Desertification Control Drive Focuses on Food Security and Soft Power Influence

Desertification Control Drive Focuses on Food Security and Soft Power Influence

Executive Summary:

- Desertification control is central to People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) food security strategy, enabling the expansion of arable land and reducing dependence on U.S. agricultural imports amid rising geopolitical tensions.

- Xi Jinping has shifted the “Three Rural Issues” framework to prioritize grain self-sufficiency over rural economic development. These efforts underpin PRC’s push for strategic resilience, with large-scale land reclamation, soybean substitution plans, and domestic meat production advances designed to ensure food stability during potential conflicts or trade disruptions.

- Desertification success is being exported as a soft power tool, with the PRC promoting its “Chinese Solution” to ecological governance in Central Asia, Africa, and the Middle East through One Belt One Road-linked partnerships, training programs, and international forums.

On April 9, 2025, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) imposed additional tariffs on U.S. goods, including on over $26 billion in agricultural items—roughly 16 percent of total U.S. imports. This move signaled a bold step toward reducing reliance on imported staples like soybeans (Office of the Customs Tariff Commission of the State Council, April 9; Sina Finance, April 11). Historically, the PRC has been reliant on foreign imports of meat, as well as the soybeans and other grains used in the animal feed needed for domestic meat production, to feed its population. Data from 2023 shows that oilseeds and grains made up $19.5 billion or almost half of U.S. agricultural imports, while meat and poultry accounted for around $4.5 billion. Out of all oilseed and grain imports, soybeans alone made up a massive $15.6 billion in 2023 (CF News).

The PRC’s Ministry of Finance maintained the steep new 125 percent tariff rate on agricultural goods, despite exempting other items such as pharmaceuticals, microchips, aircraft engines, and ethane. This suggests an increasing comfort in decoupling from agricultural trade with the United States (CNBC, April 28). Since the early years of the Jiangxi Soviet in the 1930s, the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has stressed building food independence to “ensure the Chinese people’s rice bowl is firmly in their own hands” (确保中国人的饭碗牢牢端在自己手中). In the words of Mao Zedong—and quoted by Xi Jinping at the Central Rural Work Conference in December, 2019—“Eating is the most important thing” (吃饭是第一件大事) (CPC News, October 16, 2019). As global supply chains face new challenges and trade tensions escalate, Beijing’s drive to achieve self-sufficiency food production without relying on easily disrupted maritime imports is accelerating.

The PRC’s Road to Self-Sufficiency

Since 2022, American oilseed and grain exports to the PRC have steadily declined as the PRC government began to quietly implement three- and five-year plans explicitly designed to reduce reliance on imported foodstuffs, especially from the United States (PRC Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, December 29, 2021, April 12, 2023).

This shift is rooted in decades of agricultural modernization and innovative land reclamation efforts, all aimed at the single goal of ensuring food security. Since the early 2020s, the CCP and Xi Jinping have explicitly stated that national rural and agricultural policies are now primarily oriented toward building a domestic agricultural sector capable of feeding PRC’s massive 1.4 billion-strong population, even in the event of a major conflict or naval blockade.

National grain production exceeded 500 kilograms per capita in 2024, according to government statistics, meaning that the goal of total domestic food security has very nearly been achieved (CCTV, January 20). At current domestic production levels, PRC authorities could provide each citizen with around 1,200 calories daily from rice alone, even if a naval blockade halted all grain imports. At about 94 million tons, domestic meat production in 2024 could provide about 67 kilograms of meat per person per year, which is just below PRC’s current annual consumption rate of about 100 million tons (China Statistical Year Book 2024, accessed May 12).

Pressure points do still exist, however. For instance, domestic meat production far exceeds meat imports, but the domestic industry is heavily reliant on imported soybeans and other oil seeds to sustain it.

An Introduction to Practical Desertification Control Methods

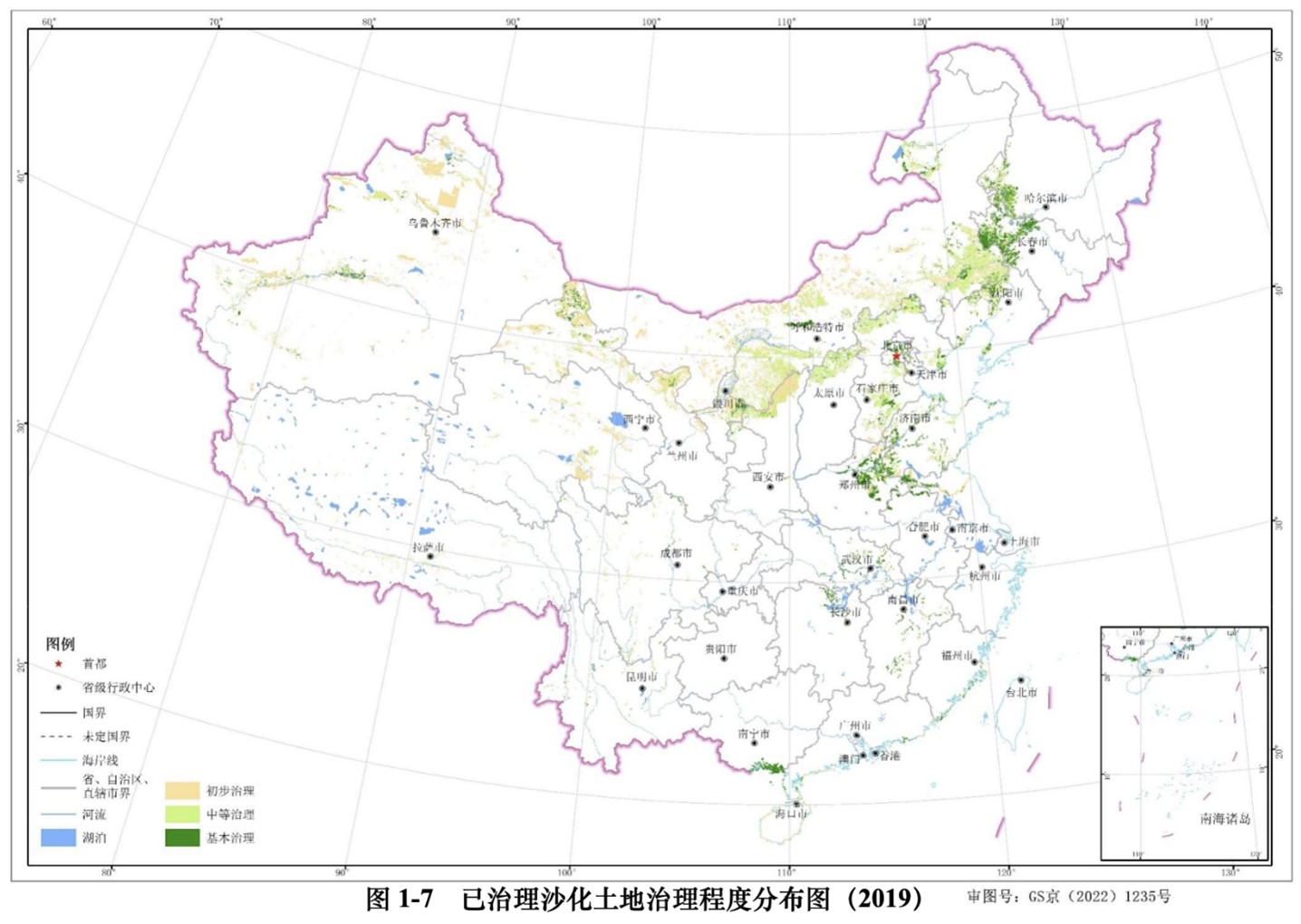

The PRC has achieved self-reliance in food production in part via a nationally prioritized program to combat desertification. Under the “Three North Shelterbelt Project” (三北防护林工程) and other programs, the PRC has now massively increased the nation’s total area of farmland through reclamation of existing deserts and the active protection of existing arable land (National Forestry and Grassland Administration, February 14).

Chinese farmers have used a method for “fixing” (风固沙) desertified sandy soil in place known as “straw checkerboarding” (草方格) since the 1950s as the primary method of countering and reversing desertification. [1] The process involves inserting stalks of straw or other dried plant material into the desertified sand in a grid pattern, with each grid typically measuring about one square meter. Once this grid pattern is in place, the area is typically planted with drought-resistant seeds or seedlings. These straw grids prevent wind erosion from shifting the sand, allowing for the formation of a layer of topsoil and, eventually, the growth of grasses and shrubs. Initially an incredibly labor-intensive technique, it has been mechanized since the early 2010s, greatly reducing the time and manpower needed for large-scale checkerboarding projects and allowing vast areas of desert in regions like Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, and Xinjiang to be processed into grasslands with topsoil that does not erode with shifting sands.

PRC scientists have also developed more technical solutions to combat desertification. Lab-cultured cyanobacteria—microorganisms capable of photosynthesis—have been deployed to augment the effectiveness of more traditional methods. Application of these cyanobacteria form biological soil crusts over sandy soil. This reduces the time needed for the development of a stable topsoil layer from 10 years to just twelve months. [2] As with many other food security-related drives, officials sanctioned the use of cyanobacteria in 2020 in Tibet, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia.

As of 2024, these efforts had resulted in the “Green Line” (绿线) in the Yellow River Basin moving 300 kilometers westward and 65 million mu (亩) (4.3 million hectares) of desertified land had been “controlled” (治理) into land with stable topsoil, according to PRC state media (People’s Daily, December 2, 2024).

In March, the PRC State Council built on these programs by implementing a plan for “Gradually Converting Permanent Basic Farmland into High-Standard Farmland” (逐步把永久基本农田建成高标准农田实施方案). This plan set out a concrete list of objectives: reaching a total of 1.4 billion mu (90 million hectares) of high-standard farmland by 2030 while also “transforming and upgrading” (改造提升) 280 million mu (19 million hectares) of degraded land into arable land. Even more ambitiously, the plan aims to have converted all “permanent basic farmland” (永久基本农田) into high-standard farmland by 2035 (Xinhua, March 30).

Desertification Control and Domestic Food Security Policy

Food security has always been a central plank of CCP governance. Since the 1920s, the Party has prioritized grain production as a symbolic and practical tool for building public support and legitimacy. It frequently publicizes successful land reclamation programs and grain production figures to domestic audiences, and Xi Jinping often mentions land reclamation efforts in speeches, stressing its links with increasing domestic food production and broader national security imperatives.

Desertification control and food security fall under the broad umbrella of the “Three Rural Issues” (三农问题), a set of priorities consistently promulgated in official publications since the early 2000s (Sina News, March 11, 2003). They issues are summarized, per the Party slogan, as “farmers are suffering; rural areas are impoverished; and agricultural industry is in danger” (农民真苦、 农村真穷 、农业真危险). They first became well-known after a letter with the same title was sent to PRC Premier Zhu Rongji (朱镕基) in 2000 by Li Changping (李昌平), a local party secretary in rural Hubei province. The letter bluntly outlined core structural weaknesses in the country’s rural and agricultural policies, and it is now frequently cited in official publications. At its core, the “Three Rural Issues” is an attempt to ensure social stability and food security in the PRC’s rapidly changing society, not just by reducing inequality between urban and rural populations via rural economic development and agricultural modernization, but by encouraging new generations of citizens to see agricultural work as a profitable and viable career, thus ensuring long-term food security.

In a speech at the fifth plenary session of the 19th Central Committee in late 2020, Xi Jinping shifted the focus of the “Three Rural Issues” from economic development to food security, in an apparent change in policy. He said that “ensuring the secure supply of important agricultural products such as grain is the top priority of the ‘Three Rural Issues’ work” (保障粮食等重要农产品供给安全,是“三农”工作头等大事), and warned that “absolute security” (绝对安全) was needed for grain provisions (Qiushi, August 31, 2022). Since 2020, this change in priorities has manifested in various directives and in the allocation of resources from economic development to food security.

Like many other rural development objectives that fall under the “Three Rural Issues” umbrella, desertification control efforts in the PRC go hand-in-hand with directives from the center. Since Xi’s 2020 speech, these directives expressly advocate for decreasing reliance on foreign agricultural imports. One example the “Three-Year Action Plan for Reducing and Substituting Soybean Meal for Feed” (饲用豆粕减量替代三年行动方案), released by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs in 2023 (MARA, April 12, 2023). This plan directs feed producers to reduce soybean meal in animal feed from 14.5 percent in 2022 to 13 percent by 2025, and to reduce national consumption of soybeans by at least 4 million tons annually, with projections for additional future reductions. Food security and supply chain stability are specifically mentioned in the text of the plan, which built on topics outlined in “document number one” from earlier that year, which focused—as it does every year—on rural issues (Xinhua, February 13, 2023).

Besides efforts to reduce soybean consumption, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs launched the Soybean and Oilseed Production Capacity Enhancement Project (大豆油料产能提升工程) in 2022. PRC-based media described the project as an effort to reduce reliance on U.S. imports, as well as the driving force behind planting an additional 27 million mu (1.9 million hectares) of soybeans that year (China Business Journal, January 3, 2023). The ministry also targeted Northeastern China and the Yangtze River Basin for the planting of new soybean and oilseed farmland. These regions have also been the focus of desertification control efforts (People’s Daily, July 12, 2022). Directives like these, alongside land reclamation efforts, have significantly reduced dependence on foreign imported staples—even for crops which the PRC has historically struggled to produce domestically in sufficient quantities to meet national demand.

Foreign Influence Operations and the ‘Chinese Solution’ for Global Ecological Governance

Beijing frequently touts its successes at home as a model worthy of emulation by countries overseas (China Brief, May 9). Its successes in combating desertification have received the same treatment. They have been promoted in foreign influence campaigns, especially in Africa and Central Asia, where events such as those hosted by the Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography and the PRC Pavilion at the United Nations Conference on Desertification aim to “tell China’s story well” (讲好中国的故事) in this domain (Xinhua, December 7, 2024). A recent initative has been the promotion of a “‘Chinese Solution’ for Global Ecological Governance” (全球生态治理“中国方案”) to foreign audiences, especially in Mongolia, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Africa (People’s Daily, June 18, 2024).

PRC government entities have engaged in several ways with other countries on desertification. These include holding exhibitions at global summits on desertification, most notably in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in December 2024; and establishing and funding permanent centers dedicated to evangelizing the “Chinese Solution” to foreign governments. Examples include the “China-Arab International Research Center for Drought, Desertification and Land Degradation” (中阿干旱、荒漠化和土地退化国际研究中心成立) opened in cooperation with the League of Arab States in August 2023, and the “China-Mongolia Cooperation Center for Combating Desertification” (中蒙荒漠化防治合作中心在乌兰巴托揭牌设立) in September 2023 (Chinese Academy of Forestry, September 9, 2023, accessed May 12). In Africa, the PRC has held multiple workshops and hosted various seminars in pursuit of cooperation in various projects, including supporting the African Union’s “Great Green Wall” project. Recent coverage has detailed the PRC’s “six-in-one” (六位一体) solution to fighting desertification in the region. One expert from the Chinese Academy of Sciences is quoted as saying that, “as a big and strong country, we have a responsibility and a duty to share our … models … This is our solemn commitment” (作为一个世界上的大国、强国,我们有责任、有义务把我们 … 模式 … 推广应用。这也是我们的一个庄重承诺) (Guancha, March 13; Chinese Academy of Forestry, accessed May 12).

PRC policy also openly links desertification control efforts to One Belt One Road projects that “serve the national strategy” (服务国家战略). The National Plan for Desertification Control and Prevention 2021-2030 (全国防沙治沙规划 (2021–2030年)) articulates an ambition to strengthen exchanges and cooperation with developing countries in desertification control to serve the national strategy. The goal of such cooperation is to “highlight the PRC’s image as a responsible major country and win wide praise from the international community” (彰显了我国负责任大国形象,赢得了国际社会的广泛赞誉) (National Forestry Bureau, December 15, 2022).

Conclusion

By transforming deserts into farmland and reducing reliance on foreign imports, the PRC has bolstered its ability to feed its 1.4 billion citizens, even amid global trade disruptions or potential conflicts. These efforts, part of broader food security work, also position the PRC as a leader in ecological governance beyond its borders—providing opportunities for advancing influence among “Global South” countries. Despite challenges posed by strained international trade relations and a historical legacy of famines, the PRC maintains robust control over its food security in 2025—all by careful and deliberate design.

Notes

[1] Li, Xiaodong [李小东]. “Study on Wind Prevention and Sand Fixation Benefits of Mechanized Straw Barriers with Different Specifications on the Southern Edge of the Tengger Desert [腾格里沙漠南缘不同规格机械化草沙障防风固沙效益研究].” Forestry Machinery & Woodworking Equipment [林业机械与木工设备] 50, no. 7 (2022): 114–119.

[2] Park, C. H., Li, X. R., Zhao, Y., Jia, R. L., and Hur, J. S. “Rapid Development of Cyanobacterial Crust in the Field for Combating Desertification.” PLOS ONE 12, no. 6 (2017): e0179903. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179903.

[3] “High Standard Farmland” (高标准农田) is defined as “arable land that is flat, concentrated and contiguous, has complete facilities, supporting farmland, fertile soil, good ecology, strong disaster resistance, and is suitable for modern agricultural production and management methods. It can ensure high and stable yields in drought and flood” (土地平整、集中连片、设施完善、农田配套、土壤肥沃、生态良好、抗灾能力强,与现代农业生产和经营方式相适应的旱涝保收、高产稳产) (Department of Nature Resources of Hubei Province, November 8, 2020). “Permanent Basic Farmland” is unoccupied arable land designated for agricultural use, whether or not it is currently being farmed (Department of Nature Resources of Hubei Province, December 30, 2019).