CONVICTION OF RUSSIAN BLOGGER: HARBINGER OF A WIDER ON-LINE CRACKDOWN?

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 5 Issue: 133

By:

Last week, a blogger in the Komi Republic was convicted of “inciting hatred or enmity.” Some observers fear that the case sets a dangerous precedent for curtailing freedom of speech on the Internet. Other observers have gone farther, predicting that the authorities are planning to impose more systematic Internet controls and limitations.

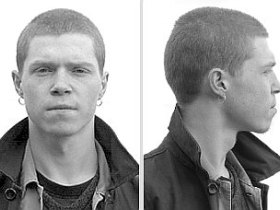

In February 2007 Savva Terentiev, a 28-year-old musician from the city of Syktyvkar, located in the Komi Republic more than 900 miles north of Moscow, wrote on a friend’s blog on the LiveJournal portal that the police were “dumb, uneducated representatives of the animal world” and should be burned periodically in town squares “like at Auschwitz” (New York Times, July 8). The following month, police raided the apartment where Terentiev was living and later charged him with violating Part One of Article 282 of Russia’s Criminal Code, which concerns “actions aimed at the incitement of national, racial, or religious enmity, abasement of human dignity, and also propaganda of the exceptionality, superiority, or inferiority of individuals by reason of their attitude to religion, national, or racial affiliation.” On July 7, after a 10-month trial, Terentiev was found guilty and received a one-year suspended jail sentence (Reuters, July 7; Rossiiskaya gazeta, July 9).

After Terentiev’s prosecution was launched, he wrote an open letter to President Dmitry Medvedev stating, “It is our duty to take responsibility for words on the Internet, but…I did not call for the inflaming of social hatred toward the employees of the police department” (Reuters, July 7). Noting that Savva Terentiev was accused of “inciting hatred and enmity toward a social group,” Aleksandr Privalov, research editor for Ekspert magazine, questioned the use of Article 282 in prosecuting him.

“The police are not a social group that needs to be protected from a scoundrel propagandizing hatred and enmity toward it,” wrote Privalov. “The police are people who are hired by society for its–society’s–protection. If these people do their job badly (and they often do it not simply badly, but criminally badly–even officially, four thousand criminal cases are brought against policemen annually), then the society that is badly protected by them has the complete right to call them names. If obscenity is used, fine [the user] according to Russian Federation Code of Administrative Offenses. If threats are made,…punish [those who made them]. But simply for the fact that someone strongly dislikes you? And tomorrow bandits and raiders will demand jail sentences for inciting hatred toward their social groups” (Ekspert, July 14).

Some Russian press freedom advocates have said that criminal cases against bloggers like Savva Terentiev will not be sufficient to limit free speech on the Internet and have suggested that the authorities will act more systematically to do so. “There are only two possibilities for limiting free speech on the Internet: the former Cuban and the current Chinese variants,” Igor Yakovenko, secretary of the Union of Russian Journalists, told Novye izvestia. “The Cuban [variant] was where the citizens did not have the right to have a computer without special permission. The Chinese [variant] is where owners of computers are forbidden from using certain words.”

Likewise, Alexei Simonov, chairman of Glasnost Protection Foundation, said such criminal cases are simply sporadic “demonstrations of intentions” by the powers-that-be. “I don’t think that the authorities will be able to limit freedom on the Internet this way,” he said. “But since the authorities will still need to exert influence on the Internet, they will choose more massive and repressive means of influence, as they did, for example, with NTV and TV-6” (Novye izvestia, July 14). NTV, which was the flagship of Vladimir Gusinsky’s Media-Most empire, was taken over by Gazprom, the state-controlled natural gas monopoly, in 2001, while TV-6, another privately-controlled television channel, was shut down by the Russian authorities in 2002.

On July 11, just a few days after Savva Terentiev’s conviction, Interior Minister Rashid Nurgaliev said that the Interior Ministry, Federal Security Service (FSB) and Justice Ministry should work with the parliament on legislation designating the Internet as “a means of mass information, with all the legal consequences that flow from that for holders of subversive websites” (www.newsru.com, July 11). Last February Vladimir Slutsker, a member of the Federation Council, the upper house of Russia’s parliament, introduced legislation that would force domestic websites with more than 1,000 daily visitors to register as media outlets and thereby make them subject to the same regulations as other media, including the restrictive law on extremism (see EDM, April 7).

President Dmitry Medvedev claims to support free speech on the Internet. “It’s possible to go on to the Internet and get basically anything you want,” he said in an interview with Reuters last month. “In that regard, there are no problems of closed access to information in Russia today; there weren’t any yesterday; and there won’t be any tomorrow” (Reuters, July 7). In an earlier comment, however, Medvedev was somewhat more equivocal, stressing the need to “respect the law.” The answer to “the delicate question of the relationship between freedom of speech and responsibility” in cyberspace, he said during a forum devoted to the Internet in April, “is fairly simple: laws must be respected everywhere … at the same time, the state should take a calm, fair position” toward Internet users (see EDM, April 7). As the Savva Terentiev case demonstrates, views of what constitutes “a calm, fair position” can differ, and Russian law frequently proves to be a flexible tool for limiting rights rather than protecting them.