Coalitions of the Week: BRICS, ASEAN, the G20

Publication: China Brief Volume: 23 Issue: 16

By:

Supreme leader Xi Jinping’s failure to attend the G20 summit in New Delhi this weekend (September 9-10) — thus nullifying the possibility of a meeting with top Western leaders including American counterpart President Joe Biden — is symptomatic of the isolation that China is facing on the international stage. Instead, Xi is sending Premier Li Qiang, not only to New Delhi but also to a series of meetings between Western and Asian powerhouses, including between the United States, Japan, and the ten members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Jakarta, Indonesia. ASEAN members seem eager to seize the opportunity to promote free trade and high-tech cooperation with the United States and its Western allies, agreeing this week to inject more funds into projects under the U.S.—ASEAN Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (InvestASEAN.org, September 7; The White House, September 5). By contrast, China’s recent business ties with ASEAN nations has been dominated by a continuous exodus of multinational corporations moving production bases from China and into countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia.

Xi’s absence has raised eyebrows, particularly due to the fact that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary has pulled out all the stops when it comes to expanding the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) clout on the global stage, even while ignoring worsening socio-economic conditions at home, such as rising youth unemployment, declining exports and consumer spending, and disappointing new home sales. Deemed a crypto-Maoist by China’s critics, the CCP chief remains convinced that, in the words of both Mao and himself, “the East is rising and the West is declining,” conditions which would allow the PRC to seize the geopolitical high ground given “opportunities that only come once in a century” (Gov.cn, June 23 ; Xinhua, March 23).

Another few BRICS in the wall

One of the Xi leadership’s major acts has been to build up a so-called “axis of non-democratic states” to countervail a United States—led “anti-China” coalition, which includes the EU, NATO, AUKUS (the defense pact between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States), the QUAD (a “security dialogue” between the United States, India, Japan, and Australia), as well as long-time American allies in Asia, most notably Japan and South Korea (China Brief, July 5). At a trilateral summit between the leaders of the United States, Japan, and South Korea held in August at Camp David near Washington, D.C., President Biden, President Yoon Suk Yeol, and Prime Minister Fumio Kishida agreed to strengthen military cooperation, including the joint development of next-stage submarines and missiles. The trio also vowed to defend the status quo in the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea (The White House, August 18; Aljazeera, August 27).

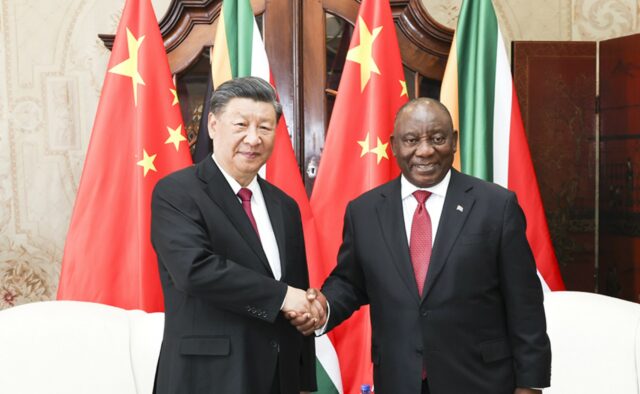

The recently held summit of the BRICS group of countries in Johannesburg –— which Xi did attend — has apparently boosted Xi’s goal of forming a non-Western alliance to counter the “eastward move” of NATO and other alleged hostile measures aimed at reining in China. However, only six new members — Saudi Arabia, Iran, United Arab Emirate, Egypt, Argentina and Eritrea –— formally joined the bloc, and not the originally planned 20-odd nations (VOAnews, August 24). At the closing ceremony of the Johannesburg get-together, Xi, leader of the most powerful BRICS member, asked rhetorically, “should we work together to maintain peace and stability, or just sleepwalk into the abyss of a new Cold War?” (CGTN, August 23). The supreme leader posited China as the leader of a “new world order” (Council on Foreign Relations, August 31) consisting of nations committed to “win-win” principles. He also made a pitch for the wider use of the Chinese renminbi as a potential substitute of the United States dollar.

However, a couple of major BRICS economies, notably India and the newly-admitted Saudi Arabia, have maintained close defense relationships with the United States, and are dependent on Washington’s supply of advanced weapons and military technology. While Saudi Arabia seems willing to consider billing a portion of their petroleum sales to China in renminbi (Geopoliticaleconomy, August 10; Al-monitor.com, April 28), the dollar remains very much the currency of choice in oil and gas transactions in the Middle East and worldwide.

India has run afoul of the Xi leadership by — among other things — flagging its close ties with the Biden administration. In an interview with Indian media immediately after the BRICS summit, Prime Minister Narendra Modi slammed an unnamed country for setting “debt traps” by extending loans to developing countries to finance infrastructure projects that they cannot afford. At the same time, Indian Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal took another step away from China, stating that New Delhi has given up joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Pact (RCEP), the free trade area dominated by the PRC, because doing so would lead to India suffering from trade imbalances (Economic Times, August 28; India Today, August 26).

America’s moves

China’s relations with several of its important neighbors also soured after the publication last week (Guangming Online, August 28) of a new standard PRC map which calls disputed border areas with India, Russia, Japan, and Taiwan “Chinese territory.” Moreover, it has deemed almost the entire South China Sea as Chinese territory, thus angering Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia — ASEAN countries that are also claimants to the disputed territories. This seems to be the Xi leadership’s reaction to both enhanced military cooperation between India, Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines, as well as preliminary defense agreements inked between NATO and ASEAN states including the Philippines and Vietnam (French Radio International, September 2; China Daily, August 28).

Regarding United States-China ties, Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo’s trip to Beijing produced no concessions on either side in the areas of tariff reduction or Washington’s decision to restrict American investment in “sensitive sectors” in the PRC. Overall, cumulative American investments in China as well as United States -China trade, have continued to drop in the first half of 2023, thus dealing a big blow to Beijing’s hopes for a post-pandemic recovery. Raimondo even quoted individual American firms as saying that China was “uninvestable” (Reuters, August 29; SCMP, September 7; AsiaFinancial.com, September 4). Coinciding with Raimondo’s supposedly fence-mending visit, Washington announced military sales to Taiwan for the first time under the Foreign Military Financing Mechanism. Given that this program is usually reserved for aid to sovereign states, the arms sale amounted to at least a theoretical recognition by Washington that Taiwan is tantamount to an independent country (VOAnews, September 6).

Xi’s blues

Xi, who has only made two foreign visits since the end of the Covid-19 pandemic in late 2022, has largely stayed away from giving direct instructions on how to revive the Chinese economy, or on how to repair China’s economic relationship with the United States-led Western alliance. In a virtual speech to the Global Trade in Services Summit of the 2023 China International Fair for Trade in Services (CIFTIS) held in Beijing earlier this month, Xi reaffirmed Beijing’s commitment to pushing forward a high level of opening up, saying that “China will open wider in sectors including telecommunications, tourism, law and vocational examinations, and widen the market access in the services sector” (China Daily, September 2). He added that “in developing the services sector and trade in services, China will work with all countries and parties to advance inclusive development through openness, promote connectivity and integration through cooperation, foster drivers for development through innovation, and create a better future through shared services” (Xinhua, September 2).

However, the Xi leadership has failed to announce new favorable policies to attract multinationals, which might include selectively lowering taxes for the China-made products of Western companies or rendering it easier for international companies to remit foreign exchange out of the country. Moreover, the decision by the State Statistical Bureau not to release figures on youth unemployment or the sale of new land seems symptomatic of Beijing’s penchant for favoring a diktat economy over market-oriented transparency. And finally, the expected slow-down in economic growth and the heavy-indebtedness of different levels of governments and state-owned enterprises, the CCP administration lacks the funds to finance intercontinental infrastructure projects associated with the Belt and Road Initiative, which have highly lifted the country’s international profile (Council on Foreign Relations, April 6; Green Finance and Development Center, February 3).

Conclusion

Given this series of diplomatic and economic setbacks, Xi’s absence from the G20 summit this weekend is all the more extraordinary. Beijing is forfeiting the initiative at a critical international meeting at a critical time. One might speculate as to Xi’s reasoning: Perhaps fears of more setbacks due to the CCP’s support for Russia’s war in Ukraine or domestic political tremors at home — including a rumored upbraiding by party elders during Xi’s Beidaihe retreat earlier in August — are more substantial than they look from a distance. For now at least, it seems clear that even if Xi is delegating responsibilities, he is not sharing his power; though that is looking increasingly like a sign of weakness.