China-Russia Relations Reality Check

Publication: China Brief Volume: 18 Issue: 1

By:

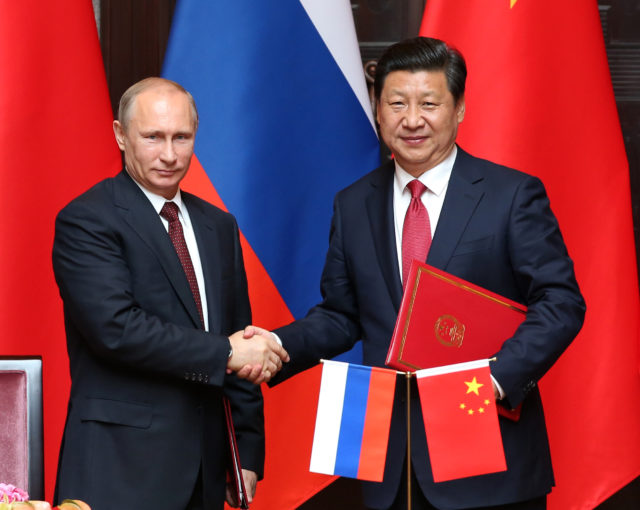

In 2017, China and Russia trumpeted the closeness of their relationship, calling it a historic highpoint. Xi Jinping has made good relations with Russian President Vladimir Putin a priority, visiting Russia six times and meeting with Putin on 21 occasions since taking office.

Authoritative statements by Chinese government mouthpieces, officials and think tank researchers suggest that China views Russia as a key partner in advocating its view of the international system.

Su Xiaohui, a scholar at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs-affiliated China Institute of International Studies has argued that Sino-Russian relations were a “model” or “show-room” of “New Type International Relations” (People’s Daily Overseas Edition, October 31, 2017).

Though Chinese characterizations of the relationship present a united front, they also highlight China as the leader in the partnership. In October of last year, Chinese Ambassador to Russia, Li Hui (李辉), wrote an article in the Russian newspaper Izvestia describing the implications of the 19th Party Congress and Xi Jinping’s leadership for the Sino-Russian relationship (Guangming Daily, October 29, 2017; People’s Daily Online, October 27, 2017). Behind the platitudes and glossing over of a complicated history was a clear message: Russia is open to following China’s lead. Indeed, while Putin articulates his own policies—sometimes in contradiction of China’s—when it comes to key votes in the United Nations, Russia follows China (Eurasia Daily Monitor, January 8).

The shift in relative power is particularly clear when examining China and Russia’s economic relationship. The new year appears to have begun on a good note for Sino-Russian trade relations; trade jumped in 2017, and based on third-quarter projections will rise to over $80 billion (Chinese Ministry of Commerce, November 30, 2017). Since oil exports represent the majority of Russian exports to China (52 percent in 2016), the recent uptick in previously flat oil prices is likely to further pad Russia’s export tally (OEC, 2016). Chinese and Russian cooperation in the oil sector continues to expand, with joint oil and gas pipelines snaking across China’s western and northern borders.

Chinese investment has also rescued several Russian oil and gas projects, such as the Yamal Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) plant (pictured below), which received an infusion of needed cash from China National Petroleum Corporation (Xinhua, December 27, 2017). Another project, a pipeline in northeastern China, will transport 38 billion cubic meters of natural gas from the border in Heilongjiang province across eastern China to Shanghai (Xinhua, December 13).

The Yamal LNG Plant in Sabetta, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Russia. Image courtesy of Planet Labs.

China’s winter energy crisis in 2017 and its drive to replace its coal-fired electricity generating plants with natural gas may further incentivize Chinese companies to invest in Russian oil projects (China Brief, December 22, 2017).

However, while the rise in bilateral trade might seem dramatic, it is important to keep a couple of structural factors in mind. In reality, both countries trade more with the European Union than with each other. Germany, for example, exported $85 billion to China alone in 2016 (OEC, 2016). It is also far from certain that China even needs Russian energy in a strategic capacity. Bobo Lo, an Australian expert on Sino-Russian relations has noted China has great flexibility to use the open markets and replace Russian oil and gas if need be. [1] Chinese investments throughout Central Asia mean that it has also has access to Turkmen, Tajik and Kazak natural gas pipelines (SCMP Infographic).

Sino-Russian trade has traditionally been a hedging strategy for both partners—used to make better deals with other more lucrative partners. For Russia that increasingly may no longer be the case. In December 2017, Russia used the remaining cash in its “rainy day” Reserve Fund that was meant to offset temporary budget shortfalls due to changes in the price of oil (Meduza, January 10; Russian Ministry of Finance January 10 [Russian]). With the Brent price of crude oil up around $70, Russia’s economy may benefit for the short term, but long-term trends in the price of petroleum and alternative energy sources promise oil prices far below the comfort zone of Russian companies.

The strategic calculus is changing as well. Russia could once rest easy at thought of a military confrontation with China. However, a once-ineffective and bloated Chinese military has reformed, reorganized and retrained. While the disposition of China’s troops has remained largely the same since tensions with Russia were high, the sophistication, equipment and ability of their troops have improved (China Brief, May 15, 2017).

Even China’s small but potent nuclear forces are now prioritizing penetration of advanced missile defenses in a move that has implications for Russia as well as the United States (China Brief, January 12; China Brief, April 21, 2016). In other technological domains, including quantum computing and artificial intelligence, China is poised to leave cash-strapped Russia far behind (China Brief, December 22, 2017; China Brief, December 21, 2016).

China’s rise has been profoundly disruptive for Russia across the breadth and length of Eurasia. Traditional spheres of influence have been challenged or completely supplanted.

Russian enthusiasm for Belt and Road projects that do not go through Russia, or for Chinese Arctic ambitions that avoid the Russian-controlled route, are muted (Eurasia Daily Monitor, October 3, 2017). However, Russia remains optimistic it can project power and influence into Central Asia—using infrastructure paid for by China. Even if Chinese economic growth slows, its eclipse of the Russian Federation—and memories of the Soviet Union—is complete. Russia has been consigned to being a politically useful junior partner, not an equal.

While both countries have eagerly promoted the image of Sino-Russian cooperation at a grand scale, a degree of skepticism is warranted. In the end, Moscow and Beijing’s relations are predicated on the old Maoist adage “If you don’t attack me, I won’t attack you” (人不犯我,我不犯人). Their self-interest does not make them allies.

Notes

- Lo, Bobo. A Wary Embrace: A Lowy Institute Paper: Penguin Special: What the China-Russia Relationship Means for the World. Penguin Books Ltd, 2017. Kindle edition. Location 574.