Dependency on Russia and Belarusian Identity

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 11 Issue: 9

By:

Recently published detailed analysis of Belarus’s economic problems on the Russian analytical portal Regnum (https://www.regnum.ru/news/1752886.html) is couched in stridently negative terms. The highlights include a decline of industrial exports to Russia because of lower (recession-conditioned) demand and heightened competition due to Russia’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO); the necessity to spend $3.6 billion in 2014 on servicing the existing loans; lack of progress in the area of privatization; and galloping inflation. One of the underpinnings of Belarus’s economic travails closely resembles that of the 2011 financial crisis. Namely, from January to October 2013, real (adjusted for inflation) wages rose by 17.9 percent from their level during the same period in 2012, whereas labor productivity rose only by 2.3 percent. Considering that Russia has invested $5.8 billion in Belarus’s economy and that Russia provides Belarus with low-interest loans, the Regnum report faults Belarus for “explicitly Russo-phobic actions.” In particular, the report criticizes the Minsk City Court’s December 24, 2013 rejection of the Cultural and Educational Association “The Russian World’s” request that its activity in Belarus be legalized. Regnum also rebukes Belarus for spending “billions of Belarusian rubles” on the restoration of the estates of Polish and Lithuanian nobilities and on reproducing the so-called Slutsk belts, i.e., elements of the nobility’s attire in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Such rebukes—amidst an economic narrative—cannot but be perceived as the reflections of a geopolitical struggle for Belarus’s historical memory.

Indeed, in Belarus, emphasizing the necessity to foster Belarusian identity in the face of deepening economic dependency on culturally close Russia appears to be meaningful and timely. During a January 3 televised debate on Tut.by, Belarus’s most visited internet news portal, Denis Melyantsov of the Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies reminded the audience that 70 percent of Belarusians polled in 2013 find it acceptable to merge their country into a single state with Russia if this would improve the economic situation (https://news.tut.by/politics/380939.html; see EDM April 11, 2013). He also averred that only a clear sense of identity may mobilize the society to embrace painful economic reforms. In his turn, Sergei Chaly pointed out during the debate that “we [Belarusians] have no symbols. In every country portraits are exhibited of historical personalities of political and cultural significance. But do we have at least ten of those with the potential to unify people, not divide them?” Not just opposition-minded experts, but President Alyaksandr Lukashenka himself also voiced concern about the national idea. On January 9, during a speech at the award ceremony “For Spiritual Rebirth,” he said that “the time has come to identify what will become the Belarusian idea that will unify all citizens so everyone will believe in it, from the academician to the peasant” (https://naviny.by/rubrics/politic/2014/01/10/ic_articles_112_184209/).

It may be that “the time has come” is an understatement, as developing a distinctive Belarusian identity is actually overdue. The recent appointment of the new leader (Metropolitan) of the Orthodox Christian community, the largest religious community in Belarus, is a case in point. Belarus’s Orthodox Church is not autonomous (autocephalous) but is a part of the Moscow Patriarchate. On December 25, the former leader, Filaret, retired, and the new leader, Pavel was appointed by Moscow. Just as his predecessor, Pavel (whose secular name is Georgy Ponomarev) is an ethnic Russian with no connection to Belarus and no command of the Belarusian language (https://news.tut.by/society/381311.html). His previous position was in Riazan, a regional center to the southeast of Moscow. Some critics claim that Pavel’s swift appointment contradicts article 13 of Belarus’s law “On freedom of conscience and religious organizations,” according to which only a citizen of Belarus can lead such an organization, and the solicitation of an appointment of any foreigner to the priesthood has to be directed to the Commissioner for Religious and Ethnic Affairs at least one month prior to this person’s arrival in Belarus. These legal provisions have been used to reject the appointments of the citizens of Poland as Catholic priests in Belarus and to deny extensions of their terms (https://forb.by/node/397).

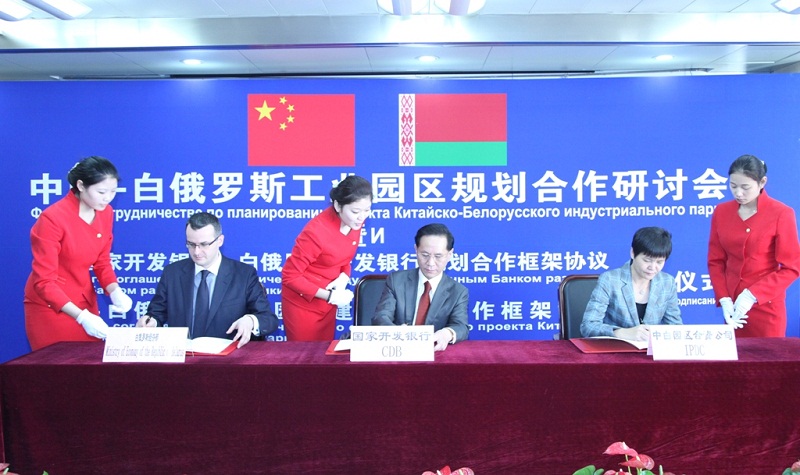

According to other experts, however, critical dependency on Russia may be offset by developing three major economic projects with roots in Belarus. Ironically, writing for a super-patriotic Russian internet journal Odnako (However), a spinoff of the eponymous propaganda show on the First Channel of Russian TV, the Belarusian author Alexei Dzermant identified three such projects (www.odnako.org/blogs/show_35752/?). First, he named the Chinese-Belarusian Industrial Park, which is being built close to the Minsk city line and next door to the international airport serving the Belarusian capital. Eight hundred hectares has been assigned to industrial buildings and 200 hectares to administrative, commercial and residential structures. The planned value of investments in this park is $30–35 billion. Sixty percent of the park’s managers are going to be citizens of China. Already the would-be park has six resident companies, three of which have been disclosed—Chinese smartphone producer ZTE as well as two pharmaceutical firms from Russia and Belarus. The profile of most of the prospective resident firms in the park is high-tech. The park is expected to make Belarus a true industrial leader in Eastern Europe (https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2380430).

The second project identified by Dzermant is the Astravets nuclear power plant, whose construction was launched in November 2013. Although funded by Russia, the project will reduce the share of natural gas (from Russia) in Belarus’s electricity generation from the current 95 percent down to 66–67 percent. The third project is the expansion of the existing Belarusian High-Technology Park, whose export of services amounted to $300 million in 2013 and is expected to reach $1 billion by 2016. According to Dzermant, these three projects not only demonstrate how to collaborate with Chinese, Russian and Western investors for the sake of Belarus but also how to become a growth pole and development driver for a large part of Eurasia.

It is not clear at the moment if the implementation of these projects will actually boost Belarus’s independence. But given a record of overcoming Belarus’s existential problems over the course of the last 20 years, the possibility of this outcome should not be discounted.