CPEC: “Iron Brothers,” Unequal Partners

Publication: China Brief Volume: 18 Issue: 1

By:

Serious differences have come to the fore between China and Pakistan over the $60-billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). At a Joint Working Group (JWG) meeting at Islamabad in November 2017, China announced its decision to suspend funding for at least three road projects in Pakistan, pending the release of “new guidelines” (Dawn, December 5, 2017). Only a few days earlier, Pakistan rejected Chinese funding for the $14-billion Diamer-Bhasha dam project and withdrew its request for inclusion of this project in CPEC. Pakistan objected to Chinese conditions, which included Chinese ownership of the project, operation and maintenance costs and securitization of the project by pledging another operational dam. According to Pakistan’s Water and Power Development Authority Chairman Muzammil Hussain, these requirements “were not doable” and against Pakistan’s interests (Express Tribune, November 15, 2017). China has denied these allegations (Global Times, December 12, 2017).

China and Pakistan often hold up CPEC, a flagship venture of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as a symbol of their co-operative partnership. Recent developments indicate serious differences between the two countries. Differences are inevitable between partners, even those that claim to be ‘iron brothers.’ However, the Sino-Pakistani relationship in CPEC is an unequal one. Not only will CPEC benefit China more than Pakistan, Beijing also calls the shots. It is even cracking the whip to ensure Islamabad concedes its demands on contentious issues. Islamabad’s vulnerability to Chinese pressure can be expected to increase especially after the US’ decision to suspend security aid amounting to around $1.3 billion annually to Pakistan in early January.

Corridor and More

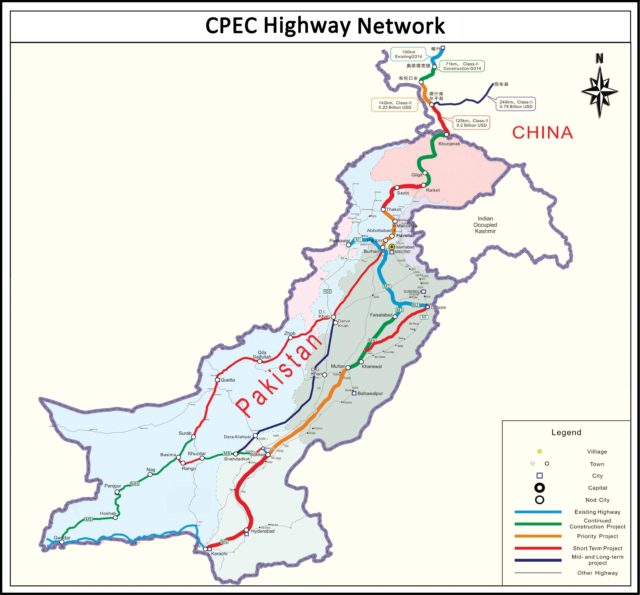

Although CPEC is widely seen primarily as a “connectivity corridor”, power plants and special economic zones (SEZs) are also being developed. The project is envisioned as linking China’s economically underdeveloped Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region with the deep-sea port of Gwadar in Pakistan’s Baluchistan province through a network of highways, railways, oil and gas pipelines and fiber optic cables (China Brief, July 31, 2015).

However, little was known about its massive plans for Pakistani agriculture. Original documents of CPEC’s long-term plan, whose details were disclosed by the Pakistani English daily Dawn in May, reveal that Chinese enterprises will lease thousands of acres of Pakistani agricultural land to set up ‘demonstration projects’ to introduce new seed varieties, pesticides and irrigation technologies. Facilities for processing, storing and transporting, grains, fruits and vegetables are also being set up, indicating that access to the full supply chain of Pakistan’s agriculture is an important goal of CPEC (Dawn, June 21, 2017). China appears to be using CPEC to strengthen its food security, a key priority of President Xi Jinping (China Brief, March 2, 2017).

CPEC’s scope is breathtaking. In addition to opening up Pakistan’s domestic economy to Chinese participation on an unprecedented level, it will result in China’s deep penetration of Pakistan’s security, society and culture. The cross-border fiber optic cable project, for instance, will establish fast and reliable connectivity routed through China. It will facilitate terrestrial distribution of broadcast TV that is envisioned as carrying Chinese culture into Pakistani homes (Dawn, October 3, 2017). In addition, China is promoting the study of Mandarin and has set up dozens of language schools across Pakistan. In fact, under a Memorandum of Understanding between the governments of Sichuan and Sindh provinces, Mandarin was made a compulsory subject for school children in Sindh. The number of Chinese nationals working and living in Pakistan has also surged in recent years, transforming entire neighborhoods in Pakistani towns into ‘Chinatowns’ (Herald, January 28, 2017; Dawn, June 4, 2017). Pakistan faces a sinicization of its economy, population and culture.

Pakistani Expectations and Apprehensions

Often described as a ‘game changer’, CPEC is expected to boost Pakistan’s Gross Domestic Product growth rate from 5 to 7.5 percent and create 2 million direct and indirect jobs between 2015–2030 (The Nation, October 8, 2016). Pakistan’s government speaks glowingly of its potential to transform Pakistan into a regional economic powerhouse, and even make it the next “Asian Tiger” economy (CPEC, Government of Pakistan). In the months following CPEC’s inauguration in April 2015, opinion pieces were effusive in their praise of China. Beijing was hailed for going out of its way to “substantially strengthen” bonds with Pakistan. Its economic aid was looked upon as largesse and indicative of “the commitment of the Chinese leadership towards Pakistan” and its 207 million people (The News, April 27, 2015; Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2017).

Pakistan’s former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif has said that Baluchistan will be CPEC’s “biggest beneficiary” (The Nation, May 5, 2017). Baluchis, however, are not convinced. CPEC evoked little optimism among them from the start, and they fear that CPEC would benefit outsiders rather than locals. An additional concern is that migration of workers to Gwadar will change the demographic profile of the province, leaving the group a minority (The News, June 4, 2016). Baluch opposition to the project is strong and has even been expressed violently. Baluch militants have carried out several attacks on workers from outside the province, includes those from China (Gandhara, September 29, 2016; Herald, July 14, 2017).

Over the past year, a small but vocal group of analysts have begun expressing unease over what CPEC will bring Pakistan. In particular, they are calling for transparency on deals (Dawn, July 30, 2017; Daily Times, November 5, 2017). In Dec 2017, the Pakistani government released a summary of CPEC’s Long-Term Plan (The News, December 20, 2017). But even this sheds no light on the terms and conditions of agreements, project timelines or the exact nature of Chinese funding.

Documents disclosed by Dawn and information trickling out of official meetings point to troubles ahead. The most important is the looming debt trap. Economists have highlighted the estimated $90 billion in debt that Pakistan will have to repay China over 30 years (Express Tribune, March 12, 2017). The consequences if Pakistan is unable to repay are unclear, though it is possible it would meet the fate of Tajikistan and Sri Lanka, which ended up ceding territory to China in lieu of unpaid debts (Dawn, March 23, 2017).

CPEC’s terms and benefits disproportionately favor China. The state-run China Overseas Port Holding Company, for example, which will operate Gwadar port for a period of 40 years, is set to take 91 percent of gross revenue collection from terminal and marine operations and 85 percent of gross operations revenue from the Gwadar free zone (The Nation, April 20, 2017). SEZs are being are being set up exclusively for Chinese companies where they will be exempted from taxes (Dawn, March 9, 2017). The CPEC plan provides the Chinese with visa-free access to Pakistan. There is no such reciprocal arrangement for Pakistanis and China’s visa rules for Pakistanis have in fact tightened (Dawn, September 2, 2017). There is even little clarity regarding who will run or supervise the elaborate electronic surveillance system that China will install in Pakistani cities (Hindustan Times, June 13). With such free rein over debt, policing and tax collection, there is concern over CPEC’s implications for Pakistan’s sovereignty. It could turn Pakistan into a Chinese colony (Economic Times, June 12, 2017). Parallels are being drawn between CPEC and the East India Company, the forerunner of British colonial rule in the Indian sub-continent (Dawn, October 18, 2016).

China’s Concerns

Although the Chinese government has avoided publicizing its concerns over political instability in Pakistan, there is apprehension in China over the implications of unrest and insecurity for CPEC (Global Times, September 9, 2016 and China Daily, December 12, 2016). Indeed, protests at project sites about issues like compensation for land, environmental concerns and exclusion of locals from project benefits delayed projects (Dawn, July 7, 2017).

Another concern is violence targeting CPEC projects and Chinese nationals in Pakistan. The corridor links Xinjiang with Baluchistan, both turbulent regions, and runs through the insurgency-wracked Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and disputed Gilgit-Baltistan territories. Bomb blasts and grenade attacks have killed scores of Pakistani workers and Chinese nationals employed in CPEC projects (Global Times, May 25, 2017). China is worried that Uighur militants will attack Chinese targets in Pakistan. In December 2017, the Chinese Embassy in Islamabad warned its nationals of a “series of terror attacks” targeting “Chinese-invested organizations and Chinese citizens” in Pakistan (Dawn, December 8, 2017). In October 2017, it raised concern over a possible terrorist threat to its ambassador in Islamabad from the East Turkestan Independence Movement (ETIM) (Dawn, October 22, 2017).

The unsettled status of Gilgit-Baltistan, territory that is part of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) over which India lays claim, worries China as it raises questions about the legality of CPEC projects here (Express Tribune, January 7, 2016). Pakistan’s upcoming parliamentary elections are an additional cause for concern. While Pakistan’s main political parties are not opposed to CPEC, there are differences in their priorities. The ruling Pakistan Muslim League—Nawaz (PML-N) prioritizes projects along CPEC’s relatively calm eastern route, which runs through its stronghold, Punjab. However, should the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) form or be part of the next government it can be expected to shift focus to the turbulent western route. A change in government could lead to a review and or change in the deals (Global Times, Aug 3, 2017).

Pressure on Pakistan

To reassure China on the safety of it nationals and investments, Pakistan has set up a 15,000-strong Special Security Division and raised a naval contingent to protect Gwadar port (China Daily, March 15, 2017). At China’s urging it has also cracked down on ETIM, and Baluch and other militants opposed to CPEC (Pakistan Today, October 18, 2015).

Under Chinese pressure Pakistan has taken decisions that are not in its interest. Chinese prodding has forced it to begin taking steps to formally integrate Gilgit-Baltistan (Express Tribune, January 7, 2016). While this may provide legal cover for Chinese projects in Gilgit-Baltistan it will cost Pakistan the goodwill of Kashmiri separatists (The Wire, March 20, 2017).

China’s decision to suspend funding for the three road projects is another example of such pressure and is possibly aimed at disciplining Pakistan for its defiance of Beijing over the Diamer-Bhasha project (FirstPost, December 7, 2017). China is reportedly keen to have the Pakistani Army put in charge of CPEC projects as its involvement is expected to improve efficiency and speed up execution of projects, guaranteeing CPEC’s success (European Foundation for South Asian Studies, December 8, 2017). Formalizing the army’s role in CPEC could become part of the new guidelines.

Pakistan’s defiance of China on the Diamer-Bhasha project is likely to be short-lived. Its economy and military are far too dependent on China for Islamabad to resist Beijing’s pressure for long. This dependence has deepened following the United States’ decision to cut aid to Pakistan. In a sign of things to come, the Pakistani government reacted to the US announcement by allowing the renminbi to be used for bilateral trade and investment activities, reversing an earlier decision in November barring the use of renminbi on the grounds that it would undermine Pakistan’s economic sovereignty (Business Recorder, January 8; Express Tribune, November 21, 2017). China’s grip over Pakistan in CPEC has tightened.

Conclusions

China and Pakistan are likely to continue to differ on issues related to CPEC. However, these are unlikely to derail the initiative, given their strong relationship, Pakistan’s deepening dependence on China and Beijing’s determination to make a success of BRI’s flagship venture. Other countries participating in BRI can draw lessons from Pakistan’s experience with CPEC. They can expect massive Chinese investment but not on generous terms. Chinese funding is not largesse and will extract a heavy price. As in Pakistan, they can expect sinicization of their economy, population and culture. Countries weighing the costs of Chinese investment should factor in Chinese interference in their political system.