, February 21). With the PH government’s sudden demise in February, the focus shifted to how the new Perikatan Nasional (PN) government led by Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin would seek to contend with the SCS issue within the broader context of Sino-Malaysian relations.

The Survey Incident and Malaysia’s Reaction

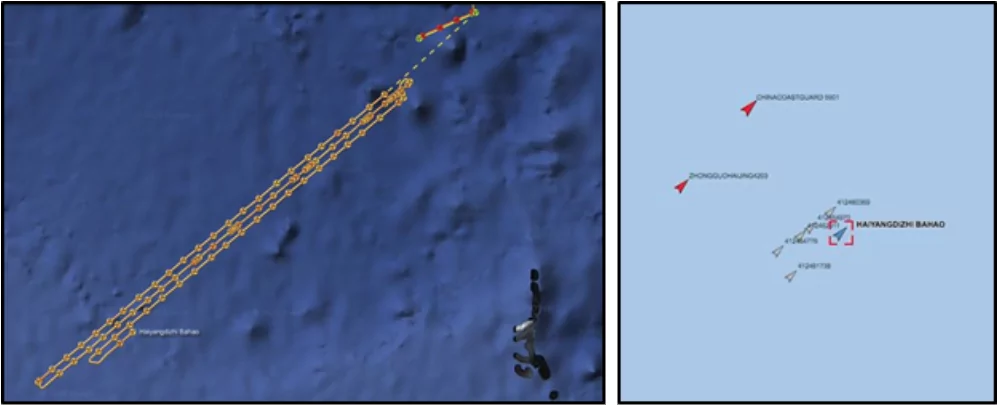

Seen from this perspective, the recent incident represents the first major test for the PN government’s approach to the SCS. On April 16, the Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 (海洋地质八号, Haiyang Dizhi Ba Hao), accompanied by several Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) ships and maritime militia vessels, encroached into the area of Malaysia’s EEZ. On April 17, it moved close to West Capella, a British drilling ship contracted out to the Malaysian state-owned energy giant Petronas. The Haiyang Dizhi 8 reportedly moved in a hash-shaped pattern consistent with carrying out a survey (Harian Metro, April 16; Reuters, April 17). Separately, there were also reports of a transit by two U.S. warships—the USS America and USS Bunker Hill—which sailed near Haiyang Dizhi 8 and the West Capella, as Washington protested China’s SCS conduct (Malaysian Insight, April 23; Reuters, April 21).

PRC Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian said that Haiyang Dizhi 8 “was conducting normal activities in waters administered by China.” Following the incident, Chinese state media continued to focus mostly on highlighting COVID-19 as a source of Sino-Malaysian cooperation (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, April 21; Xinhua, April 24; Xinhua; March 28). But the survey incident, which saw a response by Malaysian vessels patrolling the area, was in line with Beijing’s previous signals to Southeast Asian countries about the risks of carrying out energy exploration within the nine-dash line; and reinforced the PRC’s continued assertiveness in the SCS, even amid the COVID-19 pandemic (Straits Times, April 22; The Diplomat, April 20). This was also followed by a series of subsequent activities by China in the SCS—including the establishment of new administrative districts, and the renaming of features—that generated protests from other Southeast Asian claimants (Berita Harian, April 21).

The incident created yet another bump in what has already been a rocky road for Sino-Malaysian relations. The sudden collapse of the PH party government in February had meant that there would be another round of recalibration of relations between China and Malaysia as the dust settles politically in the new PN government (CGTN, March 9; The Star, March 11). However, before that process took shape the global coronavirus pandemic gripped Malaysia, putting the country in effective lockdown by mid-March. This worsened the country’s economic outlook, and disrupted key aspects of collaboration in Sino-Malaysian relations—including culture, tourism, and people-to-people exchanges (Bank Negara, March 20; The Star, February 4; Xinhua, January 20).

Initially, the Malaysian government’s official reaction to the survey vessel incident was relatively quiet, reflecting the country’s longstanding preference for a low-profile way of handling SCS issues. Although the director of the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA), Zubil Mat Som, confirmed that Chinese vessels had entered the Malaysian EEZ, he refused to specify where the vessels had been and denied that they had operated illegally (Harian Metro, April 16). There was also no formal public statement issued by the government on the matter for several days, until the press statement put out by Foreign Minister Hishammuddin Hussein on April 23. Even then, that statement reiterated key talking points in Malaysia’s SCS approach rather than calling out the PRC for its transgressions—indeed, China was mentioned only once in the entire document (Malaysia FM press statement, April 23).

The government’s initially quiet stance generated some debate within Malaysia, some of which spilled out into the public domain. For instance, Malaysia’s former foreign minister, Anifah Aman, wrote a letter directly to Prime Minister Muhyiddin urging him to act firmly, noting that “a consistent and principled stance is the best way to deal with China’s behavior” (Malaysiakini, April 23). While Muhyiddin himself remained silent, other officials within the government were nonetheless keen to demonstrate that their quiet approach had its merits. Hishammuddin’s statement, for example, ended pointedly: “Just because we have not made a public statement on this does not mean that we have not been working on all the above mentioned, [and] we have open and continuous communication with all relevant parties, including the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America” (Malaysia FM press statement, April 23).

Constraints in Malaysia’s Response

The incident exposed the constraints inherent in Malaysia’s SCS strategy and the PN government’s approach. Whatever may have been going on behind the scenes, Malaysia’s initial public response to the survey incident generated confusion. The lack of a formal official statement from the Malaysian government for several days provided room for speculation and criticism to build among some about its lack of response, and the effects on Malaysian foreign policy (Twitter, April 21). Although Malaysian officials did begin to clarify aspects of ongoing developments later on, by then the government was already on the backfoot and had to counter notions of a Sino-Malaysian “standoff,” rather than actively shaping the narrative up front to its own advantage (Malaysiakini, April 22).

Coordination-wise, the steps taken in response to the incident, and the wider dynamics of Sino-Malaysian relations, appeared to be moving on separate tracks. Strategically, developments that went on in the absence of a government statement—such as the appointment of a new Malaysian special envoy to China—made the policy disconnect more striking and created the illusion of business as usual (Borneo Post, April 24; Astro Awani, April 20). Beyond the few initial details provided by the MMEA chief, there was also little sense of how Malaysia was shaping a whole of government response to the episode, reflecting issues that previous governments had attempted to address as well (New Straits Times, January 15). Pointing to these longstanding issues in his letter to Muhyiddin, Anifah suggested that more active measures previously considered could be taken to address this, including the formation of a special body dedicated to the coordination of maritime affairs (Malaysiakini, April 23).

While Malaysia’s shortfall in maritime capabilities has long been recognized, China’s assertiveness in the SCS has exposed these limitations in recent months and the Southeast Asian state has faced issues in ramping up its defense budget (The Star, December 6, 2019). In October, Malaysia’s then-Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah bluntly told Malaysia’s parliament that recent incidents had created a gulf of credibility between Malaysia’s words and actions in the SCS: “[O]ur assets…need to be upgraded so we are able to better manage out waters should there be a conflict between major powers in the South China Sea” (The Straits Times, October 18, 2019).

Conclusion

The China survey vessel incident is just the latest in a series of developments that have increased the scrutiny on Malaysia’s South China Sea approach. Nonetheless, it is significant: it reinforces the challenges that Malaysia continues to face in recalibrating its outlook on this question, and on Sino-Malaysian relations more generally. It also spotlights the difficulties that the new PN government has encountered in its first major SCS test. How exactly the PN government moves forward on this question remains to be seen. As the two previous Malaysian governments have shown, it is often subtler recalibrations of approaches, rather than disruptive change or total continuity, that will be important to monitor. How Malaysia proceeds will not only be important for the country itself, but also for the region more generally.

Dr. Prashanth Parameswaran is a fellow with the Wilson Center’s Asia Program, where he conducts research and analysis on Southeast Asia political and security developments, Asian security issues, and U.S. foreign policy in the region. The views expressed here are his alone.

Notes

[1] See the author’s previous analysis on this topic in Playing It Safe: Malaysia’s Approach to the South China Sea and Implications for the United States (CSIS, March 5, 2015). https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/playing-it-safe-malaysias-approach-to-the-south-china-sea-and-implications-for-the-united-states.

[2] Johan Saravanamuttu, Malaysia’s Foreign Policy, the First Fifty Years: Alignment, Neutralism, Islamism (Institute of Southeast Asian Studies), 2010.